In the last few days, we have launched the website Liatróidí.ie - the Irish language companion to Balls.ie. In conjunction with that launch, we're working with Diarmuid Lyng on a new content series called Plé - it features conversations with well-known people in Irish sport like Paul Rouse and Easkey Britton, in Irish and English, on a wide range of topics.

At the heart of those conversations is the Irish language, the journeys we take to and from it, and how it enriches the lived existence of this island we share.

In this essay, Diarmuid discusses his own relationship with the Irish language, and how the fire of the language was lit in him.

***

A lecturer teaching Módhanna Múinte na Gaeilge took me aside in the hall at Froebel College fadó, fadó, when I was training to be a teacher, and told me straight out that if I didn’t improve my Irish I would fail the course. And it’s hard for a fella to fail in teacher training college.

It’s obligatory to do a tréimhse in one of the Gaelteachts around the country as a teacher and he suggested that the upcoming Easter course was the ideal opportunity.

I had just made the Wexford panel and drinking was out. So myself and three other trailblazers decided we would have a go at speaking Irish with a modicum of sincerity. Three days in and I had a dream as Gaeilge.

The following morning, the strangest thing happened.

Up to that point every Irish class in college brought me to cold sweats before, during and after. And now it was gone. The tension. The fear. The hole in my chest. Gone. The módh chionniollach was still a mystery to me. But it didn’t seem to matter because somehow, a channel opened up where I could craft sentences with the words I had picked up from primary and secondary school.

‘Craft’ is indolent, but comparative to the day before I felt like a poet wandering in to the mainland from the Blasket Islands.

Now, I have to leave that exactly there, because if I was to continue now down the track of how rich my life has become because of that one shift, Liathróidí.ie would never be launched in time.

I feel so certain about the possibility of the language that I have built a business up around the very idea that I experienced. Three days. Being as bang average as I was, I’m convinced that there are hundreds of thousands of people around the country sitting on this untapped well of native understanding and experience.

The first thing I’m generally asked by someone lamenting their relationship with the Irish language is ‘where do I start, and what do I do to recover it’. The answer has changed over the years and will continue to do so, but lately I try to relieve them of the weight of the entire tradition by inviting them to go after only a small part of the language and become a custodian of that.

It’s an idea I stole from Manchán Magan’s project, Gaeilge Tamagatchi, I think. Going in to the live shows Manchán would hand words out to the crowd in the hope that they would become protectors of just that word.

I build on that idea further by inviting them to apply Irish to the area of their lives they are most fulfilled, what they love doing the most, and explore the words, the shows, the writing, on that subject. We speak that language fluently so it opens up the possibility for an increased resonance with the Irish lexicon of their interest.

The idea was cemented by my experiences working on live hurling games for Nemeton and TG4 Sport. Báite san eangach, buried in the net, happens in our minds, Brian Tyres merely decorates the moment.

Balls’ readers speak the language of sport fluently. They know the emotions, the complexities of the relationships, the skills involved and what it all means on the greater stage of life. This represents a great possibility to re-engage with Irish.

In teeing up these upcoming interviews, there was a common expression of uncertainty amongst interviewees in relation to their standard. None are native speakers, not be design, but each are proficient. And still, even in proficiency we are uncertain. It may be a long road ahead.

The interviews are bilingual, and will continue to be, as will the writing, though I have stuck with English for this one to lay out a plan. More importantly than setting out a plan is to extend an invite. An invite to re-engage.

Historian, author and GAA man Paul Rouse is up first. There’s no shortage of talking points from the conversation, but what stuck out most to me was the story of Michael Cusack, a man that spent much of his life promoting the game of cricket in Ireland. He envisioned a team in every parish in the country with regular games between them.

Until he read the story of Cúchulainn in a small pocketbook. One would say in Irish; ‘tháinig rud éigin aniar aduaidh air’. Within a few years he had played a significant part in the establishment of the GAA. That’s a hell of an impact.

Time moves on and these stories fade into insignificance in the face of modern phenomena, but something of the pocket-book endures. There is still the opportunity to orient ourselves homewards, not in service of neo-nationalism, rather to mine the practical wisdom of the place in order to share it with each other and with the international community as a reflection of our collective psyche and spirit.

The understanding is growing that our native language has a part to play in that shift.

As an example, in reference to Cusack’s change of orientation, I wrote; ‘tháinig rud éigin aniar aduaidh air’. Something came over him, or if we were in the folly of direct translation, ‘something came over him from the north-west’.

The directions show up in phrases for many things. ‘Cuireann sé soir mé’, ‘he drives me mad’, or ‘chuir siad siar é’, ‘they put it back’. The directions are fundamental to the language. Even in a room you would ‘go west to open the door’. It was imperative to our forefathers to know what way they were faced at all times. Like Cusask, their orientation carried significance.

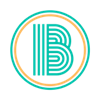

So we orientate towards the carriers of the language, sportspeople we admire for their kinesthetic capabilities, the ones who, like me, are not so far ahead on the journey towards the language, making them ideal candidates to chat with.

Bainigí taitneamh as, bainigí triail as, bainigí treoir as.