There is a class of sports fan currently at large in pubs across Ireland. A wizened old sage, when he observes a team fall to a defeat he nods his head wearily at all the commonplace explanations for the sad loss that he keeps hearing around about him.

He is unimpressed by your tactical analysis. He sneers at the idea of know-all, chart peddling statisticians throwing their data at him. He is sceptical that even technical ability accounts for the loss. No, no this man delves deeper. He looks into the very psyche of the poor vanquished outfit.

'Bottler' is one of the Irish sports fan most cherished terms of abuse. Rather than merely questioning someone’s technical proficiency, the bread and butter of criticism, it goes further and questions one’s whole character. As opposed to just being a bungler who’s bad at his job, the bottler is a nervy, blithering wreck who’s no kind of man at all.

It does not amount to very forensic criticism. Most of the folk who toss around the term ‘bottler’’ tend to have little technical expertise in the sport on which they are commenting.

The bottler-labellers are not usually drawn from the science and conditioning communities. You won’t find them poring over statistics to back up their assertions. Rather, the bottler-labellers tend to be history-minded people.

When asked to proffer the reasons for their team’s defeat, they will not instance the normal dreary stuff like weaknesses in the full-back line or an off-day in the forwards, but will instead focus on a harrowing defeat in an All-Ireland semi-final in 1944.

For it is in that grainy British Pathe footage with the plummy voiced reporter accompanying that the genesis for so many modern day losses can be found. The deep legacy of ancient failure seeps into a club or a county, defining their vision of themselves as tragic nearly men. You’re kidding yourself if you think otherwise.

Teams who have been training hard and training smart all year are helpless in the face of their historical destiny. Indeed, training and preparation are irrelevant. History is a prison from which they are unable to wake. The past is doomed to repeat itself over and over. The more things change the more things stay the same.

It is difficult to definitively refute the accusation of bottling. This is chiefly because bottling a match can look a lot like losing a match.

The poster boys for bottling big games in an Irish context are of course the Mayo Gaelic football team. At this stage in Mayo’s football history, the sight of them losing a game at all is proof enough for most people that they bottled it.

I was informed recently, for instance, that Castlebar bottled it against St. Vincents when they lost the 2014 All-Ireland club final by seven points. Before that, I had been going around with the thought in my head that they had merely lost the match. But no, no, they bottled it. A much graver offence.

Diarmuid Connolly’s sensational performance, billed by many media organisations as the centrepiece of the game, was simply a by-product of the Mayo outfit’s supposed mental collapse.

In the 2013 All-Ireland final too, the inter-county side bottled it against Dublin when they were defeated by a point.

Once again, the opposition are deemed irrelevant. They are merely extras, bit part players in the production that for some reason RTE persist in showing time and again, that of a Mayo team shitting themselves in an All-Ireland final.

The alternative explanation, put forward by some unimaginative souls, is that Mayo were defeated by a team who are probably slightly better than them, particularly in the forward division.

However, this argument has one big handicap that is impossible to get around. It is no fun.

A plain, colourless line of reasoning which has little time for dwelling upon the impact of priests’ curses, it often struggles to be heard above the joshing about “choking” and “bottling.”

Its much more entertaining to attribute the one-point loss to the Dubs to psychological frailties arising from a sorrowful history of heartbreaking defeats. This allows one to rhapsodise about bubble-permed Anthony Finnerty sending his shot for goal whistling past the post in 1989, John Madden letting Colm Coyle’s hopeful punt hop over the cross-bar in 1996, and Liam McHale trudging disconsolately towards the sideline in the replay. Instead of being a cheerful amble down memory lane, recollection of these incidents takes on the cloak of penetrating analysis. For their effects are still having reverberations today. Fat Larry did not just lose one All-Ireland when he missed that chance.

In the past quarter of a century, Mayo have appeared in seven All-Ireland finals and lost all of them. However, if you examine each final individually, you would find that Mayo were probably underdogs in all of them (with the possible exception of 1997, and even then the consensus was clearly wrong). In 1989, it was Cork who were a bag of nerves, trying to avoid a third successive All-Ireland defeat. This being the era when a Connacht or an Ulster team only appeared in an All-Ireland final when they had the good fortune to meet each other in a semi-final, Mayo were in the final thanks to their win over Tyrone. If anything, Mayo overperformed in the 1989 final.

In 2004 and 2006, Mayo were plainly inferior to the side they came up against. And in 2012, they weren’t quite the machine their opponents were. In 1997, they were marginally adjudged to be the favourites, despite only playing one good game all year (in Tuam). They never showed in the drab final which is now only remembered for Maurice Fitzgerald’s performance. Even, in 1996, Mayo were underdogs in the lead-in to the final. Now, of course, had online betting been a thing back in 1996, Mayo probably would have been short odds to become All-Ireland champions with fifteen minutes remaining. It is certainly plausible that they seized up and changed their approach in sight of the finish line, but matches ebb and flow and they were facing an experienced team legendary for their doggedness.

However, a patient reading of the stats is too much work for the bottle labellers. Their recollection of history tends to be rather more selective. Research is not usually their strong suit. They will not even consult the match programme which is usually heavy on nostalgia. Rather, they place great faith in the power of their own memory and general intuition. Evidence that contradicts their hoary old narrative is forgotten, deliberately or otherwise.

Adrian Logan, the curly haired Ulster based pundit who works for MacLeans bookmakers and used to present that UTV programme that everyone forgets the name of, has said for instance that Mayo “just seem to crumble every time they get to Croke Park.” Logan, speaking before Mayo destroyed reigning All-Ireland champions Donegal in last year’s All-Ireland quarter-final in Croke Park, seemed untroubled by the fact that Mayo had defeated the reigning All-Ireland champions in both 2011 (Cork) and 2012 (Dublin) in Croke Park.

Some teams are more or less immune from the charge of bottling. The Meath Gaelic football team, for example. Even after they surrendered a 10 point lead against Wexford in 2008, the ‘bottling’ insult was not lobbed their way. The bottler labellers have a great deal of respect for Meath. When they won out in that four game saga 1991, they ensured at least a century long immunity from the charge of bottling. Perhaps the only feat that could alter this would be seven straight All-Ireland final defeats. Between 1987 and 1999, Meath were the knowing pantomime villains of Gaelic football. They had the clever resourcefulness and dogged resilience of all the great evil forces, be they Rupert Murdoch or Charlie Haughey. Like Nick Faldo and Steffi Graf, they are one of sports great anti-bottlers, the cold, ruthless figure on the other side of the net when the tragic, all too human, people’s favourite dramatically crumbles before our eyes.

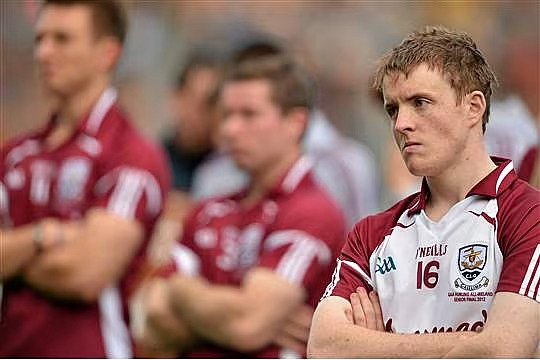

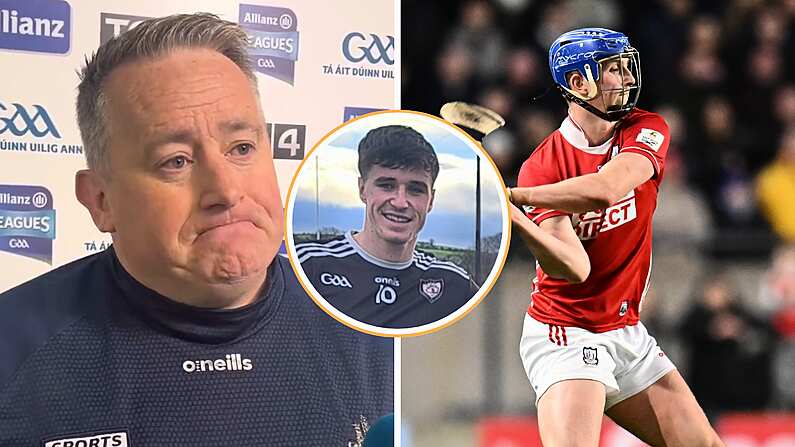

Others teams are frequently tarred and feathered as bottlers; The Galway hurlers, the Limerick hurlers, the Kildare footballers, the Dublin footballers between 1990 and 2010... Most of the time these teams have not been good enough. The Dublin side of the early 90s only made All-Ireland finals because a fair chunk of the late 80s Meath team jacked it in and they were lucky enough to meet Clare (1992) and Leitrim (1994) in All-Ireland semi-finals. And they eventually got the job done in 1995 (and even then they were accused of being bottling that final)

The Galway hurlers lost finals in '93, '01, '05, '12 and '15 in the first and last of those they got considerably closer than most observers reckoned they would beforehand.

While teams and individual sportsmen can sometimes falter through lack of belief, the tendency to ‘choke’ remains an over diagnosed condition in Irish sport. However, the bottler label is likely to remain popular. It belongs more to the realm of slagging than analysis.

Read more: Maurice Fitzgerald Was The Cleanest Man In South Kerry Today Judging By These Photos