The landing gear jolted as the wheels connected with the runway, it amplified the noise while the breaks pulsed through the airplane and after a few seconds it had come to a shuddering halt. The heart that would save the life of a six-year-old was safely on board.

Moments earlier Cian Norris and his father had just arrived on a plane from Casement Aerodrome, they had given up all hope but a three-year wait was almost over while their window was about to shut.

Gavin Norris had lost his career and given up any semblance of normality, desperately searching for answers and a heart that would keep Cian alive. Everything now depended on surgery at Great Ormond Street Hospital.

“A donor heart needs to be from the donor to the recipient in four hours for it to be viable,” said Norris.

“For the whole time that we waited on the transplant list my phone was never turned off. We had a bag packed at the door for three years and then Cian’s nurse Helene rang and told me there was a donor: ‘Great Ormond are going to call you, get ready, there is an ambulance on the way’.

“We had spent years waiting for this call, I completely panicked and I didn’t know where my passport or anything was. The ambulance arrived and Great Ormond called me. They had to offer and you have to accept it. The ambulance took us to Baldonnell where the aircorp had the plane ready.”

That was June 2020 and Cian had deteriorated rapidly, his father was initially told he had one or two years to live, heart failure was the prognosis.

He had been a typical healthy three-year-old, Cian was born in the Egyptian capital of Cairo but his father hailed from the South Dublin suburb of Perrystown.

Norris was an oil and gas consultant and he travelled the world, and while they spent a couple of years between the UK and Malaysia, the idea was always to return to Ireland before Cian started school.

In September 2017, Cian had relocated to Dublin and was attending creche in Rathgar, his father was working in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta.

“I woke up to missed calls. It was about 6am before I realised my phone was ringing. Cian had been taken to the hospital,” said Norris.

He had a swollen liver and on initial examination, it seemed as though he could have been suffering from hepatitis but as the minutes turned into hours it was clear that this was life-threatening.

“I knew something was wrong,” said Norris.

My mother explained that they were doing some scans, they thought it was his liver, they had taken blood tests. My stomach sank and I just got dressed, jumped into the cab and went to the airport.

I booked a flight on the way and because it is two big eight-hour flights I had to get on a plane before I knew anything more. It was during the second flight, they did another test and throughout the course of the night and the next day they understood the problem was not with his liver, it was with his heart.

I had a video call on the second flight with the cardiologist explaining to me that Cian had heart failure and he needed a transplant.

It didn’t make sense at all.

Norris’ world quickly spiralled while the experts in the Crumlin Cardiac Centre struggled to find answers and give his son a fighting chance.

Even when they sent the results of the subsequent MRI, angiogram and other heart pressure tests to Great Ormond Street, they needed to be verified.

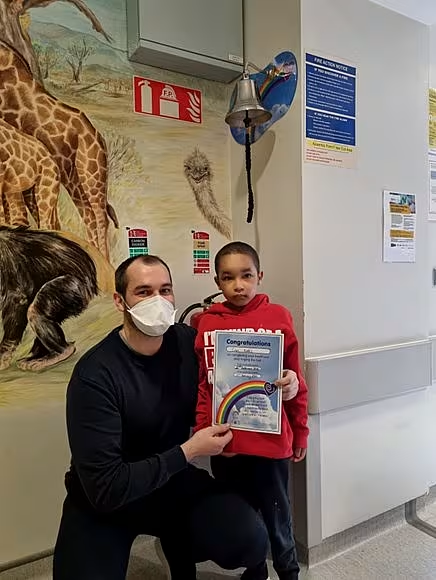

Cian Norris was delighted to receive an Irish jersey signed by Katie McCabe and the rest of the Irish Women’s World Cup squad.

“It’s called Restrictive Cardiopathy which is extremely rare, one in a million,” said Norris.

“He had to go over to London, then after that we were told Cian would have maybe a year or two to live. He would need a heart transplant immediately.”

Norris was in shock, his son now faced into an uncertain future, the terminal diagnosis was unfathomable.

Prof Damien Kenny, the leading paediatric cardiologist in Ireland, explained that he had only seen this once before in two decades of experience.

“I spent the first two weeks crying at night. You are saying, why me, why Cian, what has he done to deserve this? A beautiful child, happy and smiling and all of a sudden he has been given a death sentence,” said Norris.

“After two weeks I snapped out of it and said give me the facts, give me all the information I can get and I am going to make sure my son has the best chance fighting whatever this is. Since then I haven’t let it get the better of me.”

Being a single parent meant Norris had to shoulder the responsibility, he internalised what he learned and kept it from his own parents, who tried to help in any way they could.

His support network also included the hospitals as well as Heart Children Ireland, while the main nurse, Helene Murchan, helped to keep Cian alive during the darkest times.

Norris had spent 15 years building a successful career but he had other priorities now and placed all of his focus behind Cian.

Cian had returned to school at Bishop Shanahan National School where he had a Special Needs Assistant to guide him through the day, while they waited for a call that wouldn’t come.

There was only so much Norris could do too and by June 2020 the outlook was grim.

“It was obvious that Cian had months left, maybe weeks,” said Norris.

“They talked about a Berlin Heart, sort of a bridge. It doesn’t work for every child but it was a last option.

“And then Covid happened. The UK transplant services in adults stopped. Great Ormond Street decided to continue their transplant services because it wasn’t affecting children.

“In a strange bit of luck, the donor hearts that went to the adults went to children that were suitable. There was a flood of donations towards children with cardiac heart failure.

“It helped Cian get a transplant.”

Cian’s heart came from a teenage boy between the age of ten and 20 and that would have gone to an adult in different circumstances.

But for once luck was on their side and they travelled to England expecting to soon return to some sense of normality.

“Cian was in surgery for 11 hours. When he came back into the ICU I could tell straight away things weren’t going well. There was a team of about 15 working on him,” said Norris.

“I was told not to leave the ICU so I stayed. For the next 24 hours we weren’t sure if Cian was going to make it. Then he stabilised but normal transplant kids spend about a week in the ICU, Cian spent over 61 days.”

Cian didn’t wake up during the first week and suffered end organ failure, his organs weren’t working so his body was unable to clear the medications from his system.

He also had a bleed on his brain but finally woke up after the second week, although he continued to have organ failure.

Cian had wires coming through his chest, a machine to help maintain his heartbeat, there were machines breathing for him and cleaning his blood. There were up to 15 different lines going into his body.

“His body plumbing had to rewire, the valves into his heart, his lungs, his liver, they all matched his old heart. They didn’t match his new heart that was working perfectly. His body didn’t change overnight,” said Norris.

“You live waiting for this heart transplant that is going to save the day but you quickly figure out this is a different life you are living now.”

Cian began to recover and left hospital in a wheelchair, not able to walk as he continued to suffer the side effects of the surgery and being immunosuppressed. He was susceptible to infection.

By February 2021 Cian had returned to school but only for a few hours each day and he soon began to complain of stomach pains. He was diagnosed as having phantom pain and it wasn’t until August that they found the source.

“He had an intussusception, when one piece of your bowel goes inside another and gets trapped,” said Norris.

“He had to have emergency surgery and they cut this piece out of his belly. When they removed it they found a polyp. They were able to quickly diagnose then that he had post-transplant lymphoma.

“That’s a cancer that occurs because you are immunosuppressed. After surgery he was left with a bag, all the waste went into a bag in his stomach.”

Norris spent from August to February last year undergoing strong chemotherapy during which he spent over 80 days being infused with morphine and opioids. His system almost became resistant to the medication.

He went back to school from February but the chemotherapy caught up with him and he suffered from adrenal insufficiency. His adrenal glands stopped working so he had to take cortisol therapy.

However, there was finally some light on the horizon and after they reversed his ileostomy, Cian has gone from strength to strength since September 2022.

He returned to school and is living a relatively normal life, while his physicians continue to monitor his heart. His future won’t be taken for granted and he and his father appreciate the simple things in life now.

Cian Norris attempting a tricky putt at the Golf Ireland Inclusion Camp.

Cian has followed in his father’s footsteps and taken up golf, and with the guidance of Gary Shaw in Naas, backed by the Golf Ireland Inclusion programme he can now make a trip around a golf course and play a sport he loves.

His battle with his health continues but the bond with his father is unbreakable.

“He has put on a lot of weight and stretched since he had the surgery to reattach his bowel,” said Norris.

“He got a bike off Santa for Christmas so he started to cycle. His heart is not perfect so he still has limitations. Football might not be the sport for Cian but golf is definitely not out of reach.

“When we play golf together we get a buggy. He would manage a hole but then he will have a rest. He needs the buggy to get around.

“I approached Golf Ireland and asked if they could do anything and they said about the inclusivity camps they were running with Gary.

“It's strange because there is lots of different children there that go through lots of different things. Even the last session, I was chatting to one of the fathers. Even though the journey is different, the children get along and it’s great but even the side chats, their hopes for their children used to be, 'oh I would love my child to be sporty' and that but your expectations change.

“We see our child ride a bike for the first time and that is a huge deal for us. It’s nice to share stories like that. Cian got on great with everybody. It’s a nice environment to be able to play in. The ambition isn’t to be the best or win, it’s to have fun and enjoy yourself, that’s what it is all about.

“We wanted to give Cian this quality of life for as long as we can and it’s perfect for him.”