In the aftermath of the 2015 World Cup, there was significant focus on attacking strategy and the northern hemisphere's failings in this area. A similar conversion is coming down the tracks.

Over the past four years, teams have evolved and reacted to attacking evolution with improved defensive structures. Renowned coaches like Andy Farrell, Jacques Nienaber, Shaun Edwards and John Mitchell have brought remarkable line speed and resolute discipline to their sides in a bid to shut down and stifle opposition attack.

There has been developments in attack as well. One of them has been the increasing popularity of the 1-3-3-1 attack shape. The British and Irish Lions used it in 2017 and it is widespread in the southern hemisphere.

During this tournament, Ireland have also continued to adopt this shape while Japan have implemented an efficient variation.

But what exactly is the 1-3-3-1 attacking shape and what are the differences between Ireland's iteration and the Japanese one?

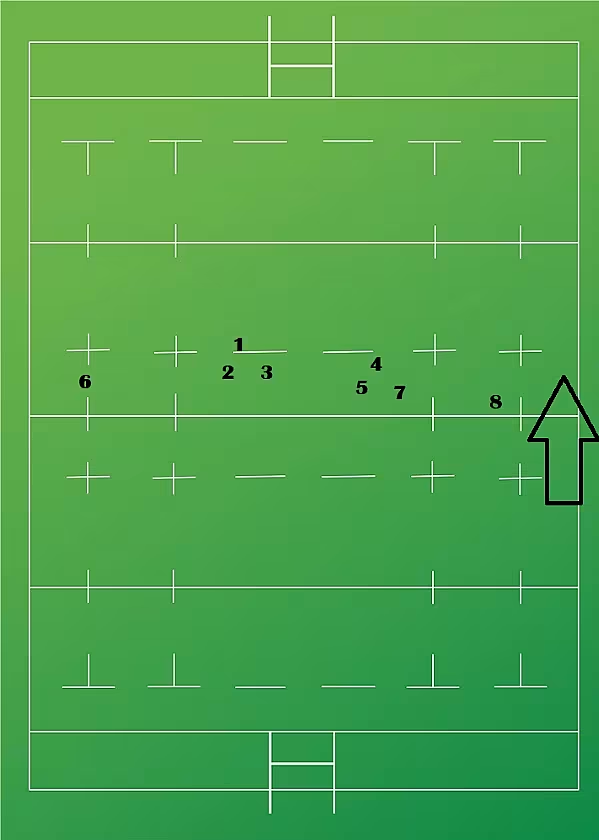

1-3-3-1 is an attack formation from open play. Teams will generally organise their forwards into a 2-4-2 or 1-3-3-1 formation with their backline behind them while in possession.

The goal is to manipulate a defence by creating a mismatch or space. Slight variations can fix defenders or make it easier to spread the ball wide. Below is an illustration. Naturally, in practice, it rarely reflects exactly this with players committed to rucks or play fragmented.

The key to Ireland's gameplan under Joe Schmidt is control. Therefore, they set up in this shape, keep it tight and take few risks. They have powerful ball carriers like CJ Stander, James Ryan and Tadhg Furlong so they utilise them. Accuracy and a low-error count are paramount.

Ireland play between the two 15 metre lines. At their robust and bludgeoning best, they grind teams down by coming over and back across the field.

Defence is draining. They aim to capitalise on that by controlling possession and creating a mismatch. The ideal is as follows.

Ireland start with a ruck and pass to a forward in the middle of a pod of three. The forward hits up and they repeat this until they run out of space and come back again.

Every carry is a wrestle for the gain line and matched with a clinical cleanout. They continue to come over and back. The defender makes the tackle but has to work to get back in the line. Because of Ireland's shape, their forwards just need to get up and back into the structure, ready for another carry.

By the third or fourth ask, the defence is tiring and becoming less structured. Suddenly players like CJ Stander or Tadhg Furlong are running at backs or fatigued tacklers. This strategy forces tries or penalties.

Japan have a pack weight of 875kg, 21kg lighter than Ireland and no player over 6'5. There's is a game not suited to close quarter contact so they set-up with a much broader shape, more of a 1-3-2-2.

Their Tony Brown crafted attack does the simple extremely well. It relies on speed and their skill-set rather than penetration and power.

Basically, Japan ask their opposition several different questions. Ireland ask their opposition the same question over and over again.

This is why when Ireland look good, they look great. Big, powerful ball carriers literally running over defenders and breaking the gain line. When they look poor they look awful because their biggest players are being stopped dead and driven back.

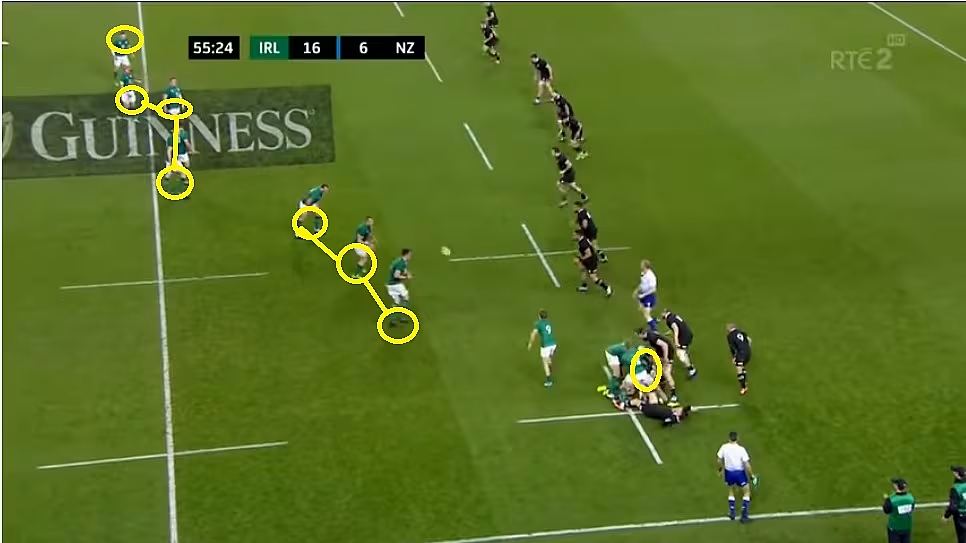

The second try against Samoa illustrates the advantage of this style and what this team does well.

It starts with an Ireland lineout and typical maul option.

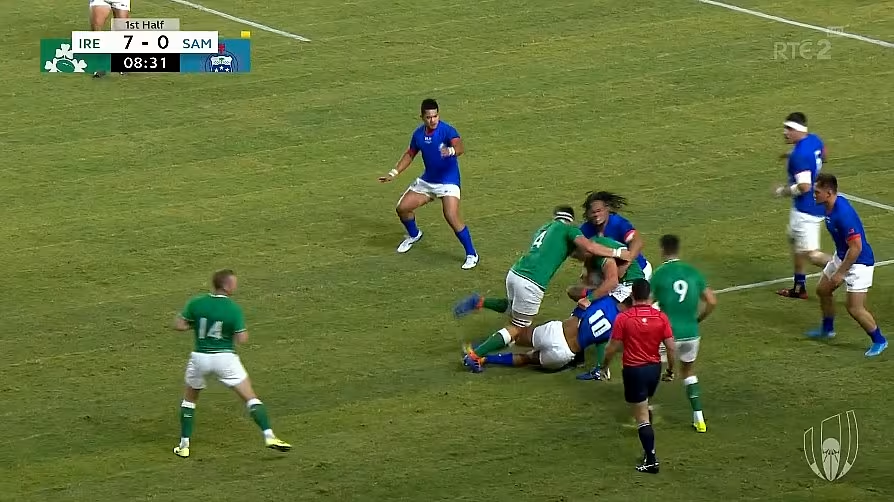

CJ Stander makes a straight-up carry and sucks in three defenders.

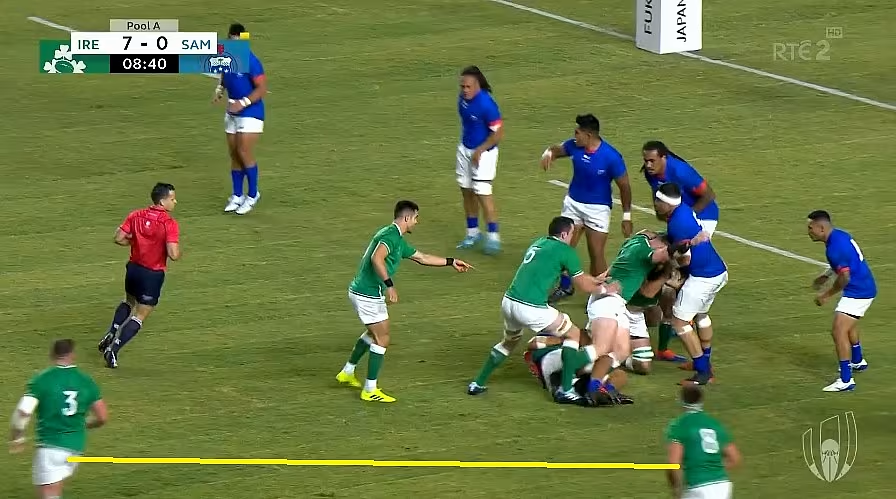

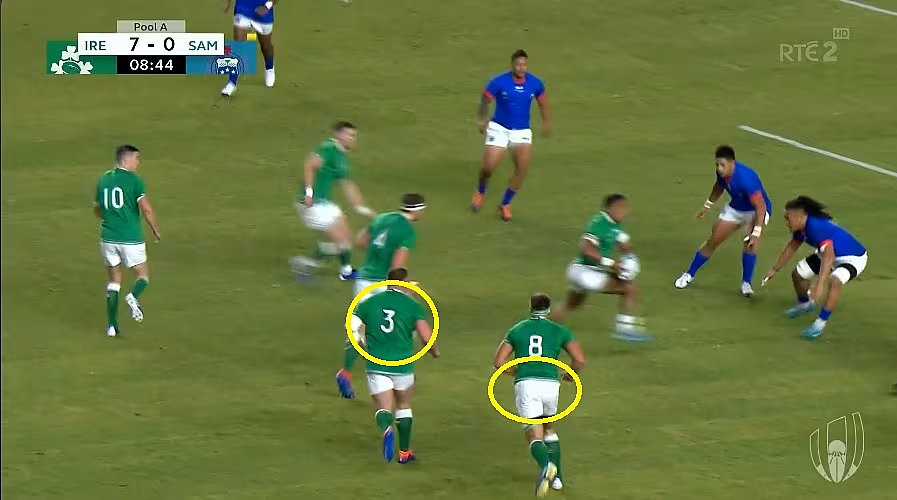

Tadhg Beirne is at the front of the pod and makes the next carry. Once again, the Irish attacker fights to make it a wrestle. Note Ireland's best two ball carriers, Furlong and Best, do not clear out the ruck but come on the loop.

Bundee Aki makes a hard carry after a good line.

Now Ireland have orchestrated a scenario with their best carriers facing soft shoulders and a centre. Furlong fires through and touches down.

Ireland 47-5 Samoa: Tadhg Furlong barrelled past a number of would-be tacklers for Ireland’s second try. pic.twitter.com/F0XL8cWZPs

— RTÉ Rugby (@RTErugby) October 12, 2019

The pod are there to punch holes. In contrast, Japan use their pod to spread it wide. From there, they can deliver their own knock-out blow as they demonstrated on Sunday.

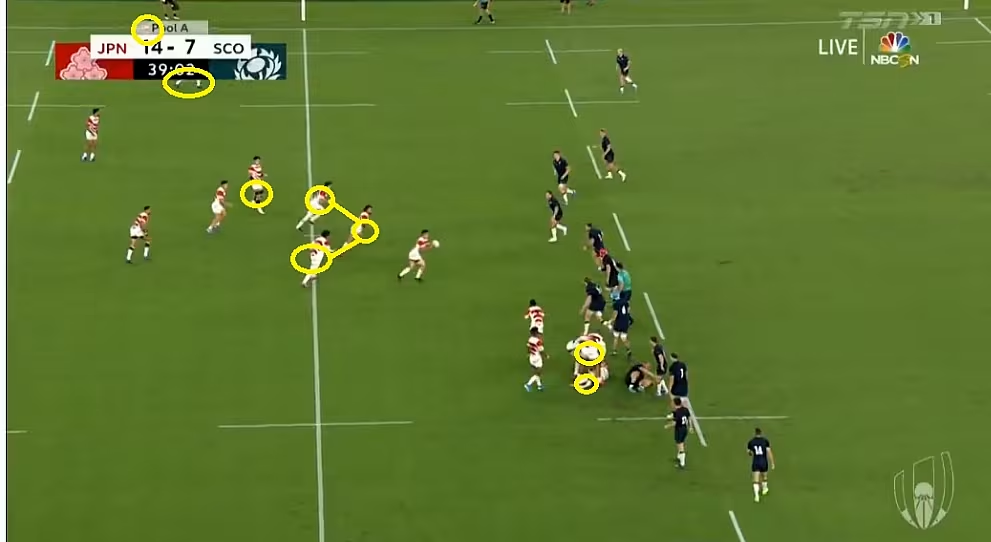

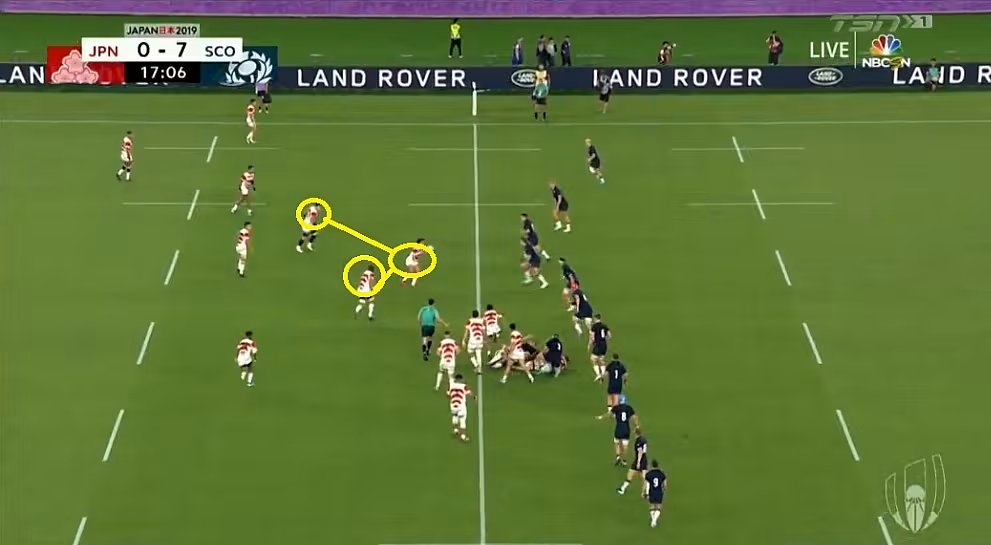

Here, Japan have perfect pod formation facing Scotland's defence.

Notice just before this, Jiwoon Koo held his hands up as if to receive the ball. Joe Schmidt is big on 'animation' with players not involved in the move needing to fix defenders and it is clear Jamie Joseph agrees with him.

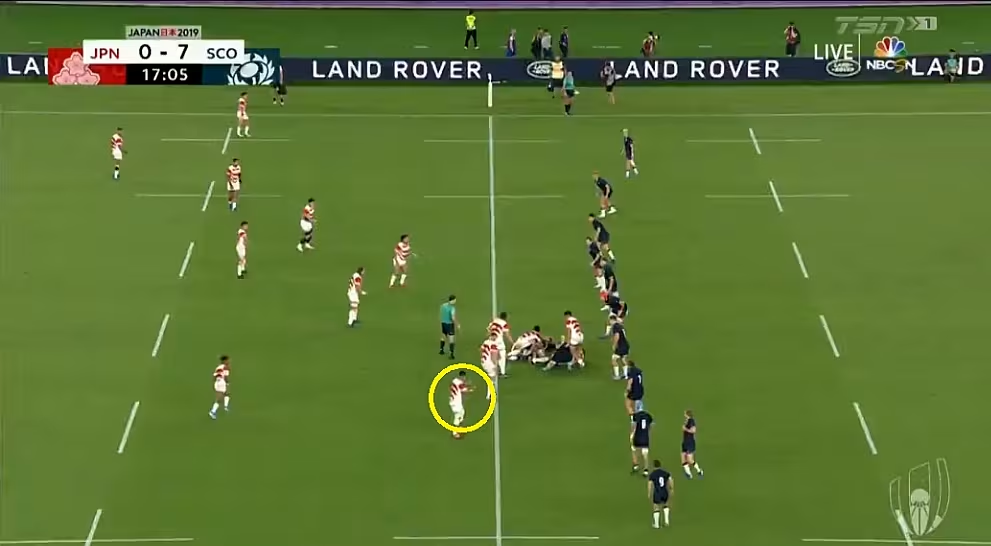

Unlike Ireland, the pod are expected to interlink and move the ball. They do so while engaging the defensive line and allow Japan to move the ball wide.

Two phases later, Matsushima scores a sensational try.

18: TRY Japan!

What an offload ?

What a try ?

That man Kotaro Matsushima again. LIVE now on eir sport 1! #RWC2019 #JPNvSCO pic.twitter.com/nzzb8nSkL3

— eir Sport (@eirSport) October 13, 2019

There is a lesson here for Schmidt's side. Their method is sound and has steered them well overall but the pack does not have to be the stick all the time, they can be the carrot as well.

Japan use their forwards as a way to get the ball wide. Like Ireland, much of this is reliant on their outhalf.

Yu Tumora literally points and tells his forwards where to run even when they are not receiving the ball. Their job is to fix inside defenders as the ball sweeps towards the edge.

It is not necessarily the case that one system is better than the other. There are many teams without the skill-set, fitness and familiarity with the conditions necessary to play like Japan. Ireland having a coaching ticket conscious of the need to keep defences guessing and the players capable of doing so.

With New Zealand looming large, it will take a perfect combination of accuracy and creativity to overcome this colossal challenge.