And so ends the strangest of years. 2020 will live on in infamy for the rest of our lives. So much has happened in the last 12 months, and yet, at times it felt as though nothing was happening at all.

Our annual look back on our articles on Balls.ie reveals a year filled with frustration, anger, and disappointment, but also one full of joy and inspiration.

Over the course of the week, we are sharing some of our favourite pieces from the maddest of years to relive some of what you may have forgotten or missed in 2020.

You can read more of our favourite pieces here.

---------

In the blink of an eye, you can go from the best to the basement. Success is often fleeting, and scaling the mountain takes longer than cascading down it. 2019 was a remarkable year for Irish sport in every sense of the word: the collapse of the Irish rugby team a flagrant focal point.

In the space of a year, they went from world beaters to no-hopers. There were post-mortems and investigations aplenty in the aftermath of the World Cup. The IRFU even surveyed players and conducted a post-tournament review which they revealed - partially - in a media briefing.

Yet this is a far from rare phenomenon in Irish sport. Throughout recent history, there have been several stark drop-offs across numerous sports for countless reasons; stemming from tactical, structural and psychological failings.

It is hard for teams to avoid the pitfalls that prompt a dramatic decline because no one can agree on what it is they did precisely wrong. While revisiting these bleak spells can seem futile it is important, both in terms of what went wrong and how to avoid it.

Here are some of the great declines in Irish sport and what we can learn from them.

**********

Kerry

Charlie Nelligan remembers looking two of his former team-mates in the eye when he met them at a funeral on the Saturday before the 1991 Munster semi-final against Cork. The Kerry goalkeeper had soldered with Denis 'Ogie' Moran and Eoin 'Bomber' Liston for over ten years. He knew the county footballers recent decline hurt them as much as it did him.

"Will ye do it tomorrow?" they asked, concern evident. Losing to their near rivals was never an option. Least of all when they were coming to Killarney as defending All-Ireland champions.

"I would never be one to say we will go out and win. Never in my born days would I say something like that. I just was not one for bullish predictions," Nelligan recalls now. "But I said to Ogie, 'we will beat those boys tomorrow'."

The Kingdom endured a rare dry spell post-1986. They would not make another All-Ireland final until 1997. In 1987, '88 and '89, they were knocked out by Cork.

"We’d a lot of players hitting the 31, 32 mark. I suppose the legs were not there. Most of them were there since 1975. That is a long time. Bodies were tired.

"Myself included. We were probably weary. You had guys that were there for the last ten, fifteen years."

There was recognition that a new cycle was required but it was easier said than done. Mick O'Dwyer dropped Páidí Ó Sé for the Munster final in 1988. In an era when there was a much clearer distinction between the starting 15 and everyone else, it would end up being discussed on the Late Late Show.

"It was a massive shock altogether. For Paidi more than anyone else," Nelligan explains.

"But Mick O had his way. He worked on our heads, that was half the battle. Today’s footballers have lads talking to them every day, so many fellas involved in the team. Mick O was our psychologist, trainer, coach, tactician, manager.

I remember he had Paudie O'Mahony breathing down my neck, doing his own training and egging me on, while I was breathing down his. That was his bit of psychology. He tried to build it again."

Combined with the change was the fact that Cork were coming. Nelligan is adamant Kerry's performance did not drop considerably post-86, but they met a reinvigorated foe.

"Stand back and look at it. Cork won the All-Ireland in 1989 and 1990. They won the double. That did not come overnight. They were building for two or three years before that."

In 1989, Mick O'Dwyer stepped away and Mickey Ned O'Sullivan took control. They eventually got the psychological preparation right, but it took an awful shock to get them there.

The 1990 Munter semi-final in Páirc Uí Chaoimh ended in a 15 point hammering. The seven-time All-Ireland winner's agony at that is evident even now.

Going in at half-time in 1990. You could feel the game was over and I remember Billy Morgan standing at the entrance clapping his players. Okay, he was clapping his players but he was looking at us. That really, really hurt. That was never going to happen again. Mickey Ned picked up on that. He had us so up for it in 1991. So focused.

Lookit, I know I had great years. All-Irelands. But that win in 1991 was the happiest day of my life. Beating Cork, All-Ireland champions, in Killarney, by a point!

Harrington

Kerry is not the only team to discover relentless success is near impossible. In 2008, Padraig Harrington was third in the world rankings having won the Open Championship for the second consecutive year and secured the USPGA Championship.

2009 brought mixed fortunes and his first winless year in a decade. By 2010 he had dropped outside the top 20 and missed the cut in three of four Majors. It wasn't so much an immediate drop as it was a steady decline.

His ascent had been astonishing. It was 1995 when he won the Walker Cup and made moves to turn pro. Seven years prior to that he won the Leinster Boys Championship at the Royal Tara Golf Club in Meath. Watching on that day was local youngster Paul Keane.

Keane kept track of Harrington's career since then and in 2012 while working as a sports journalist he wrote a book, 'Inside Padraig Harrington’s Head, Obsessed’.

The biography featured 30 interviews including Paul McGinley, Colin Byrne and former coach Bob Torrance. Harrington broke links with the intense Scotsman in 2011. For fourteen years they worked together, enjoying success and enduring fervency that often caused tension.

Harrington always maintained he could only play "with fear". That is a mentality that stood to him at Royal Birkdale or Oakland Hills in 2008. However, there were times prior to his commonly cited drop-off that it affected him.

On the opening day of the 2003 Irish Open he shot a 69. That was a score that left him with a great shot of winning. So after he finished, Harrington went to the range with Torrance in tow. For four hours, the duo stayed out in the wind and rain. This was a hot-streak, successive splendid swings and the 32-year-old was afraid to walk away. As if he might lose it by going home and resting.

In the end, he finished 76th in that tournament.

One of the reasons cited for Ireland's World Cup failure was sustained anxiety. Being on edge can only serve you for so long. Keane sees something similar in Harrington and his relationship with the veteran coach.

"When you look at the reason they broke up in 2011, Harrington was asked and he said whenever he was on the range he could feels Bob’s stare. Almost judging, nitpicking over him. That was good for him seven, eight years previously, but he felt it was too intense at that stage of his career.

This is something that didn’t go into the book but Torrence was really sad at the end of that lationship. I went over and meet him. He finished with Harrington in July. It was still raw. He chatted away.

The following summer he rang me out of nowhere about the book. But he really just wanted to chat about Harrington. He would have said, and Harrington would have said, it was father and son stuff.

But Harrington was moving closer to biomechanics and scientific feedback. Back and forth to an institute in California. That is all numbers, feedback, data. Not someone there watching you.

"To sustain these things is almost impossible. He delivered for 13 months, won three majors. Jordan Speith was the same. McIlroy, not far off. Tiger is an outlier. The rest do it in short bursts, a moment in time. You just get to that level but find it hard to sustain it."

It only takes a minor change to produce calamitous consequences.

"Look at his putting stats. In 2008, he was tied fifth in the PGA Tour. He was almost maxing it out at that stage. Then if there is a drop-off in any of those areas, particularly putting, the whole thing suffers. It drops off a cliff. The following year, 2009, he was tied 104 in the putting. Same in 2011.

"Golf is tiny, tiny margins. In 2008 he had an average of 1.74 putts. In 2016 he was 1.77. Basically the same, but the difference was tied fifth versus tied 108th. A fraction of one and you drop a hundred places. You can apply that to any area of golf."

Yet Keane is fairly certain Harringon does not regret embracing that intensity in his early career. When he started the book, he approached the golfer's manager to tell him he was working on this project. This was done as a formality more than anything, Keane did not need to be told that Harrington had no interest in participating.

He carried a slight fear that the title might be an issue. After all, who wants to be known as obsessed? But those fears were put to bed a short time after publication.

I got a handwritten letter from him. He said he hadn’t read it but I wonder… He claims himself he hasn't read anything because he once read a headline and it affected him so he swore to never read that stuff again.

He said something along the lines that his people said it is a good book and thanks for your efforts. Hopefully, I will read it when I retire.

As for the criticism that focuses on the swing changes?

"He was constantly changing. In 2007 he was drawing the ball right to left. Then he was fading in Birkdale. He was always changing but inevitably, you don’t get the right tweaks all the time."

Ultimately, you live and die by the sword. It served Harrington well overall and Keane stresses that his overall career should be defined by the stunning highs it hit.

"I will never forget the 2012 US Open at the Olympic Club. He was coming up the 18th and had a shot in. I think if he birdied the hole he had a chance at a play-off. Afterwards, he said he was trying to hole his shot. It was a 9-iron or a wedge from 50 yards.

"He was trying to hole it! A really tricky pin placement, if he just put it within ten foot he had a chance at a putt.

"Yet he was standing in the middle of the fairway trying to hole a shot, million to one! That was his mindset. Go for it. There is always better to strive for but maybe you won’t always get it. I think that gradual decline comes.

"It is only ten years ago he was great. In 30 years time, we will forget that tough period. He will be a guy who won, had his majors, reached his highs and then dropped off. It will look perfectly normal. It was a drop-off but it was a drop-off from such a height. A textbook career arch."

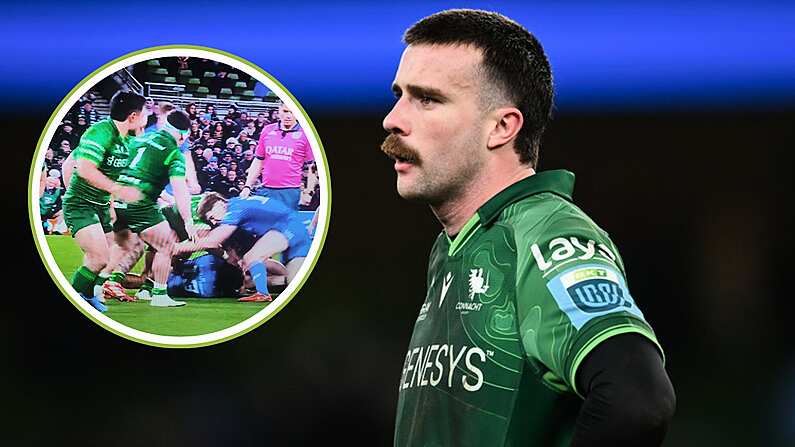

Connacht

A team that enjoyed a similar arch was Connacht. The Westerners shocked European rugby when they won the Pro12 in 2016. That was the result of shrewd recruitment and intelligent coaching under the stewardship of Pat Lam. Backing it up proved a step too far as they fell to an eighth-place finish a year later, closer to the bottom than they were the top.

On the opening day of that season, Connacht lock Andrew Browne caught sight of something in the dressing room that stopped him in his tracks. As he was pulling on his jersey, the gold Pro12 symbol was there starring back on him.

"Jesus, champions. There is an expectation on us now."

The Sportsground was home to its fair share of hardship before then. If anything, it made the achievement all the sweeter.

"I remember saying it when myself and Mul (John Muldoon) finished, we were involved in some terrible years. Like tough times leading up to that. 2010, '11, '12.... We were in the Heineken Cup at the time and that coincided with losing 13 in a row.

"That experience instils a lot in you. Resilience. I think when we did get to the stage where are performing, those difficult times, they did stand to us. You never forget."

But the underdog tag wears off fast and Connacht were thrust into a situation of which they had no prior experience: "Because we had won, we were more public. There were eyeballs on us. So you see all the criticism. Weirdly, old insecurities come back again."

The continuation can only come when a team strikes a fine balance. Too much change and you deviate away from what made you successful in the first place. Too little and you risk stagnation. Browne is reluctant to point to one stand-out reason for their regression, despite the apparent need for a definitive answer.

In reality, it is more complicated than that.

"There were a few different factors. We felt like we had to live up to it, there was a massive amount of pressure then. We had to perform. Subconsciously, that has an effect. I also think there was a bit of complacency from our part.

"You can’t pinpoint one factor, at least not if you want an accurate analysis. There were several things."

Lam's outfit went from under the radar to a sitting target. Tactically, that had a big impact. Browne's team-mate on that successful team, Shane O'Leary, suggests they struggled to adapt in the new season.

"Connacht did not kick the ball often, we were running a lot. Teams worked that out and defended higher. They saw we were trying to get to the edge, so they came up quickly and made us throw harder passes or balls over the top. That is difficult. Teams defended differently to the year before. We just did not execute as well."

Browne is in full agreement.

There was definitely a case that teams figured us out a little bit. We played 2-4-2, which was very successful. Teams figured it and we continued to play it, which I should add was the right thing to do. Why change? It worked. But teams started to figure it out. We had to adjust from the start of the season.

Tactically, they just looked at a lot of video of us. It is surprising they didn’t find it out in the Pro12 year. But then a year later, teams just shot off the line with max pressure. We found it tough to adjust.

O'Leary vividly remembers their first team meeting after the Pro12 success. It was the outset of a new season and Connacht was setting its collective goals for the year.

"The previous year our goal was to get into the Champions Cup. Goals changed as the season moved on, but that was the organisation’s goals. To be in the top competition in Europe," he explains. "We spoke about backing up our trophy the following year. Our standards changed, but you can't overachieve all the time."

This prompts an interesting question. What if a team's success is, in fact, the outlier and the supposed dip is merely regression toward the mean?

Clare

A side who have found themselves at the centre of such a debate is the 2013 All-Ireland hurling champions, Clare.

Davy Fitzgerald's outfit went from lifting the Liam McCarthy in 2013 to not winning a Championship game in 2014. Their starting wing-forward was Colin Ryan.

Triumph to failure. Is it ever as simple as that? Having been put out of Munster by Cork, Clare's 2014 ended at the hands of Wexford after a replay.

"It is nearly an Irish thing, isn’t it? If you don’t win, don’t back it up, it is failure. But, we felt we started 2014 very well. We beat Kilkenny in the Park for the first time in I don’t know how long. We were gunning for that.

"People forget Podge got sent off in the first Wexford game. A rule that very few got pulled for, interfering with the helmet. We should have beaten them. We were down to 13 men for parts of the replay! We still had a chance of winning it.

"When I look back on the season, did we try too hard? Did we over complicate our game slightly more in 2014? Did we try and be too smart with it?

"I think you do become a bit obsessive about trying to be better. Trying to do different puck outs and going away from what you were good at. Trying to keep one step ahead.

"Wexford came to Cusack Park looking to take down the All-Ireland champions. You felt it. We were a marked card."

2013 was fueled by a monstrous work rate and physicality that few could handle. For Clare, that fire ultimately blazed too bright. Speculation abounded over burn-out. The wheel began to turn and in the following years, plaudits became unpleasantries.

Davy (Fitzgerald) got the brunt for an awful lot of it. People sometimes forget that. It is easy to make a manager a villain. It became a witchhunt on Davy really.

Obviously, it took its course. There needed to be a fresh voice after the length of time but it wasn’t solely Davy’s fault.

The players were spared no bullets either. This is nothing new, certainly not for Ryan. A self-confessed avid consumer of coverage in his youth, he learned to take it for what it was, in good times and in bad.

"I was in my mid-20s and there since 2007. I had seen probably the hard times and since how fickle Clare supporters were. How the hardship was never very far away.

"To be honest, I enjoyed 2013 in a different way. The younger lads, Colm Galvin and Tony Kelly, they were always lauded by the Clare public. They came from successful minor and U21 teams. That elevates it all.

"The one piece of advice I was always given, Cathal Lynch said to me, 'when you are gone, you are gone. There will always be someone else coming along'.

"That was great advice for me mentally. To say listen, this is short term. A hobby. Work hard but it won’t define you. I got my All-Ireland and it didn't work out in the years after. It is not the be-all and end-all. Life goes on."

**********

In speaking to every participant in this piece, one indisputable factor became clear; success is high-level sport is not simple. It requires a delicate combination of countless different aspects all meticulously calculated to create the perfect concoction.

It is easier and preferable for there to be one clear reason for a decline, but it is not authentic. There is no silver bullet, no one-size-fits-all explanation for the slump.

The monstrous effort required to become a champion is such that sometimes it leads to an unfortunate downturn. In some cases that is a slide yet to be fully arrested. While all would no doubt prefer to avoid that conclusion, there is still solace in the fact they were once the winner. All bar none are in agreement; the view from the mountaintop is breathtaking, even if it just lasts for a moment.