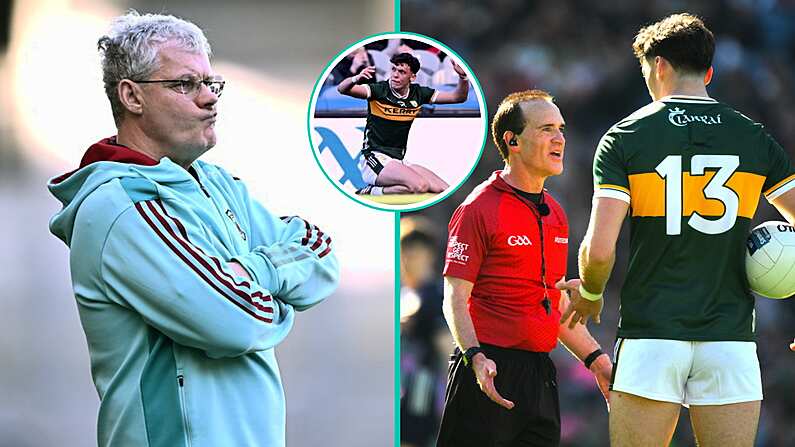

Managers and players often claim they're only looking for one thing. Consistency. That's all they ask for. For the rules to be known clearly by both teams and applied impartially. It's the one thing they want and they're denied it.

Here's Mickey Harte throwing his hands up in the air a few years ago. There isn't a manager and hardly a pundit who doesn't agree with him.

Well, for one thing, absolute consistency, of the sort that inter-county managers demand, is an impossibility. Not every referee will see equivalent incidents the same way. They may miss some incidents altogether. Not every inconsistency arises from a willful misapplication of the rules.

Another thing impeding Gaelic football's striving for 'consistency' is the ancient question of the tackle.

The GAA has been around since 1884 and thus far has yet to adequately 'define the tackle' to the satisfaction of all concerned. After 132 years we might fairly assume that this task is legislatively impossible without altering the character of the game beyond all recognition.

Once one appreciates the vastness of the grey area governing what constitutes a legitimate and an illegitimate tackle, then demanding perfect consistency from referees in their adjudication on the tackle becomes borderline absurd.

When the rules governing the tackle are so blurry and poorly demarcated, then a certain amount of arbitrary decision making is inevitable.

Unlike hurling, Gaelic football lacks within it a coherent and achievable method of dispossession. Hooking a player or flicking a sliotar off a hurl are common staples of hurling. In Gaelic football, dispossessing a player without manhandling or slapping him is more or less impossible. We're open to correction on this, but the only known example of this happening in senior football came when Trevor Giles dispossessed Damian Horisk in the 1994 National League Final. A freak event.

The common way of dispossessing a player now is crowding him until he over-carries.

The combined minds of the Football Review Committee's pored over this question. Their attempt at 'defining the tackle' met with general dissatisfaction among coaches who still, two years on, grumble about the tackle being ill-defined.

The FRC definition said that a player is "allowed to use his body to confront a player" but "deliberate bodily contact" is explicitly forbidden.

This definition asks referees to speculate on whether contact is deliberate or accidental, opening the door to more judgments that managers would no doubt find 'inconsistent'. Cue complaints...

But there is another thing that is monumentally destructive of consistency. The wild popularity of 'common sense'.

While egghead sociologists doubt its very existence, the concept of common sense enjoys a large reputation in both Gaelic football and life in general. It's very difficult to find anyone who has a bad word to say about common sense.

Very often the same pundits and managers who can be heard pleading for consistency one minute will be bemoaning the absence of common sense the next.

What people who demand common sense refereeing are usually asking for is a relaxation of the rules in certain instances.

Tommy Carr was no doubt tipping the hat to the great common sense rulebook in the sky when he lamented the fact that Robbie Kiely was black-carded so early in the game last Sunday. Whether the Kiely call was correct is beside the point. What's at issue here is the nature of Carr's objection to the card.

It was irrelevant whether the foul itself justified a black card or whether the rules demanded a black card. It simply isn't the done thing to send a lad to the line so early. The rules were getting in the way of a good game. It was a classical appeal to the great God of common sense.

Such an approach is ruinous to consistency. How can consistency flourish when common sense keeps butting its oar in, pleading special cases, demanding exceptions, imploring referees not to ruin the game as a spectacle? Common sense is the weed choking the beautiful flower of consistency.

What consistency requires to flourish is a coherent set of rules which can be applied dispassionately. Common sense, for instance, doesn't intrude on the rules of regulations of some other sports. The most spectacularly obtuse example in this regard is golf.

The penalty meted out to Ian Woosnam when his caddy accidentally slipped an extra club into his bag was an affront to common sense. As was the disqualification of Roberto di Vincenzo in the 1969 Masters because his playing partner Tommy Aaron entered in the wrong score in his scorecard on the 17th. Di Vincenzo would have entered an 18-hole playoff the following day but his score was quashed and the green jacket went to Bob Goalby.

The Gaelic football community would regard such rulings as more or less inhumane. The GAA community tends to cleave to the 'spirit of the law' rather than the 'letter of the law' when such dilemmas arise. They may be right on this, or they may be wrong.

But the big virtue of the golfing world's stringency on these matters is that the question of inconsistency never arises.

The next time some yahoo bemoans the absence of common sense in refereeing before minutes later asking where is the consistency in decision-making, just remember that you can have one or the other. You can't have both.