Since last night, many have argued that the Atlanta Falcons 4th quarter performance last night represented one of the biggest bottle jobs in all of sport. This argument has been made convincingly here.

We asked the question on Twitter today. What are the other contenders for the biggest bottle-job in sports history? We got plenty of responses, some very compelling indeed.

@ballsdotie Hillary for president

— Michael Carmody (@m_carmody) February 6, 2017

Here are the other contenders for the accolade.

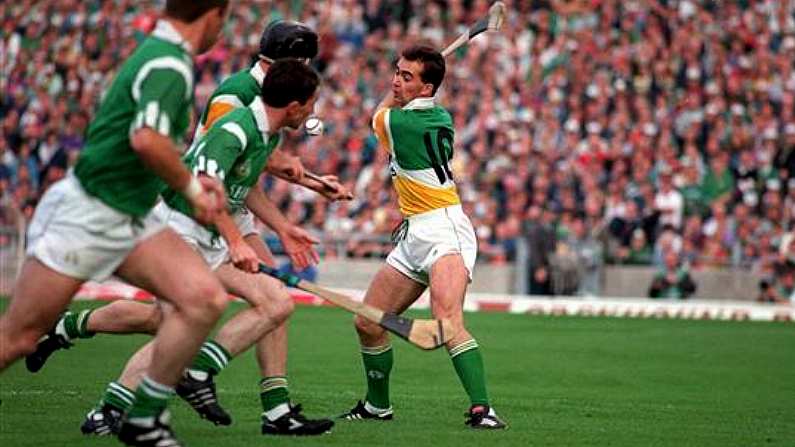

1994 All-Ireland hurling final

Limerick's star player in their 1973 All-Ireland triumph was managing Offaly in 1994. Eamonn Cregan looked confused and semi-traumatised at the final whistle.

See the above Ray McManus snap in which one Limerick supporter flashes Cregan a "what are you after doing ya cunchya" look. Poor Cregan wasn't going to look the man in the eye.

In the first flush of victory, managers don't usually so haggard and weatherbeaten. Witness Cyril Farrell being hoisted high by jubilant supporters, like a Fianna Fáil TD who had just passed the quota.

Cregan would have been conflicted whatever the result that day. But the manner of Offaly win/Limerick's loss would have generated a fair degree of inner turmoil.

Limerick played all the hurling in the first 65 minutes. With the game winding down, they led a dreary match on a score of 2-13 to 1-11. Their supporters were mentally preparing themselves for the celebration that would accompany a first All-Ireland title in 21 years.

They'd owed their comeback to the most famous acts of insubordination of hurling's golden era. Billy Dooley was brought down 21 yards from goal and his brother Johnny stood over the free. He turned around to the sideline for instruction. Quite logically, he was advised to pop it over the bar and shave a point off Limerick's lead.

Johnny decided to totally ignore this instruction. And to the surprise of everyone present, especially, it seems, the Limerick defenders massed on the line, he arrowed a low fizzing shot into the net. From the next attack, the ball was horsed straight back into the Offaly forward line. The Limerick backs missed it and Pat O'Connor pulled on the ball, whipping it into the corner.

Somehow, Offaly led by a point. Limerick offered no response. Clearly shell-shocked, they stood around like traffic cones as Billy Dooley proceeded to treat the final few minutes as shooting practice. In a surreal display, the middle Dooley child blasted over four straight points from play. A five-point deficit was turned into a six-point victory in no time.

1996 US Masters

Greg Norman, the No. 1 golfer on the planet for much of the early 90s, was also a byword for cocking up tournaments on the final day. If golf tournaments were three days long, he'd be up there with Jack Nicklaus. As it is, he's only a couple of British Open's to his name.

In 1986, Norman achieved the famous 'Saturday Slam', or the 'Norman Slam' as it has been re-named in some circles. Amazingly, he led all four majors at the conclusion of the third round that year. The British Open was the only competition he carried off.

In the 1986 PGA, he was on the green on the 18th while his rival Bob Tway left himself a treacherous bunker shot. Tway holed out and Norman was stunned.

At the very next tournament in Augusta in '87, Norman found himself in a similar position. He got himself into a playoff with unheralded Augusta native, Larry Mize, not a man used to the business end of major tournaments. On the second playoff hole at 11, Mize messed up his second shot and found himself in the dreaded hollow area to the right of the green. Norman, meanwhile, landed safely the green with his approach.

As the commentators muttered gloomily about the impossibility of Mize's position, Norman must have assumed the green jacket was his. If Mize pitched the ball too hard, it could easily roll into the water at the other side of the green.

Mize holed out with his chip and proceeded to leap around like a maniac. Norman missed his tricky putt and another one slipped by.

None of these early near misses were classic chokes. But it's easy to see how fatalism could have seeped into Norman's soul. By the time we reach 1996, Norman has several more disasters under his belt.

He did win the British Open at Sandwich in 1993 but he also achieved the feat of becoming the first player to lose playoffs in all four majors.

Even the Norman's standards, he put himself in a marvelous position on Saturday night at the '96 tournament. He hit a course record 63 on the first day. He extended his lead on subsequent days. A 69 on Friday left four shots clear of the field. He managed a 71 on Saturday and led by six shots. The worrying news was that Nick Faldo was the closest behind him, a player renowned for grim pragmatism and mental solidity.

His lead was still 4 shots heading to the 9th hole. His approach shot was famously on the low side of the green, and slid down 30 yards towards the fairway again. He now led by two shots heading into the back 9. He followed with a bogey at 10. After his inexplicable three-putt on 11, he was now level with Faldo on -9.

On 12, he found the water and the gallery wailed and moaned in distress. On 13, he nearly chipped in and fell on the ground as the ball shaved the hole. Two shots behind on 16, he hit a horrible tee shot and landed in the water, effectively ending his chances.

1993 Wimbledon Ladies Final

Wimbledon has often been described as 'sport for people who don't like sport' (by Marina Hyde in the Guardian, among others). There aren't many sports which end with the losing finalist crying on the shoulder of the Duchess of Kent. The whole scene copper-fastened tennis's reputation as the chosen sport of high-society types and soap opera lovers.

The 1993 Wimbeldon Ladies' Final featured Steffi Graf and Jana Novotna. Monica Seles might have made it but she'd been out of action since being stabbed by a German 'lathe operator' called Gunter Parche at a tournament in Hamburg in April. Mr. Parche's stated objective was to allow Steffi Graf to retain No. 1 in the world rankings.

Graf, who'd been playing second fiddle to Seles for most of 1991 and 1992, duly reclaimed the No. 1 spot and, by February 1994, held all four Grand Slams in her possession.

The 1993 French Open, the 1993 US Open, and the 1994 Australian Open, she won with a minimum of fuss. However, Wimbledon she seemed destined to lose.

Deep in the 3rd set, she unexpectedly found herself 4-1 down against the 8th seed, the Czech serve and volley specialist. Novotna had just taken the second set 6-1. Now, in the 3rd, she was serving to make it 5-1 and at one stage led 40-30.

This was the high-point of Novotna's day. It was then that fate tapped her on the shoulder and spelled out what was happening. That was the cue for a momentum shift.

At 40-30 up, she threw in a jarring double fault. On the next point, she hit a volley miles out. She nearly hit the back wall. On Graf's break point, the German sent up a lob and Novotna smashed the ball into the net.

She didn't win another game. It was one of the transparent bottle jobs in professional sport.

Serving at 4-3, Novotna hit three double faults in a single game. Graf naturally noticed what was happening and was classically German about the whole thing. She drew strength from her opponent's fraying nerves and did everything possible to exacerbate them.

At the end, the good Duchess tried to cheer Novotna up with the thought that she'd be back next year. This had the opposite effect. Novotna burst into tears and wept on her new friend's shoulder.

Graf was never one to scream booya in a vanquished opponent's face and wore a pained expression through most of the aftermath.

I was very happy in the first few seconds after winning the match. And then I saw her. I’ve been there. All players have been there, and I really felt for her

1999 Open Championship

Golfers are notoriously vulnerable to bottle-jobs. There's so much time for negative thoughts to seep in even after they've addressed the ball.

No wonder they're all on the phone to sports psychologists every few minutes. For many big names, head doctors are a critical part of their entourage.

Most golfers stumble over their first major. Once they've reached the promised land, subsequent Claret Jugs and green jackets tend to come easier.

Padraig Harrington fell over the line against another nervous wreck in Sergio Garcia in Carnoustie in 2007. The following year, he was the coolest man in England when he overhauled Greg Norman in Birkdale.

One golfer who got one chance at a Major and never got near another one was France's Jean Van de Velde. One of the curious aspects about this 'choke' was that it was not caused by excessive cautiousness on the part of the choker.

On a controversially difficult layout at Carnoustie, Van de Velde was +3 but still led by three strokes from Paul Lawrie and Justin Leonard.

Unfortunately, Van de Velde played the 72nd hold like a man who had watched Tin Cup too many times.

In a bizarre show of cavalier impetuosity, Van de Velde decided to take driver off the tee on 18. He was either determined to finish with a flourish or he was subconsciously aware of the psychological dangers of excessive caution.

Whatever the thinking, Peter Alliss wasn't on board. "I'm not sure this is right," he said ominously.

After fortuitously avoiding the water, he pulled his second right, cracking it off the wall of the Granstand. It bounced about 40 yards backwards and found himself in deep rough.

It was the 3rd shot when it was clear he was in the shit. He duffed it and it landed in the stream. Alliss spent the next few minutes pleading with him not to hit his shot from the water. Van de Velde had whipped off his shoes and socks and stood poised over the ball for a few minutes.

Even in his then mental state, this shot was adjudged too barmy for Van de Velde to try. He took a drop stroke and now needed to get down in two strokes to win. Unfortunately, his chip from 80 years didn't clear the greenside bunker. There was a serious danger he would miss even the playoff.

Ironically, he displayed good mental strength to claim a spot in playoff, nailing a five foot putt to keep his hopes alive. How did we get to that point?

1994 World Snooker Final

Tough on Jimmy White as this match was nip and tuck throughout the 35 frames. But in the 35th and deciding frame, White was in among the balls with the chance of a clearance.

Players with a history of losing finals are vulnerable to negative thoughts. White lost his first World Final to Steve Davis in 1984. But it was in the early 90s that he really hit his stride in this area.

He lost five finals in a row between 1990 and 1994. Four of them, he lost to Stephen Hendry, the other to John Parrot (1991).

Tragically, the closest he came was unquestionably the final appearance in 1994. At 17 apiece, he was at the table with the balls well placed for a frame-winning break.

37-24 ahead, he missed a black off its spot. The partisan Crucible audience, hungry for a fairytale, gasped and moaned. "Well, did he see the title there?" observed Clive Everton.

White admitted afterwards that he suffered a "severe twitch" on the fatal black.

Hendry returned to the table and cleared up, with one pink bobbling off the jaws.

"He's beginning to annoy me," White said in his post-match interview.