In the end of season chill of the Cork GAA season, 51-year-old Billy O’Connell did not have time to warm up. Grabbing the first jersey he could find and wearing a pair of wet pants and waterproof boots, the thirty years-retired goalkeeper darted onto the pitch. Once acting as the medic for both teams, Billy was now tasked with saving the Seandún Junior B League semifinal for St. Finbarrs, at the expense of southside rivals Douglas. With the sides level, Billy raced into full forward, where he quickly found himself marked by his 18-year-old daughter’s boyfriend.

If anything sums up junior B my 52 year old dad came on today and marked my 19 year old sister’s boyfriend.

— Dylan O'Connell (@JudgeDyl) October 13, 2019

Following the game was a scene of laughs as the Barrs won 0-13 to 1-9. Starting as a joke between family, a tweet quickly went viral, with over five thousand people retweeting the incident and a further eight thousand people liking it after just twenty four hours. It is a story which captured the heartwarming sense of community which makes the GAA so loved.

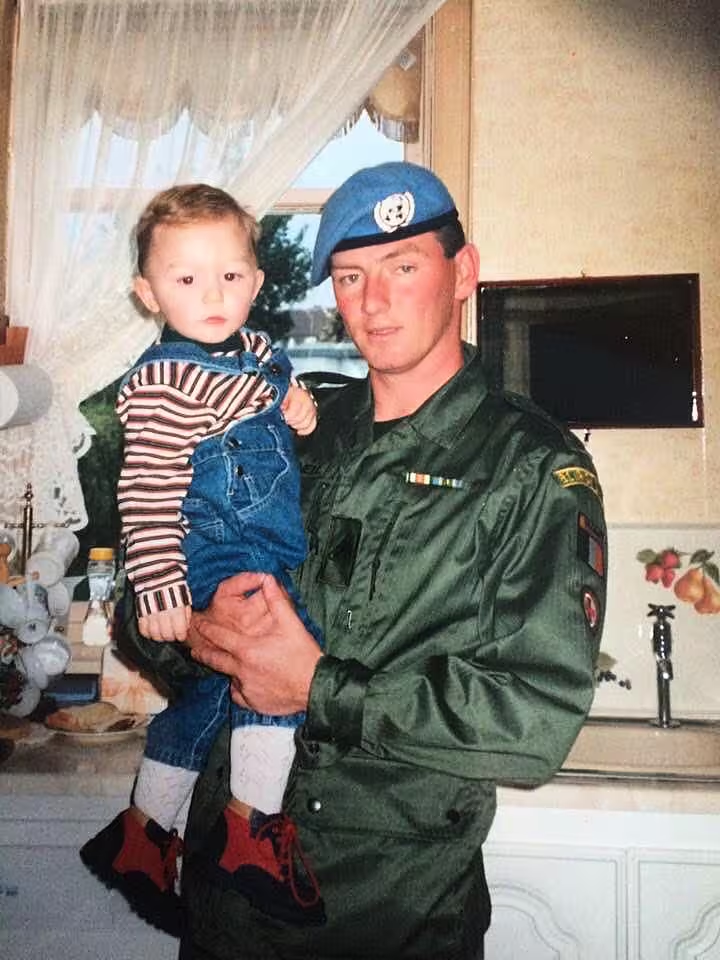

To Billy, this newfound fame marked something different, as five years ago none of this was possible. When most would be looking forward to middle age, Billy’s life was thrust into uncertainty after he was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder at 47. This condition brought about through mental trauma from his experiences overseas with the Irish Defence Forces saw Billy’s mental walls crumble as suffered two mental breakdowns and a suicide attempt.

“When my head was bad I felt I had nowhere to go” Billy admitted, “It brought me to a very dark place. I was afraid to go to bed at night because of nightmares. I was afraid to ask for help because I was ashamed.”

Through this period, sport emerged as the focal point to keep Billy grounded and help him fight through this place of mental fragility,

“My family have been a great support, but sport has been huge in the recovery process. It gave me the opportunity to get off the chair and to go to meet someone. Covering matches as a medic gave me an outlet. It allowed me to mix with people, have a laugh and challenge myself. I am on a very long road, but I have been very lucky to have the support around me that I have.”

Through the GAA, the healing process has truly began. In this, Billy has encountered a number of clubs and colours, in a journey bringing him from the muck of junior football to the fields of Croke Park where he aided in Mayfield GAA’s 2017 All Ireland Junior Football Final success. Two people in particular that he has met from the GAA has been former Antrim hurler Ainle O’ Cairealláin and Irish Wheelchair rugby player Alan Dineen of ACLAÍ in Cork.

Together the pair are the foundation of a community-based gym, acting with a number of GAA clubs, charities and youth groups in the city. Here Billy was been given a place to truly find himself in his healing process,

“When I met Alan Dineen and the staff at ACLAÍ it was not just about fitness on the outside but also fitness on the inside. It is a community gym and that focuses on the physical and mental wellbeing of people and has opened my mind to new ways of thinking and looking at life. I found this place through the GAA and now I volunteer my time inside there by doing massages for charity. I am on my third project for them, now fundraising for the Irish Wheelchair Rugby Team. One of the coaches there is a member of the team and I want to give something back”

In truth, Billy is just one of the thousands in Ireland who will face mental illness in their lifetime. This is a situation which has transcended time and place, dating back as far as 1900 when 0.5% of the whole population were in asylums. Today, through a more detailed understanding of mental illness, Ireland has been shown as having one of the highest rates of mental illness in Europe. Only last year it was reported that 18.5% of the Irish population have been recorded as having at least one mental health disorder with one in four people reported as suffering from mental illness at some point in their life.

A number of studies have looked to examine these numbers for possible causation. One analysis, dating back to the 19th century, has looked at mental health and suicide as a byproduct of the collapse of community through the growth of loneliness and isolation in society. In this gap, a hole has been created for people to feel a sense of belonging. While there can never be a comprehensive understanding, something here sparks when compared to the experiences of Billy.

Through the game, the people and the quest for silverware, the very nature of the club exists beyond the weekly training sessions. It transforms into the lynchpin for community and people, allowing for that break from the pressures of modern life by allowing people to freely mix and build links. The feelings of loneliness and isolation can be confronted in the changing room and clubhouse. A reason is provided to get up and go, and to have people know that someone is looking for you, even when the feeling of nothing is overwhelming.

It could have been a Sunday in Cork, or any ground across the country. The same sense of community remains. Through the fields of the west and the traffic of the cities, the club remains central in the building of community and place. It may be only a temporary fix midweek, but in the face of such issues, it is something.

Dylan O'Connell is the son of Billy O'Connell.