(This article originally appeared on Balls.ie on November 1)

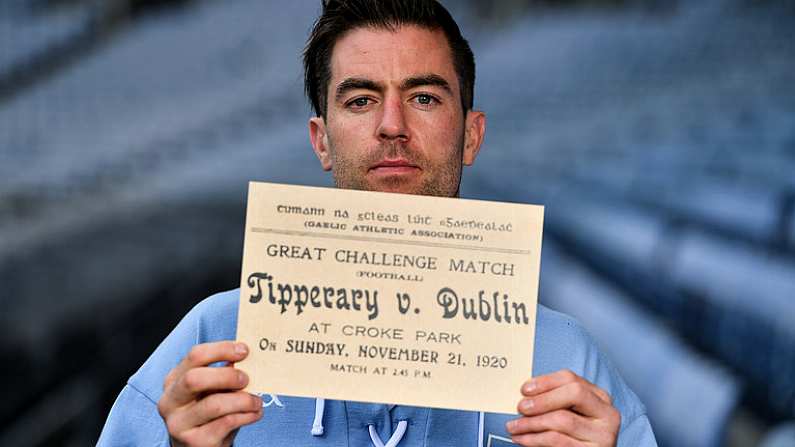

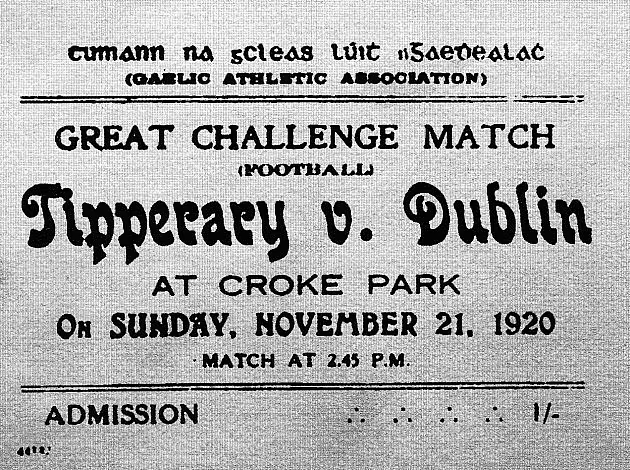

It is exactly one hundred years to the day that fourteen people were killed by British military forces at a gaelic football match between Dublin and Tipperary at Croke Park.

For an event that has taken on a mythical status in Irish sporting consciousness, it is strange that for so long, so little was known about the fourteen people who perished on Bloody Sunday. Most GAA fans will be able to tell you that Michael Hogan, who was representing Tipperary that day, was amongst the dead. For awhile, it was enough to know just that about Bloody Sunday.

But what of those other lives taken as a reprisal for the murder of British intelligence officers in Dublin earlier that day? Two children. A woman about to be married. A veteran of the British army, to name just four.

Croke Park today stands like a fortress over Dublin’s northeast inner city, so it can be hard to fathom. Fourteen people died at Croke Park on Bloody Sunday. Their names were James Burke, Jane Boyle, Daniel Carroll, Michael Feery, Michael Hogan, Tom Hogan, James Matthews, Patrick O’Dowd, Jerome O’Leary, Perry Robinson, Tom Ryan, John William Scott, James Teehan and Joseph Traynor. Eight of their bodies were interred in unmarked graves. Why did that happen and why were those names forgotten?

Asking that question gets one closer to what might the real tragedy of Bloody Sunday: not only that those fourteen people were killed by British forces, but that we almost allowed their names and stories to slip away.

For almost a decade, Michael Foley, a sports journalist with the Sunday Times, has been immersed in Bloody Sunday. His book The Bloodied Field (O’Brien Press, 2014) rekindled a popular interest in what happened in Dublin on that violent November day. Unexpectedly, it also helped kickstart a long overdue process of healing for both the families of the deceased and the GAA itself.

You can experience Foley's work on Bloody Sunday in a range of media this month. A revised and extended edition of The Bloodied Field was released earlier this year. Foley contributed to a TV documentary on Bloody Sunday that will be aired on RTÉ the week of the centenary. And, most interestingly, in conjunction with the GAA, Foley and his brother Andrew, who is a musician, have produced an intense eight-part podcast series telling the whole story of Bloody Sunday. They began recording it last November. Four episodes are currently online. It is a riveting piece of historical storytelling that stands alone from the book of the same name.

GAA fans will be hearing a lot about Bloody Sunday over the next few weeks. It's been fascinating to see how proactive the GAA have been in trying in engaging the families of the deceased in order to reshape the legacy of Bloody Sunday. The centrepiece of this is The Graves Project, which sought to provide tombstones for those victims in unmarked graves. Obviously covid restrictions will greatly alter the GAA’s plans to mark this solemn occasion. Yet right in the middle of this strangest of GAA championships, with Croke Park’s stands empty and silent, it could be the perfect time to look back and try to understand anew Bloody Sunday. At the heart of it is the effort to remember these fourteen lives that were lost and almost forgotten.

Balls.ie caught up with Michael Foley last week to discuss his new podcast and why Bloody Sunday still matters, 100 years on.

DM: Can you talk to us a bit about your journey with Bloody Sunday after The Bloodied Field was published?

MF: When the first book came out in 2014, I didn’t want to do a launch. I just wanted to put it out there. It did whatever it did. [During the research process] families and relatives of the people who died were very hard to find. Most of the stories had been lost in the first place.

Once the book came out then, it just started to evolve. The real catalyst was the Unmarked Graves project. In 2015, the family of Jane Boyle (who was shot and killed that day, five days before her wedding) was in the process of erecting a gravestone for her and we got in contact and through that, we got the GAA involved, and the GAA started the Unmarked Graves project.

He kneeled down next to a dying Michael Hogan, on the pitch in Croke Park, and whispered a prayer into his ear. For this Thomas Ryan lost his own life.#B100dySunday - https://t.co/0YyrIyygwQ pic.twitter.com/QH3xoKIlbF

— The GAA (@officialgaa) October 23, 2020

So through that, I met loads of family members, and suddenly those family members took on a life of their own. Suddenly they became real. Up to this morning, literally this morning, I got a text from a Bloody Sunday relative saying ‘we finally found out where our family member was from’. One of the lads I’m working with on the TV documentary found a photo of one of the kids who was killed that I’d never seen before. I saw it last night.

I realised into 2015 and 2016 that there wasn’t a month that would go by without someone getting in touch about the book, either to say they enjoyed it, or someone asking about the victims, or someone offering info on an artifact. So it’s never gone away. I’ve been doing this for nine years and it’s never gone away.

DM: Why was so little known about the victims of Bloody Sunday?

MF: The graves are always a good place to start. They’re the victims. Whenever those people were buried, they were told no shows of strength, no flags, no speeches. Only close friends and family were allowed. It was a little bit like now. Meanwhile, the people who were killed in the morning were given state funerals. Westminster Abbey, Westminster Cathedral, all that. From the very beginning, you had this downplaying of what had happened.

Some of those families wanted to put up gravestones in their own time. They were afraid of reprisals from the Black and Tans and the British authorities.

At the time, the GAA never really dealt with it. There weren’t a lot of expressions of condolences in the minutes of meetings straight after 1920. And okay, they named the Hogan Stand after Michael Hogan, and there was an annual game every year between Tipp and Dublin all the way up to the 1970s. But I think the GAA never really knew how to access Bloody Sunday. They never really knew how to process it, as an organisation. There may be reasons for that. There were a lot of politics attached to the GAA in terms of Northern Ireland going back through the years. Their status didn’t really allow them to step back. It’s only in the 21st century that they’re allowed to take a step back and be seen not only as a games-based organisation, but as a community-based organisation.

It’s almost like, if you’re talking about it in human terms, it’s almost like someone suffering PTSD and not being able to handle something for years and years, until some combination of situations allows them to unlock something that they haven’t been able to access for a very long time, and when they do - and I can’t speak for the GAA - but I think they found it cathartic. The grave unveilings I’ve gone to, the conversations I’ve had with people in the GAA, I think as an organisation, they’ve found it cathartic and liberating that they’ve been able to go back and establish these links.

DM: Talk to us about The Bloodied Field podcast and why you chose this format for retelling the story?

MF: It’s a bit like eating. You engage the subject with your senses. If you’re reading it, you’re engaged with your imagination to form a picture in your head. With a podcast, depending on the music and your delivery and the way you emphasise certain things, you can paint a different picture and maybe a more vivid one.

I just thought the book has had a good life. There’s an updated version out. People are reading it. There’s been a fantastic reaction to it down the years. I thought the podcast was a different way to get the story to people who wouldn’t be inclined to read the book. It’s an accessible way into it.

The updated version of the book is 85,000-90,000 words, with the updated chapter. The scripts are around 35,000 words! So you’re telling the story in a very different way. You have to. You can’t just read the book. You have to distill it down.

You also have the Abbey doing 14 plays on the 14 victims. There’s the two-part TV documentary for RTÉ that’ll be aired the week of the centenary. There’s a lot of ways into this story now.

21 November 2018; A general view of the memorial headstone to Bloody Sunday victim John William Scott who was shot and killed aged 14 at Croke Park which was revealed today at Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. Photo by David Fitzgerald/Sportsfile

DM: How do you expect the GAA to honour Bloody Sunday in three weeks time? [note - Foley serves on the GAA’s History Committee]

MF: There’s always been a conviction to do something. What shapes it takes, how it looks, that’s all dependent on how many people you can get into a particular place and time. The big focus is that it’s on the people, the victims. Whatever shape the commemoration takes, it will be focused entirely on the victims, and trying to understand and appreciate Bloody Sunday through the eyes of these people.

DM: Can you tell us about the responsibility that you now feel to the Bloody Sunday families through this project and the closeness you feel to them?

MF: I’m always wary about how I explain my feelings about the Bloody Sunday victims. They’re the ones who lost loved ones. The relatives now wouldn’t have known the people who would have died but they would have known aunts and uncles of the victims, and they would have carried around sadness for those people. In the case of the unmarked graves, they would have seen the upset it would have caused an aunt or uncle that a family member would be in an unmarked grave.

I feel a real pressure to get it right. I’d feel a connection to the victims so that as many people as possible hear their story and understand, without being pushy about it. If people want it, it’s there.

“Will you tell my da I’m hurt?”

William was just 11 years old, shot as he sat in a tree watching the match.

100 years on, we remember him.#B100dySunday pic.twitter.com/Zc3ALTi3Cp— The GAA (@officialgaa) October 29, 2020

At the graves unveiling in 2019, twelve of fourteen families were there. And the reason it was only twelve of fourteen is that two of the family lines - of the two kids, John William Scott and Jerome O’Leary - had run out. The other two families had someone to speak about who the victim was. But Jerome had no one. I got a call from Cian [Murphy, from the GAA press office, who has played a massive role in driving the GAA's involvement in Bloody Sunday] and asked to confirm his name and address for the gravestone. It was a small thing, and I got thinking about it, and realised it was part of the process you do for someone when they die.

MIchael Foley speaking just before a grave unveiling at Glasnevin Cemetery in 2019

The GAA were great and they had a wreath there. They made the point that he had no family but the GAA were his family now. Even just for me to confirm that little bit of info for his grave and to say a couple of words so he wouldn't be left alone or left out of it. It was one of those things in my life that I was asked to do that I won’t forget.

Download The Bloodied Field podcast on all good podcast providers.