The significance of the kick-out in Gaelic football has increased ever since Stephen Cluxton came along and reinvented the wheel.

The change has come thanks to a combination of individual skill and directorial compulsion. What was once aimlessly long and vigorously contested became routinely short and unchallenged.

In 2016, the GAA introduced a mark to incentivise long kick-outs. A year later Special Congress went a step further and voted in a rule that every kick-out in Gaelic football must travel a minimum of 13 metres and beyond the 20m line.

At the time there was plenty of focus on how this would impact Dublin. Their delegate Michael Seavers was amongst those to speak out against it. If the rule had been in place for that year's All-Ireland final, 13 of Cluxton's 24 kick-outs would not have been allowed.

Much of this commentary missed the point about their approach. The fact that Cluxton went short so often didn't matter. Neither did his retention rate of 79%. The true value of this team's approach lay in the only number that really matters; the one on the scoreboard. 1-7 of their 1-17 total came on their own kick-out.

Two years ago, former Armagh footballer Aidan O'Rourke conducted a pitch coaching clinic on this aspect of the game. Attendees gathered on the sidelines while he stood on the field with two teams and a goalkeeper. Yet before he got into running lines and communication methods, he made one thing abundantly clear.

The obsession with kick-out retention is nonsensical. The true test is converted scores. You can tap a ball to a corner-back all day, rack up a 90%+ success rate and watch helplessly as your player gets turned over time and again. Nothing should be analysed as binary, the overall picture is imperative.

That session came to mind when watching Cavan overcome Donegal last Sunday week. Mickey Graham's side only won 13 kick-outs, Donegal won a monstrous 28. Yet the Breffni county scored 1-3 from their own restart. Donegal could not match that and mustered 0-4.

Tyrone goalkeeper Niall Morgan is at the forefront of this evolution. For him, the retention stat is only insightful when used in context.

"As goalkeepers, we do sometimes judge our performance off how many kick-outs we retain. The percentage is important to me for my own individual performance. But overall and for the team, it is all about what we do with them," he tells Balls.ie.

I have played games where I had 100% but it is because the other team sat back at their own 45 and gave me a short one all day.

On days like that, I would go off the pitch hugely frustrated. I haven’t even had a real kick-out to hit because they have just gifted every one short, then made it hard for us to do anything with it.

On the other days, we could go out and the team pushes up with a high press. Then you get a couple over the top of a high press and get a couple of key scores of it. That is the job well done.

"It entirely depends on what the other team are doing. If they are pressed up, then I’d be interested in my individual performance and how many I retain. But if they give you the kick-out, you can’t judge my performance at all based on a kick-out rate."

Last Sunday week in the Athletic Grounds, Cavan goalkeeper Raymond Galligan went long with the majority of his kick-outs with varying degrees of success. However, every time it paid off it ensured a superb chance for a score.

Early in the first half, Galligan takes his time over the kick-out. He scans, starts to run up, stops, scans again and finally goes long. He is unfazed by the constant cries of 'how long?' from the sideline.

The ball finds Thomas Galligan (red). He has a mismatch against Brendan McCole and catches the ball cleanly.

Note the Donegal defence retreating (yellow). The long ball ensures they cannot get back in time. They are now scrambling.

Galligan elects not to take a mark and instead immediately delivers long to his two-man inside forward line. Martin Reilly (red) has plenty of space to break into as the Donegal defence has not yet flooded back.

Reilly passes to James Smith who is racing towards goal.

Smith stops and handpasses back to Oisin Kiernan. The half-forward kicks a well-worked score.

The Galligan duo drive on to face a different animal next time out. Dublin are the monster that looms large over all analysis because they are the standard-bearers.

"Dublin have it down to a fine art," says Morgan.

"Whenever Cluxton started this whole retaining ball from kick-outs instead of lumping it out, the wing half-backs would move from their position and he just dropped it into that pocket. That brought in the zonal press. Now against the zonal press, they overload sides and take the gaps. It is constant movement."

Pressing takes a delicate combination of timing and discipline. After a set-piece is an ideal time to organise a press, but it can be dismantled if just one player decides to track a runner instead of occupying the space.

"I always say to my boys, when there is a zonal press try to engage the zone. Run towards a fella and make him man mark you. If he doesn’t you are free in a gap. If he follows you, you’ve made loads of space.

"The key to Dublin is beyond Cluxton now. It is the movement of their players. I think Stephen would say this himself. They are relentless. They all move."

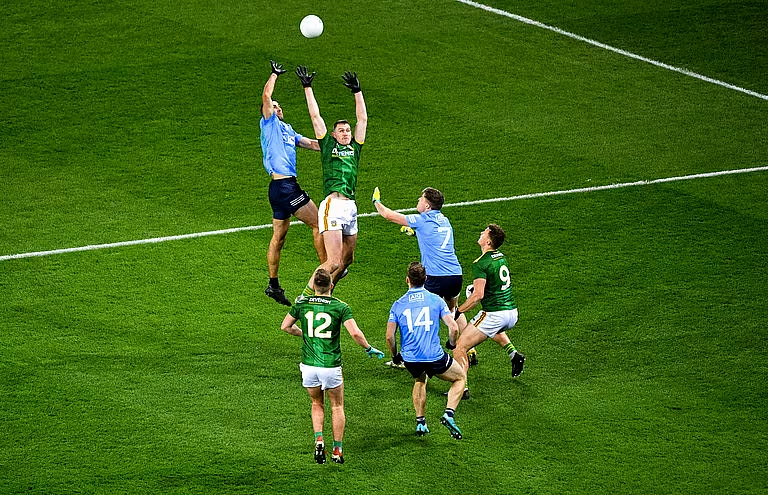

Dessie Farrell's outfit illustrated this perfectly last Saturday week against Meath. They scored 3-1 from 12 kick-outs.

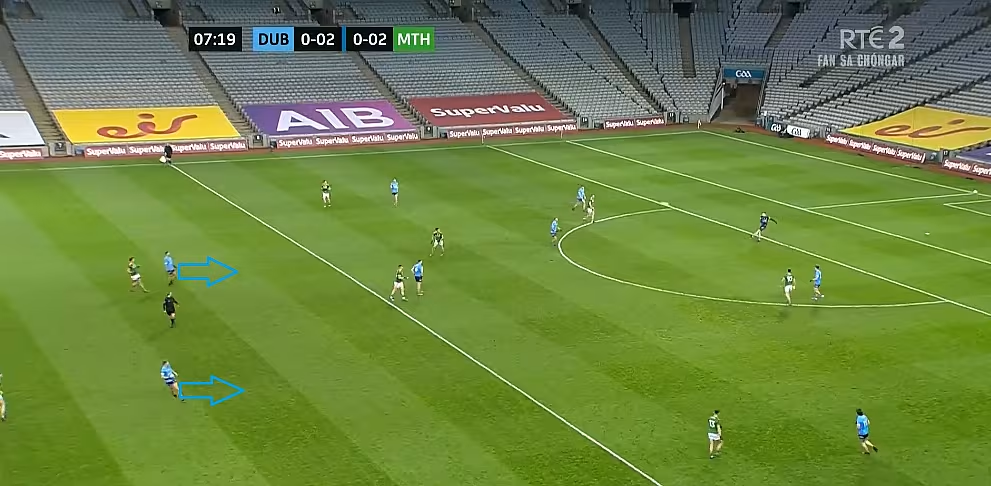

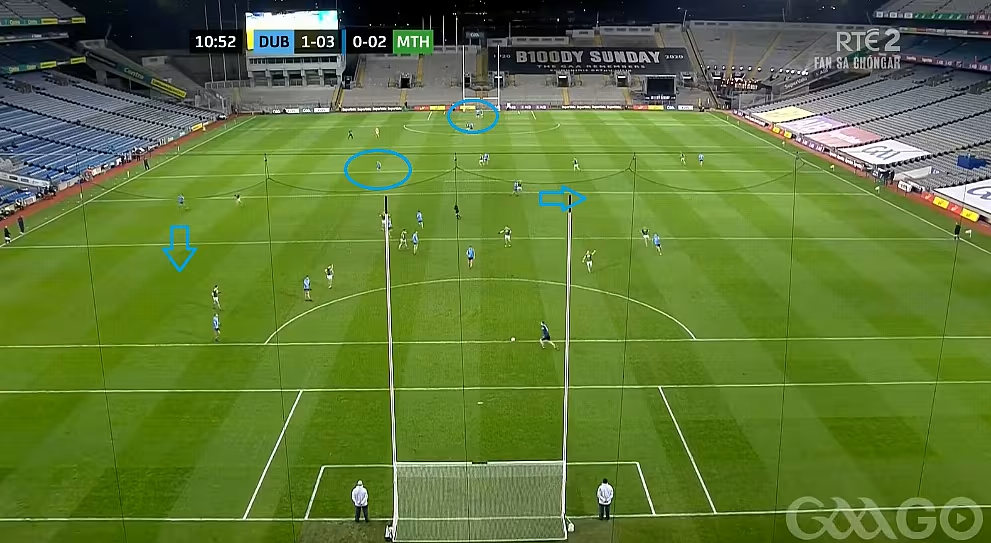

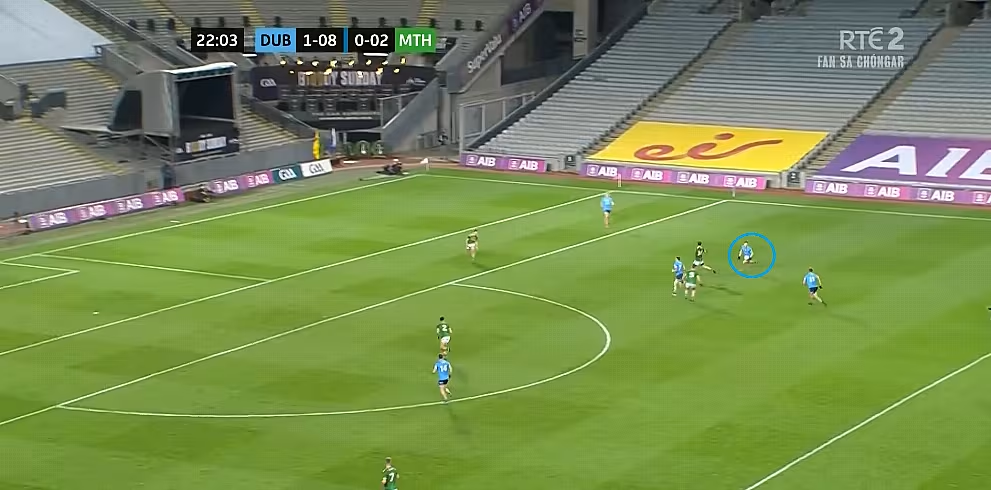

Early in the game, Cluxton goes long with his kick-out. Sean Bugler and James McCarthy both make a sacrificial run to free space in the middle third. Both players are tracked.

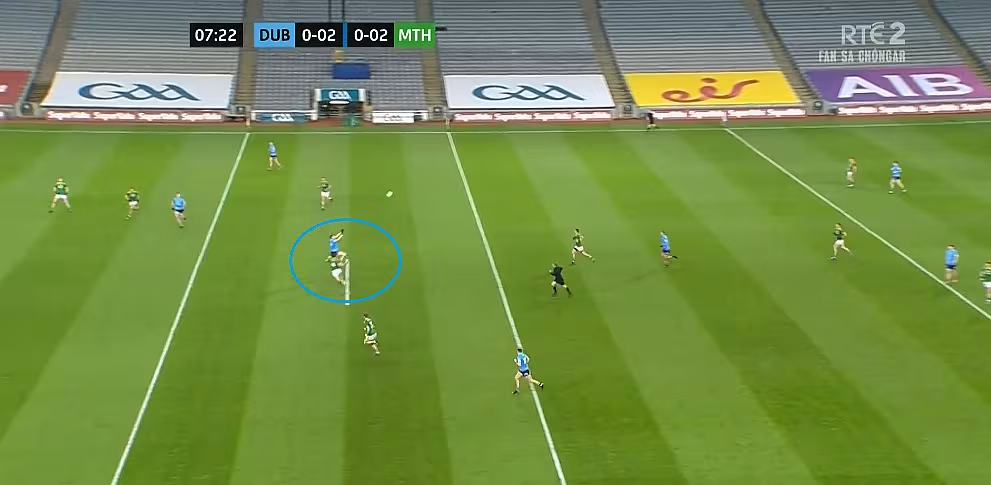

Cluxton can kick long to Con O'Callaghan, one of the best fielders in the country. He is free in a one-v-one scenario in the middle of the pitch. An ideal matchup for the defending champions.

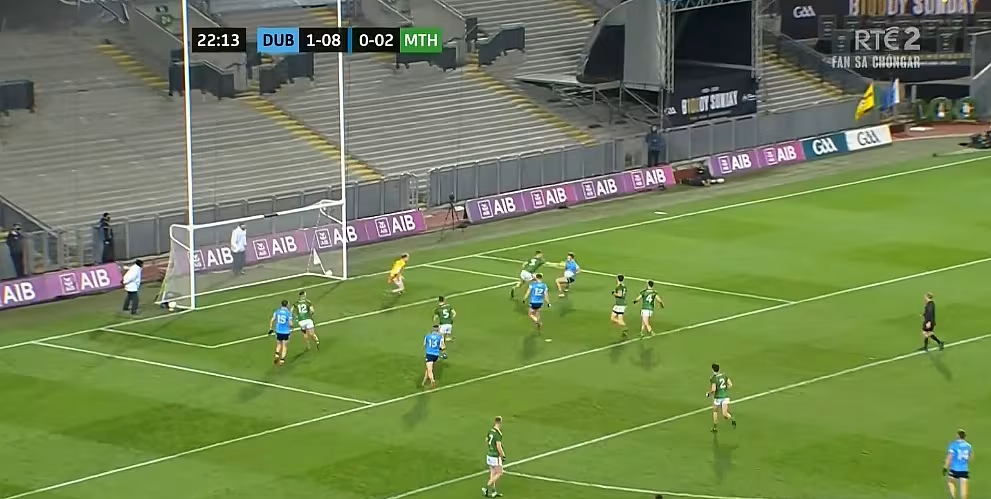

Like Galligan in the earlier example, O'Callaghan plays on instead of taking the mark. After securing possession, the key to working a score is pace. Dublin break forward and every Meath marker finds themselves scrambling back on the wrong side.

It finishes in a Dean Rock goal.

Dean Rock gets an early GOAL for @DubGAAOfficial pic.twitter.com/z9xWeYtQCd

— The GAA (@officialgaa) November 21, 2020

This is the conundrum Cavan will face in the All-Ireland semi-final on Saturday.

"What do you do?" asks Morgan. "Do you give them the ball and know they will be patient enough to work a score or do you press high and allow them that out ball over the top?

"When you go to play Dublin, it is the most taxing week on the brain you will ever have."

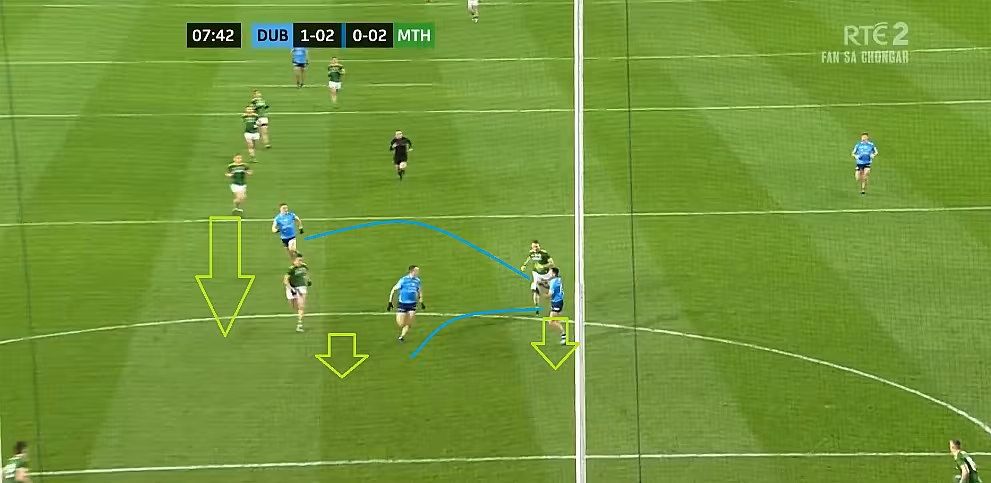

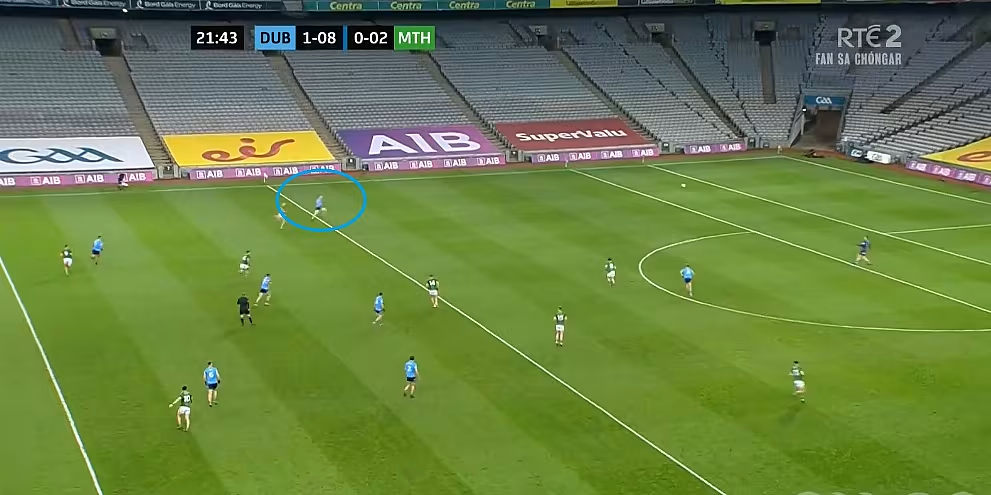

From their next kick-out, Dublin go long to O'Callaghan again. Notice their perfect attacking shape. Two players stay up the field as an outlet. The players near O'Callaghan move away to create space.

Their second goal was a perfect example of the threat from a short option.

Midway through the first half, Meath remained committed to the press. Dublin respond with ten players within their half.

Brian Fenton comes short inside his 45 near the sideline. Meath still have their press on. If they force a turnover, they will have an excellent scoring opportunity. On the other hand, with so many men committed forward, just one Dublin player breaking the line would be a dangerous prospect.

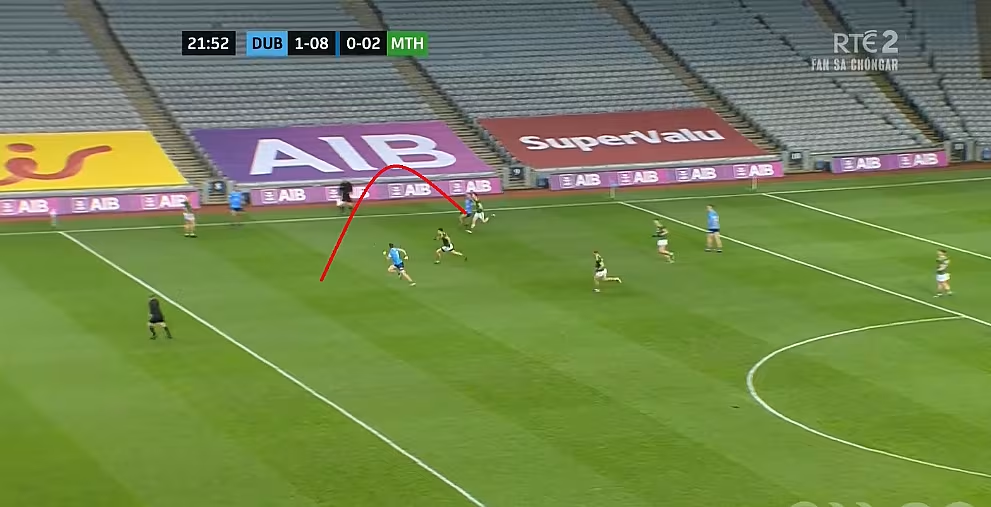

Fenton plays to Johnny Cooper who passes forward to Robbie McDaid. He now has open space to attack. The break is on.

McDaid works down the wing. John Small is totally unmarked in the middle third. This spells trouble.

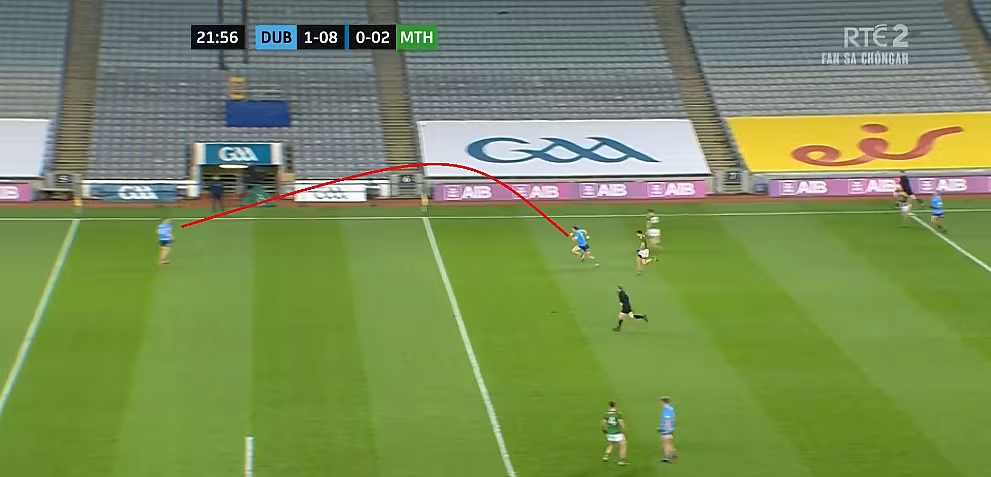

Dublin drive down the wing. Remarkably, when they get deep into the attacking 45 every Meath defender is facing their own goal. This is not good for the Royals.

Less than 10 seconds later, it finishes in a Sean Bugler goal.

For Morgan, it is the movement pre-kickout that is key. While the blame is often placed at the goalkeeper's door when it misfires, the reality is more complicated than that.

"You can only hit what is in front of you. If teams are standing still, the goalkeeper is an easy target to blame. They are great at video work, you see it on RTÉ or Sky all the time, where they stop the play just as the keeper has his head down to kick the ball. Suddenly, they can pick out two or three men who are free. 'Why didn't he kick it there?'

"Sure the other team are running towards where they know the ball is going at that stage. They can see the body shape of the keeper. His leg could be loaded up to go long or whatever.

"I found that with video work. Even with Tyrone, I got blamed the odd time for not going short. You are saying to yourself, at the end of the day, I have started my run up there and I have my leg pulled back and your pausing it now and asking why 'I didn’t go short?'

"I mean we have actually worked on some of that. Changing body shape at the last minute and things but it is a big risk. There is a risk with your connection as well. Sometimes it pays off, sometimes it doesn’t."

On both sides of the ball, the kick-out is now a high-stakes game. Dublin remain the shark at the table.