A version of this article originally appeared on Eoin Keane's website Bold Thady Quill.

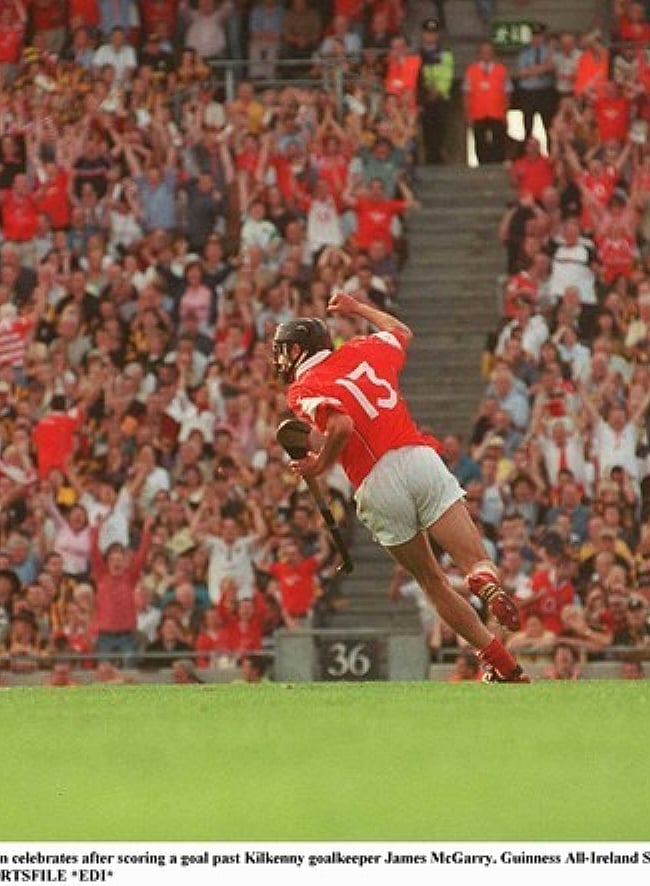

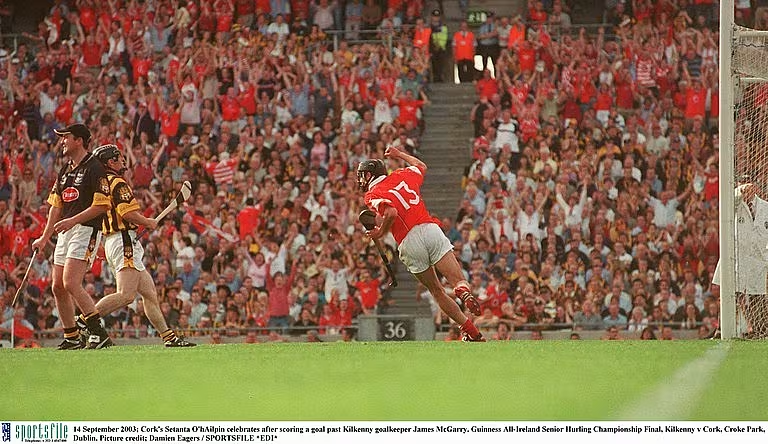

Fifty-three minutes had elapsed in the 2003 All-Ireland final when Setanta converged on a loose ball just inside the opposition D, before swatting Noel Hickey aside and rifling the ball past James McGarry in the Kilkenny net. A game that had failed to deliver even the slightest of sparks, had suddenly ignited. A game that, for the best part of an hour, had seen Cork’s attack malfunction to scarcely believable proportions even twenty years on, was now level. “Santa Claus has delivered Ger”, yelped an excitable Cyril Farrell. Santy always did deliver. And excitable yelps generally followed. But if ever a sporting career could be summed up in one moment, it was that one – an all too fleeting moment of exaltation and expectation, brutally and abruptly usurped by the forlorn dreams of what could have been.

Cork lost, Setanta left and the light that burned twice as bright, didn’t burn for half as long as we’d all hoped.

While the 2004 campaign will, for obvious reasons, be remembered fondly for its final destination, the preceding year remains etched in the collective memory of Cork hurling supporters for its journey; five games stretched out across three months that saw a vibrant, young Cork team emerge from the winter of discontent that had gone before. And there was none younger or more vibrant than the brother of Sean Óg, boasting a name plucked from The Táin that, even before a ball was thrown in that summer, exuded connotations of magic and otherworldliness.

Even before Setanta, The O’hAilpín story was one of legend; how the family swapped an antipodean idyl for the recessionary gloom of Cork’s northside in the late ‘80’s and how Sean Óg’s immersion into the fabled hurling academies of Na Piarsaigh and North Mon saw nurture overcome nature’s restraints to mould him into an All-Ireland winner. It was always thought that Setanta would become one too. “Pound for pound, he is the best product of the family”, claimed Sean Óg in an interview many moons ago. It wouldn’t take long for that expectation to spread from the family home in Blarney to the four corners of the county and beyond.

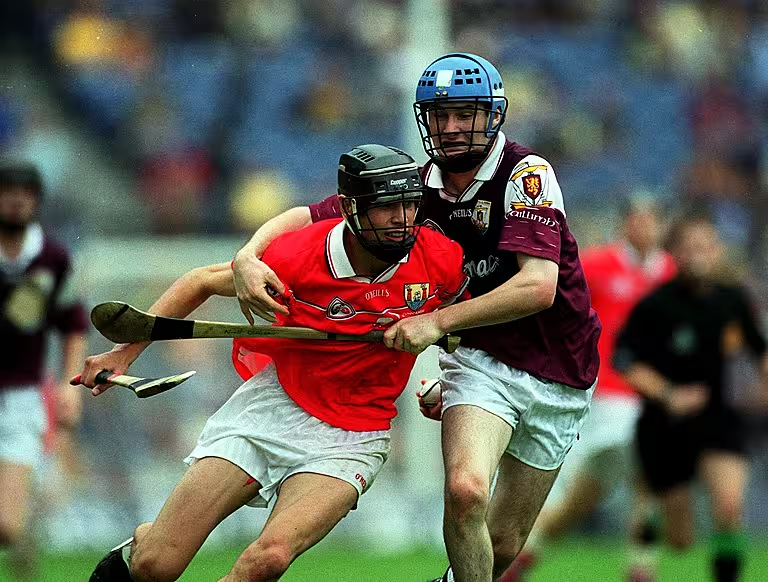

A goal and a point in the All-Ireland minor final defeat to Galway in 2000 certainly gave credence to the belief that Setanta could emulate, or even surpass, the feats of his older brother. And by the time Cork’s ill-fated 2002 season came around, Setanta was on the fringes of involvement. Not that he was an unfamiliar face around the team prior to that. Ever since Sean Óg’s breakthrough with Cork in the mid-90’s, his younger brother had been on the outer-most periphery of the team, the honour of pucking ball out from behind the goal afforded to him when he’d thumb a lift into Cork training from Blarney. When he was finally invited to join in the fray on the other side of the posts, he didn’t waste time in demonstrating what he was all about.

10 September 2000; Cork's Setanta Ó hAilpín in action against Niall Corcoran of Galway during the All-Ireland Minor Hurling Championship Final between Cork and Galway at Croke Park in Dublin. Photo by Ray McManus/Sportsfile

READ ALSO: GAA Fixtures: The Weekend's Big Gaelic Football And Hurling Games, And How To Watch Them

“There were trial games and Setanta would clean up” remarked Sean Óg in that same interview. “He was cleaning up in A versus B matches and I remember one match and all the players were saying he definitely has to play”. Bertie Óg Murphy remained unconvinced and when he requested that Setanta perform the vital role of hurley-carrier for a qualifier clash with Galway, Setanta thought that his talents be best utilised stateside. So, as the Cork senior hurlers entered into a nadir through an insipid nine-point defeat above in Thurles, Setanta was hurling in the green and white of Limerick, footballing in the green and gold of Kerry, and labouring in the dust and sweat of a Bronx construction site.

Setanta emerges

When Setanta finally got his chance under new management, he wasted no time in taking it. After a couple of impressive displays in the early rounds of the 2003 National League, the Na Piarsaigh man made his first start in late April against All-Ireland champions Kilkenny, and more intimately against All-Star full-back Philip Larkin. While a solitary point from play reflected unkindly on his display, the calling ashore of Larkin with twenty minutes of the game left to play bore a more reliable reflection on his performance. “On a day when DJ Carey confirmed yet again his greatness, perhaps the most outstanding single fact to emerge from yesterday’s game in Páirc Uí Chaoimh was that Setanta Ó hAilpín has confirmed his own growing stature in the game”, wrote Diarmuid O’Flynn of the Irish Examiner. The Dodger himself was equally fulsome in his praise.

“I’ve been looking forward to seeing Setanta making the step up to senior level for a few years now and he did it today. He’s a fine prospect.”

Correlations between DJ and Setanta, players for whom surnames were rendered obsolete, are worth exploring. Since the turn of the millennium, a relaxation of rules surrounding player endorsements had seen some of the game’s most eminent players benefit from an influx of commercial sponsorship. Many, including Carey, who had been one of the earliest and most successful in his expeditions of these uncharted waters, proceeded to fill their boots – both literally and figuratively. That summer, six prominent intercounty players, Carey included, broke new ground in signing lucrative deals with Puma to the tune of a reported €2,000 each. And it was into this arena that Setanta came hurtling.

An oven-ready poster boy, Setanta showcased a magnetism of style and appearance (remember those Del Piero side burns) and a name lifted from Irish mythology that not even the savviest of PR gurus could have bettered. With DJ, the GAA’s first real superstar, on the wane, his natural heir in the commercial realm was apparent. This was two years before the Guinness’ ‘Stuff of Legend’ ad campaign that saw the story of CúChulainn brought to life. That same year, the fledgling sports channel that shared its name with Cork’s prodigy got it’s first slice of the GAA pie, with rights to host evening national league games. It doesn’t take much imagination to wonder what the advertising suits could have made of our boy wonder.

Certainly, the old game had ceased to be, both on the field and off. If players’ extra-curricular dealings put paid to any romantic notions of the GAA as an amateur organisation in the strictest of guises, the ructions in Cork throughout the winter of ’02 brought to a close the perception of players behaving, and being treated as amateurs. Due in no small part to the strike and the concessions that were to follow, the Cork team that lined out to play Clare in the opening round of the Munster Championship was arguably the best-prepared in the history of the GAA.

Rebirth of the Rebels

Setanta was one of only three debutants named to kickstart Cork’s rebirth – not quite the revolving door that normally signals revival, as it had done four years prior to that in 1999 when Jimmy Barry-Murphy so bravely infused the side with six greenhorns. The entire team, however, were entering into a championship campaign for the first time as elite athletes. They had asked and fought for that privilege and under O’Grady, they had been treated as such. As Clare soon found out, they were more than willing to walk the walk in the heat of battle too.

That game returned Cork to the conversation. It also encapsulated Setanta in all his multi-faceted glory. It is worth noting that at this juncture that ‘O’Gradyball’ was still in its infancy, its intricacies not yet hard-wired into the consciousness of a group of players that had known nothing but the helter-skelter of 90s hurling. With Tom Kenny plying his trade at half-back and Jerry O’Connor biding his time on the bench, the twin-turbo engine room that would come to power Cork’s running game had yet to be unleashed. As such, the long ball to the corner was still the ruse de guerre.

With this in mind, Setanta’s gangly 6ft 5inch frame was draped in the number 13 jersey. In the weeks leading up to the game, Diarmuid O’Sullivan had primed Setanta for the physical challenge that the Clare corner-back, Frank Lohan would undoubtedly pose. After only eight minutes, Setanta proved the value of that schooling. A high ball came in from Sherlock and Setanta claimed it over his marker, knocking the Clare captain onto his arse. It was the start of a long day for Lohan.

8 June 2003; Setanta O'hAilpin, Cork, in action against Clare's Frank Lohan. Guinness Munster Senior Hurling Championship Semi-final, Clare v Cork, Semple Stadium, Thurles, Co Tipperary. Picture credit; Pat Murphy / SPORTSFILE *EDI*

Over the course of seventy-four minutes, Setanta produced a display that showcased everything that he could bring to the table. He scored three points from play, one at a vital point in the game when Clare had reduced the deficit between the teams from nine to four. With every point scored or free won, he proceeded to jump around like a wild bull that refused to be tamed. He harangued Lohan to such an extent that a coming-to between the pair should have seen the Wolfe Tones man sidelined for a wild pull. He fist-pumped and grabbed his crest and drew energy from the ebullient Cork crowd. And them from him. That electrifying symbiosis would carry like a wave through the summer. With ten minutes left in the game, The Banks were in full flow. Cork were back. And a new hero was in tow.

And all stars need a tagline. As the story goes, Setanta had returned from his American sojourn the previous summer in time for Na Piarsaigh’s U-21 championship decider against their three-in-a-row chasing neighbours, Glen Rovers. When a club official opined that their young buck might take it handy on his hapless defensive colleagues and opt instead to knock a couple over the bar, Setanta offered the classic retort “I don’t do points”. Apocryphal as do it may be, the perfectly crafted quip was certainly worthy of Cork’s all-action hero. Setanta did, of course, do points, as his haul versus Clare did attest. But if there was even the slightest whiff of a goal, you could rest assured that Setanta would follow that trail with reckless abandon. And points be damned.

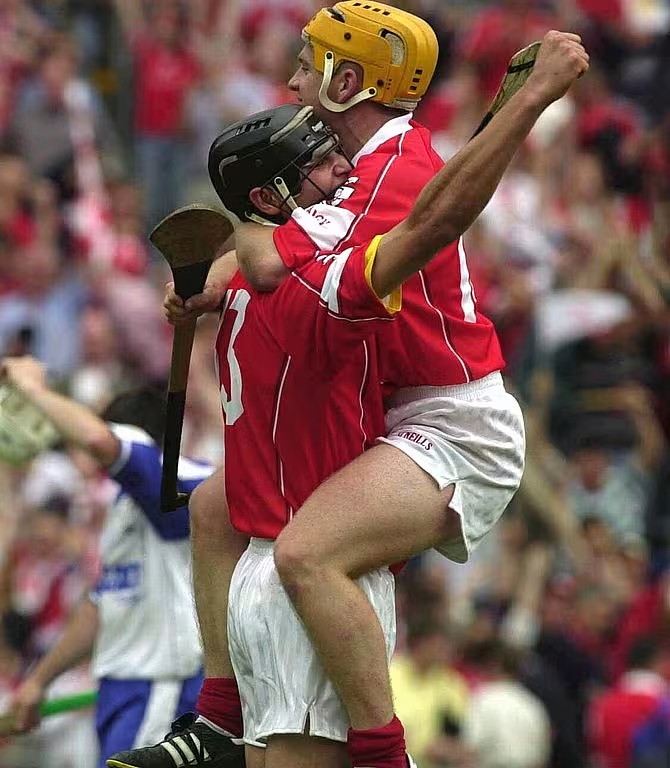

Six-minutes into the Munster Final, Setanta picked up the scent from Niall McCarthy’s mishit shot, pouncing onto the ball in front of the Waterford goalkeeper, Stephen Brenner. Cork had yet to score and from the tightest of angles and facing the corner-flag, a point would have more than sufficed. Not a chance. I don’t do points. Later in the game, a white flag again seemed like the most economical of options when Setanta gained possession around the middle of the field. Instead, he made a beeline for goal, forcing a goal opportunity from which Alan Browne duly obliged. Cork won by four and Setantamania went into overdrive.

29 June 2003; Setanta O'hAilpin, left, Cork, celebrates with team-mate Joe Deane at the end of the game after victory over Waterford. Guinness Munster Senior Hurling Championship Final, Cork v Waterford, Semple Stadium, Thurles, Co. Tipperary. Picture credit; David Maher / SPORTSFILE *EDI*mirro

Setanta’s presence in the 2003 championship season was a tidal wave of star quality and player adoration not seen since the days of JBM”, recalled Mick Finn in an interview with Cork hurling historian, Tim Horgan. “Young schoolchildren in and around the city and, indeed, the county were hurling and fighting over the naming rights to Setanta. There was an aura that fans couldn’t get enough of”. With Munster conquered, the hordes hit the road for Croke Park. On a sweltering August afternoon, Cork and Wexford played out a frenetic encounter that twisted and turned in front of 60,000 sun-drenched supporters. And the main attraction didn’t disappoint.

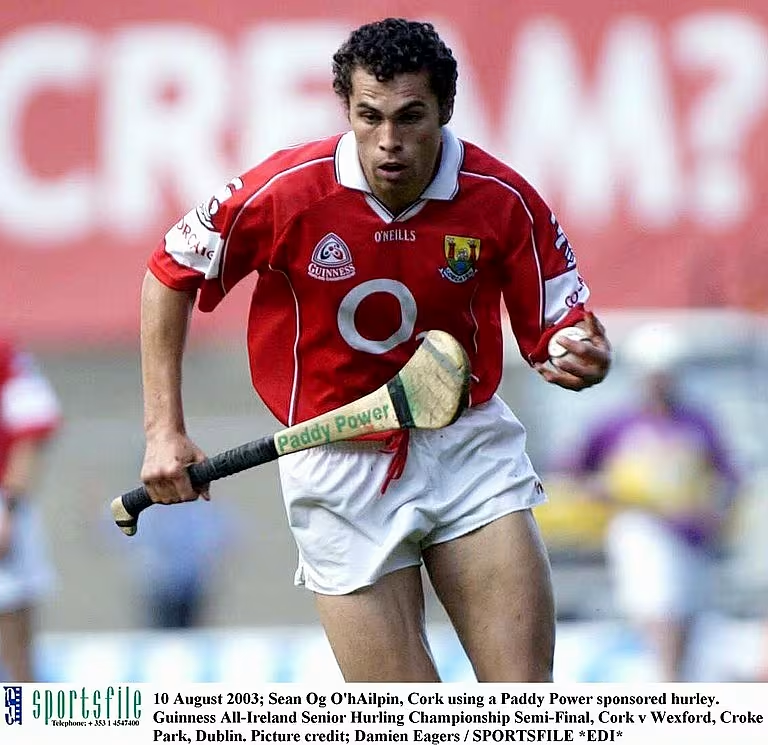

That game may be remembered for its chaotic beauty but it is also remembered for the saga that brought to the forefront the financial incentives that had steadily become open to players. It was the game where Wexford’s Damien Fitzhenry and Paul Codd, along with Cork’s Sean Óg O’hÁilpín took to the field carrying hurleys garlanded with Paddy Power logos, each player receiving an estimated €750 for the privilege. The selection of players chosen was evidently based on which sticks would garner the most TV exposure – Fitzhenry’s puckouts, Codd’s free-taking and Sean Óg’s sidelines.

10 August 2003; Sean Og O'hAilpin of Cork using a Paddy Power sponsored hurley during the Guinness All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Semi-Final meatch between Cork and Wexford at Croke Park in Dublin. Photo by Damien Eagers/Sportsfile

But the golden boy of hurling was also in the crosshairs of the marketing men. A representative from the bookmaking firm came calling to the O’hAilpín household on the weekend prior to the Wexford game, tasked with collecting the hurleys for branding. Setanta, however, was busying himself down the Páirc in the Munster U21 final against Tipperary. Naturally, he had his best sticks with him. And so, the murky affair that once again saw the contentious topic of player endorsement placed front and centre of GAA news cycles did so without the organisation’s most marketable asset. In any case, Setanta’s foremost contribution to the game occurred without the aid of his unblazoned wand.

Wexford started with a purple patch and a golden streak to open up an early six-point lead. There was still four points between the teams ten minutes into the second half when Dairmuid O’Sullivan sent a long, hopeful free down onto the Wexford goalmouth. Up rose Setanta and down came the ball. Moments later, the ball was in the net, courtesy of a side footed effort that, while lacking the panache of Nicky English ‘87, possessed the same ingenuity of which only the mavericks are capable. That goal finally stoked something in Cork and ten minutes later they were five points clear. We all know how it ended, Rory McCarthy’s late late goal earning a replay and solidifying the game in the annals of history as an all-time classic. In the replay, Cork made no mistake and Wexford were duly dispatched.

A star is born

In his autobiography, Sean Óg recounts how everybody wanted a piece of Setanta:

“The demands on Setanta’s time were threatening to get out of hand. The Celtic Tiger was beginning to roll and businesses had some money for marketing, and Setanta was getting phone calls morning. noon and night”.

Eventually, the team’s statistician Eddie O’Donnell, a Tipp man exiled in Mallow, was doubling-jobbing as Setanta’s agent, looking after his diary as the bookings came in thick and fast. The lost earnings from the Paddy Power fiasco soon proved to be small change. The following week, Setanta was named as one of ten intercounty players chosen by drinks company Cantrell & Cochrane (Club Energise to me and you) as part of an ambitious marketing campaign that saw billboards spring up around the country, with each player receiving €2,250 for their image rights.

But for Cork supporters, the residing image of Setanta remains that of him wheeling away from goal in that year’s decider, kissing the crest and performing that iconic salutation where he flapped his arms as if to say to all ‘Calm down, I’ve got this.’ We’d little reason to doubt him either. In truth, it was probably Setanta’s quietest games of the summer, although he hardly lacked for company on that metric. Certainly, it wasn’t the final act befitting the protagonist of Cork’s resurrection.

The story arc did, however, follow a similar trajectory to another of Na Piarsaigh’s most heralded sons. In 1982, a nineteen year old Tony O’Sullivan emerged as one of the most exciting attacking prospects in the country as he ripped up the Munster Championship in his debut season. Kilkenny bettered them in the final however and Tony Sull was subbed off late in the game. Of course, he went on to win three Celtic Crosses and five All-Stars. As it was with ‘the Baby Jesus’, All-Ireland final defeat at the beginning of Setanta’s career was meant to be exactly that. The beginning.

It is espoused I’m sure in some quarters that Setanta O’hAilpín failed to fulfil his potential; that by choosing the path less travelled, he exchanged what would surely have been a decade long residency as a hurling icon for a life of relative anonymity as an Australian Rules player. The truth however, when viewed outside the prism of our national games, is that nothing in Setanta’s life in the GAA became him like the leaving it. He amassed 88 appearances over ten years in the AFL, a total surpassed by only five players from these shores in the history of the Irish experiment with the oval ball down under.

In doing so, he forged a career as a professional athlete, a lifelong ambition that despite the increasingly lucrative opportunities available to the GAA’s prized stars, would not have been possible if he stayed in Cork, scoring goals for fun – and for free. In an interview with Dermot Crowe earlier in the year, Donal O’Grady revealed that “there were moves afoot to sort him out with some position in Cork that would allow him kind of act as a professional, to play when he wanted”. With this in mind, perhaps his departure for Australia served the greater good, his legacy left untarnished by the complications of money and the trapping of fame in the fishbowl of Irish sporting life.

14 September 2003; Cork's Setanta O'hAilpin celebrates after scoring a goal past Kilkenny goalkeeper James McGarry. Guinness All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship Final, Kilkenny v Cork, Croke Park, Dublin. Picture credit; Damien Eagers / SPORTSFILE

And we got our All-Ireland in the end. With another tacked on for good measure. It is, of course, quite possible that the three-in-a-row could have been achieved with a full-forward line of Deane, Corcoran and Setanta but to engage in such thoughts would be to show scant regard for the vagaries of sport. Who honestly knows what would have happened had Setanta stayed? Hurling is littered with examples of players who failed to live up to the impossibly high standards they set for themselves, while no number of goals was ever going to suppress the internal wranglings that resurfaced in what would have been the prime of his career.

In the opening round of the club championship prior to his emergence as a household name, Setanta bagged three goals and seven points for Na Piarsaigh in a rout against Douglas. His performance led to locals bestowing him with the nickname ‘Setanta 3:7’, a nod of course to Limerick supporter and Christian evangelist Frank Hogan’s famous biblical signage. Not many could have predicted then that 3-7 would be the final tally accrued by Setanta in the red of Cork when all was said and done in September. And nobody could have envisaged that those would be the immortal numbers inscribed on his intercounty epitaph.

But to condense Setanta’s legacy down to such simple statistics would be as much a disservice to him as it would be to the game itself. Hurling has never been a game of numbers, but rather a game of moments to be cherished, a game of memories to be treasured.

And for one glorious summer, Setanta gifted us with enough of those to last us another twenty years.