On Monday, representatives of the twenty-four senior camogie and ladies football teams gathered to announce that they are playing the rest of the 2023 Championship under protest. 'We as players are not receiving the respect we deserve,' a statement said.

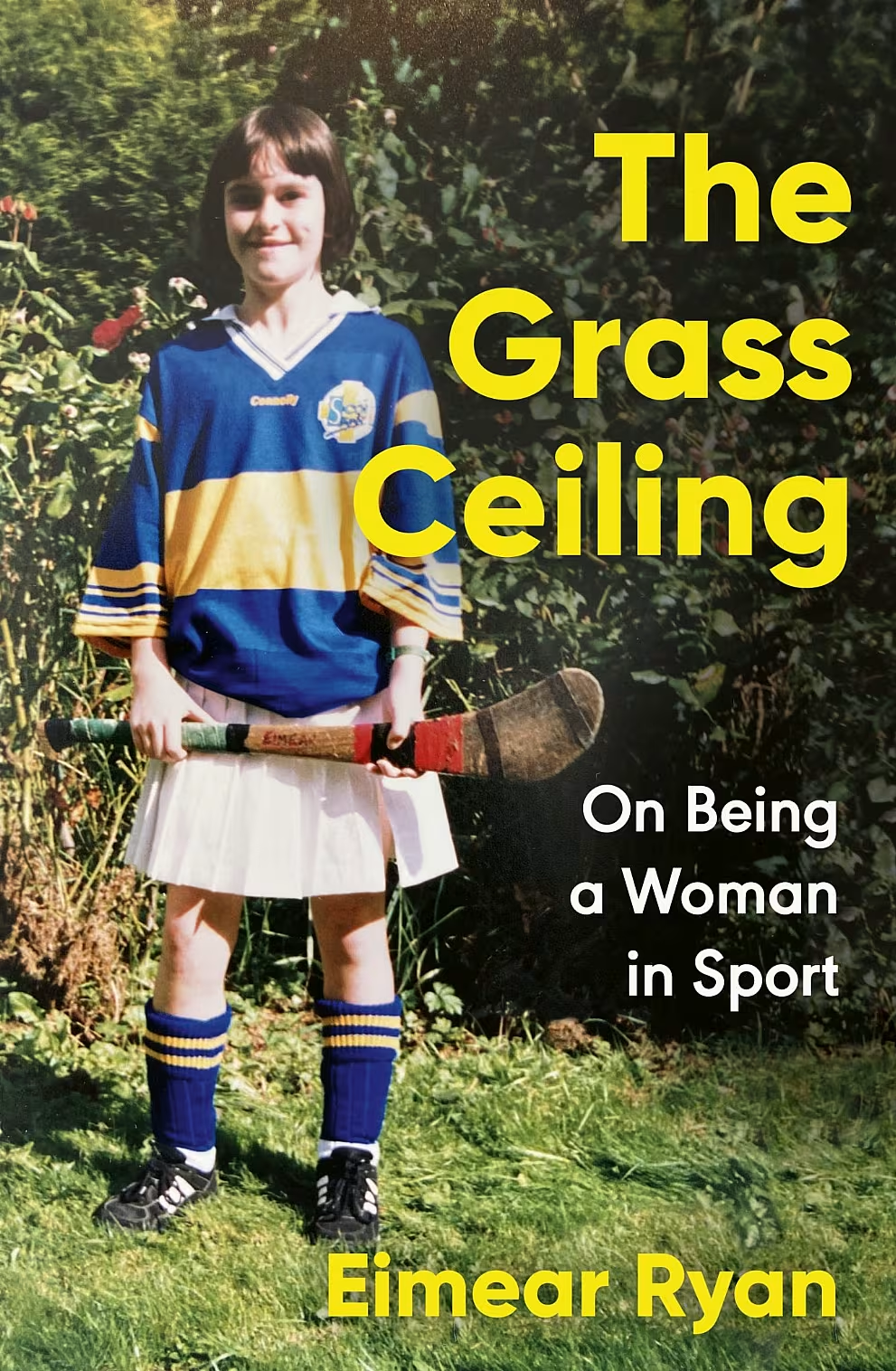

With that mind, we thought it was worth considering an excerpt from Eimear Ryan's outstanding new book The Grass Ceiling. The book tells the story of Ryan's experiences as a hurler. The following passage is about her time as a player in the Tipperary camogie team that won the senior All-Ireland in the Camogie Association's centenary year of 2004. It's a opportunity to consider what's changed - and what hasn't - for women playing gaelic games.

I was called up to the Tipperary senior camogie panel in early 2004 at the same time as my friend and clubmate Julie Kirwan.

Both of us had recently turned seventeen, and had played together on countless teams since we were children: under-12, under-14 and under-16 with the Moneygall hurlers; under-14, minor, junior, intermediate and senior with Moneygall camogie club; schools camogie with Coláiste Phobal Roscrea; and under-14, minor and intermediate with Tipperary. Julie was a tenacious, attacking defender who organized our backline with ease and confidence; I was our freetaker and primary scorer. We were two sides of a coin, and had shared every accolade in our careers. It made sense that we were called up together.

Along with Joanne Nolan of Silvermines, a versatile and stylish player who was drafted in as a sub goalie, we were the youngest members of the panel. I was half in awe of the veterans of the team, who were as close to household names as camogie players got – Ciara Gaynor, Deirdre Hughes, Eimear McDonnell, Therese Brophy, Una O’Dwyer and Jovita Delaney – and of our charismatic manager, former Tipp wing-back Raymie Ryan.

My expectations, as a new member of a successful county panel, were great. Having won their very first All-Ireland in 1999, Tipperary had won four out of the last five. I felt that it would always be this way. More than that, I would be a lynchpin of the next generation of players, a wing-forward on the next All Ireland-winning team, perhaps. None of these things came about. Tipp hasn’t won an All-Ireland in almost two decades, and I never broke into the first fifteen.

19 September 2004; Tipperary captain Joanne Ryan lifts the O'Duffy cup. Foras na Gaeilge Senior Camogie Championship All-Ireland Final, Tipperary v Cork, Croke Park, Dublin. Picture credit; Pat Murphy / SPORTSFILE

It being 2004, the squad was awash with money. People were lining up to sponsor us. About a month after I first started training with them, the entire 2003 panel headed off to the States to celebrate the previous year’s All-Ireland win. Expenses were generous. ‘Do you need a new pair of boots?’ Raymie would ask us. ‘Any physio sessions? A few spare hurleys?’ The sport being, technically, amateur, there was often nowhere for the money to go other than to buy us all a new kit for every championship game. For a time there, I could have outfitted my own seven-a-side team in Tipperary hoodies, socks, skorts – that mystical union of skirt and shorts – and those ubiquitous O’Neill’s navy tracksuit bottoms. Once I stopped training with the Tipp squad, I never wore those tracksuit bottoms again. Even now, whenever I hear the swish of somebody walking past in them, I am transported back to those dressing-rooms, those fields.

2004 was the centenary of the Camogie Association, and rumours swirled that the All-Ireland camogie final would be the curtain-raiser for the hurling final, a slot usually given to the minor hurlers.

This is major, goes the tagline for the All-Ireland minor championships. In its cinematic and beautifully shot TV ad, the heroes are tall and good-looking lads, on their way to being men. The scrawny red-headed kid gets picked last. Girls appear in flashes, slow-dancing with the hero or sitting in rows on the field’s perimeter wall. Watching the lads from the sidelines. The idea of the double-header seemed so obvious and sensible that I wondered why it didn’t happen every year.

Camogie finals pull in a respectable crowd of 15–20,000, but in the vastness of Croke Park, that number can feel sparse. Didn’t the players – and the sport as a whole – deserve the spotlight, the full glare of 80,000 spectators? It bothered me greatly that more prominence was afforded to minor lads than to senior women.

I’m not sure why it didn’t happen, in the end. Some say that it was the decision of the Camogie Association, preferring to have their own day out, too proud to play second fiddle. In any case, it strikes me as a missed opportunity. Women’s sports that are staged alongside their male counterparts – track and field, tennis, swimming – draw comparable levels of interest and attention. When you treat men and women as if they are playing the same sport – which, of course, they are – you get something close to equality of esteem. It helps if, as in the case of the above sports, you have a single governing body looking after both sexes, nationally and internationally.

Gaelic games have not one but three administrative structures: the Gaelic Athletic Association (founded 1884), the Camogie Association (founded 1904) and the Ladies Gaelic Football Association (founded 1974). One might think that there’s potential here for independence and innovation on the part of the Camogie Association and LGFA, but in practice the situation has been disastrous for female players. It’s especially hard on those who play both camogie and ladies’ football: the two women’s organizations seem not to consult one another when making fixture calendars, and dual players frequently find themselves double-booked at both club and county level. In contrast, the GAA – which governs both hurling and men’s Gaelic football – coordinates its fixtures to ensure that there are no clashes between its two major codes, making the life of a dual player workable, if unavoidably challenging.

When the GAA was founded in 1884, it made no provision for female players. The historian Paul Rouse spoke eloquently on the subject for the hurling documentary series The Game. ‘The place of women within hurling’, he said, was ‘absolutely reflective of the place of women in Irish society’. The idea that women might actually play the game ‘doesn’t seem to have dawned on anyone’.

The Grass Ceiling by Eimear Ryan is published by Sandycove and is out now. Information on purchasing the book can be found here.