Three things everybody knows about the GAA...

Biddy Early had it in for the hurlers of Clare and Galway

The second most famous herbalist in the GAA after Sean Boylan.

Received wisdom has it that Biddy Early was a one woman curse machine, who appeared to devote most of her 74 years on this earth to sabotaging nearby sports teams.

In GAA lore, she appears as a malevolent figure, with the ability to impart losing thoughts in the heads of hurlers born years after her death, like a kind of reverse Enda McNulty.

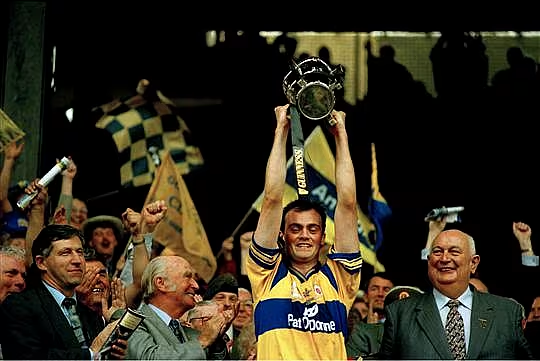

When Clare finally lifted the Liam McCarthy Cup in 1995, Ger Canning made a point of sticking it to Biddy in his commentary. Almost pointing at the sky and saying take that you bitch.

Biddy Early, a Clare woman, apparently placed curses on the hurlers of Galway and Clare, both of whom suffered long droughts in the middle of the 20th century.

It's fair to say that planting a curse of this nature would have required an astonishing degree of foresight on Biddy's part, not least because she died in 1875, nine years before the foundation of the GAA.

In an Irish Times interview in 2011, Billy Loughnane, the owner of her cottage, thoroughly demolished the curse story.

She is fondly remembered locally, nationally and internationally as an extraordinary woman who devoted her time to comforting and healing the sick.

She is not known ever to have cursed anyone. She experienced some difficulty with one local clergyman of the day who, for reasons of his own, labelled her a ‘witch’.”

He said Early had been accused of putting a curse on the Clare hurling team, saying they would never win an All-Ireland. Mr Loughnane has dismissed this for many years as “rubbish”.

That Edward Carson played hurling at Trinity College

Historians, both professional and amateur, are fond of making the assertion that the father of Irish unionism played hurling at Trinity College.

Edward Carson, Dubliner and lawyer extraordinaire, founded the Ulster Unionist party in 1912.

Politicians of many persuasions are in thrall to this titbit, using it to highlight the wonderful diversity and complexity of Irish identity. In 2010, when Gerry Adams organised the inaugural 'Poc ar an Cnoc' (Puck on the hill) on the green in Stormont, he proposed that the trophy handed out to the winners be named after Edward Carson.

It is true that Edward Carson did play a ball and stick team sport while at Trinity College.

But it wasn't hurling.

No, the sport Carson played at university was called 'hurley' - a game which resembled hockey more than it did hurling and was invented by English public schoolboys*, not Irish nationalists.

*Rather confusingly, what the rest of the world might term 'private fee-paying schools' are known in England as 'public schools'.

In fact, hurley players regarded hurling with contempt, characterising it as 'the swiping game of the savage'.

In Carson's case, the GAA hadn't even been invented when he attended Trinity College.

UCD historian Paul Rouse has been to the fore in debunking the myth that Carson could have the been the nineteenth century Liam Rushe, if only blasted politics hadn't intervened.

The difference is there was no game of hurling played in Dublin in the 1870s - there was instead a game in Trinity College called hurley which was most likely brought across by English public schools and organised by Trinity from probably 1869 to the 1880s.

Hurley was less physical than hurling and was played entirely on the ground. It was played by the Dublin protestant community, of which Carson was very much part.

That 1974 was the first time Dublin people had ever heard of Gaelic football

To all intents and purposes, it seems that to the people of Dublin, Kevin Heffernan invented Gaelic football in 1974. It was the first time Dublin had ever competed properly with a team of actual Dubs representing them and not a bunch of country fellas who just happened to live in the place.

But this is not true. 19 years before, Hill 16 was covered in blue as Dublin faced Kerry in 1955 All-Ireland final - with a team comprised wholly of lads born in Dublin.

And it goes back further. In his brilliant book on Bloody Sunday 1920, Michael Foley writes of how Dublin were exactly as they are now, with the same glamour attached, the same unpopularity outside the Pale and the same controversy about getting to play all their games at Croke Park.

The Dubs did experience a renaissance in 1974 but it is by no means the first time that Gaelic football had flowered in the capital. Perhaps, it's truer to say that they were the first exceptional Dublin team of the television era.