From the archives: In 2016, Conor Neville delved into how the 90s was an incredible decade for Ulster football.

-------------

Before the 1995 Connacht Football Final between Galway and Mayo in Tuam, one of the on-duty Sunday Sport presenters (forget who it was) recounted a conversation with a Mayo supporter who said he hoped Mayo would lose because he couldn't face the thought of a meeting with whoever happened to be the Ulster champions in the All-Ireland semi-final.

For four straight years at the beginning of the 1990s, Ulster lay spreadeagled on top of the pile, smothering the competition, hogging the Sam Maguire Cup and divvying it up between themselves. Between 1991 and 1994, the Anglo-Celt Cup celebration was merely a taster before the main course in September.

What was so arresting about the period was that it interrupted more than twenty years of Munster-Leinster hegemony and did so seemingly without warning.

The horizons of your average Ulster county were much narrower in the 70s and 80s. Every three years, an Ulster or a Connacht team would pitch up in an All-Ireland final, an invite made possible by the championship layout, which ensured that the two provinces met triennially in the All-Ireland semi-final.

Between 1969 and 1990, the only time either an Ulster or a Connacht champion got the better of one of the other two provincial champions was in 1973, when Galway beat reigning All-Ireland champions Offaly in the semi-final.

Otherwise, their opportunity to play the bridesmaid in September was restricted to those years when they bumped into one another in August. And even in that Division B scrap, Ulster were the poor relation, usually failing to take advantage of their triennial 'golden opportunity'.

Armagh squeezed by Connacht newbies Roscommon in a semi-final in 1977, a year which marked the nadir of the Ulster-Connacht axis. In 1986, Tyrone beat Galway in the semi-final, a win which preceded them blowing an eight-point lead against the oldest team ever to win an All-Ireland a month later.

Troublesome politics can't be ignored. Brian McEniff maintains that Ulster football should have bloomed two decades beforehand. But the eruption of violence in 1969 stamped on any progress.

Going back to the late 60s, in 1968, Down won the senior All-Ireland, Derry won the U21 All-Ireland, Tyrone won the Junior All-Ireland, and Down won the National League, and Ulster won the Railway Cup. So things were on the up. And then the Troubles started in Northern Ireland. Which had a huge effect on Gaelic Games in Northern Ireland.

'EVERYONE SEEMED TO GET THEIR HOUSE IN ORDER'

While the northern revival happened very suddenly at senior level, it was signposted elsewhere. From the mid-1980s, it was clear that it was in the post.

During the fallow years, Ulster counties hardly embarrassed themselves at minor level. Their U18's weren't as cowed as the grown-ups. Derry won All-Irelands in 1983 and 1989, while Down picked one up in 1987. But far more significant and striking was Ulster's sudden dominance in the Sigerson Cup. Ulster colleges had only won three Sigerson's prior to the 1980s, all of them won by Queen's.

While Queen's added another title in the very early 80s, it wasn't until Eamonn Coleman's UUJ team of the mid-80s that Ulster really started rubbing the southern colleges noses in it. Starting in 1986, northern third level teams won six out of the next eight Sigerson titles. Jordanstown claiming three (1986, 87, 91), Queen's picking up two (1990, 93) and St. Mary's in Belfast winning another (1989). All of these teams contained at least one player who won All-Irelands in the 1991-94 bonanza. Ross Carr says Sigerson glory had a major impact on the psyche of Ulster teams.

If you can remember back then, the Sigerson football was being dominated by the Ulster colleges so St. Mary's were going well, Jordanstown had won a couple in the 80s and Queens had won a couple. Those teams were obviously made up of a lot of players from across Ulster. And I think what happened as a result of Down winning, the players from the other counties said "fuck sake, if these guys can go and win an All-Ireland title, surely to God we're good enough. We know what they're like. They're no better than we are."

In Jordanstown, you would have had a lot of the Derry players. Enda Gormley would have been there, Dermot McNicholl would have been there. At St. Mary's, you would have had the Downey's, the McGurk's would have been at Queen's.

From Down's point of view, you have had about seven or eight lads, you would have had DJ Kane, Barry Breen, Gary Mason all at Jordanstown. You would have had Greg Blaney at Queen's with Neil Collins at Queen's. In Tyrone, you would have had the Canavans at St'Mary's, Monroe and a few of the other guys at Jordanstown.

Of the four teams that dominated Ulster at the time, well, taking Donegal out of it, but Down, Derry and Tyrone, those three teams, I would say half of their panels were playing together or against each other Sigerson level.

So, when Down won in '91, you can be quite sure, and it has been stated before, that all of a sudden it was an awakening in the other counties. There was no fear factor of Down, there was no fear factor of the players who played for Down, because they knew them, they played with them, they played against them. And everybody seemed to get their house in order.

Derry great Tony Scullion didn't attend third level. But he saw the increased confidence in Ulster through the Railway Cup. Relative to their stature in the All-Ireland championship, Ulster had always over-performed in the Railway Cup, dominating the competition in the '60s and even into the early '70s. That success dried up slightly through the larger part of the 70s and into the 80s, but even in those years, they snaffled the odd title. By the close of the 80s and into the 90s, they took ownership of the trophy.

It's very hard to put your finger on it. Around that time, the Railway Cup was more important than it is now. My debut for Ulster is in 1987. We won six in a row. 1989 to 1995. There was one year it wasn't played. Winning the Railway Cups in 1989 gave the Ulster players the belief that if we can beat Munster and Leinster and Connacht in Railway Cups, and they're the same players that were playing for the counties, I believe that gave us a great lift at that stage. We would have taken the Railway Cup pretty seriously. Brian McEniff and Art McRory were the management team. I know myself I was very honoured when I pulled on an Ulster jersey.

The sense of provincial unity has always seemed stronger in Ulster - in GAA terms at least - than it is in Munster, where Cork and Kerry never wish each other anything but ill when they reach Croke Park, and Leinster, where anyone-but-Dublin is a fact of life.

We come from our own clubs from our own counties and we have a fierce rivalry up here. But personally, I know myself, I would definitely support the team that would come out of the province, no doubt. I can remember as a young boy, we would be listening to the wireless - there was no television in our house - and the Dublins and the Kerrys were the teams of the 70s and 80s, and God rest my father, he never thought he see the day when Sam Maguire would come to Ulster, never mind Derry, because Dublin and Kerry were so dominant. So, when it comes to the 90s, Down broke the mould and won the Sam Maguire, the rest of the counties were in Ulster were delighted to see Down winning. It gave us the belief.

'MEN FROM DOWN HAD DONE IT BEFORE... IT WAS JUST EXPECTED WE WERE GOING TO DO IT'

Of the Northern teams, Down are by far the most well got among the purists. Their status as the southern artisto's favourite Nordie team was cemented in the early 1990s.

In 1960, they stormed past Kerry to become the first team from Northern Ireland to win the All-Ireland. By 1991, they were still the only one. It was in the '60s that they established their much cherished reputation as Kerry's bogey team. They've won five from five, making them the only team to hold a perfect championship record against Kerry. Considering their current travails, the only way Down are going to maintain the 100% record against Kerry is if they can avoid meeting them in the draw for a few years.

After demolishing Donegal to claim their first Ulster championship in a decade, Down were assigned to meet possibly the least intimidating Kerry team to ever set foot inside Croke Park.

'All's well in the Kingdom again', Jim Carney announced after Kerry held off Limerick in the 1991 Munster Final. The next few years were to prove him emphatically wrong on that score. All was absolutely not well in the Kingdom. The 1991 Munster title win was borne of a Kerry backlash at the Pairc Ui Chaoimh humiliation the previous year, a most un-Kerry like ambush. The ambush isn't a combat tactic usually available to Kerry. It was a very welcome oasis in a very parched landscape but it was not a success made to endure. Indeed, only two players on that Kerry team hung around long enough to win an All-Ireland in 1997, Stephen Stack and Maurice Fitzgerald.

The 1991 semi-final between Down and Kerry was thus a clash between two teams in radically different places. The imposing presence of Pat Spillane and Jack O'Shea on the Kerry team even made it seem like a clash between two different eras.

Once we had beaten Donegal in the Ulster final - and we beat Donegal well in that Ulster final - we got a serious confidence out of that. And within the squad, we started to think, 'there could be something here', without actually going to think about winning an All-Ireland. With all due respect to that Kerry team, you know, Spillane played, Tom Spillane played, Ambrose O'Donovan played, Jacko played. But those guys were in their mid-30s. We felt they were there for the taking.

Down exposed a creaking Kerry team. Peter Whitnell, possibly the least flashy of the Down forwards, blasted home goals either side of half-time. They steamed home by eight points. Pat Spillane, who wore an oppressive looking knee bandage for much of that season, called it quits after that match. Jacko was to follow him out the door the following year.

In the final, they met the most feared team of the era. Meath had already played about a thousand championship games that season, and many of their players were on the road a long time. By rights, Down should have been blue young waifs entering the decider.

The worth of 'tradition' is nowadays dismissed by the more zeitgeist-y pundits. Usually written off as the hoary old fallback of the clueless pundit. The pundit who can't be arsed keeping up to speed with changing trends. But Carr is adamant that the influence and example of the 1960s team had an inspirational effect on the team. They provided the early 90s team with an inner confidence.

We were very lucky that in the lead up to the final, a lot of the boys from the 60s, all of them were still alive and well. They were really good in settling us and preparing us for a game of football. Not that they took over or anything but they were just there for counsel.

People look for comfort and support from a whole lot of different areas. If it works, it's the right thing to do. If it doesn't, people will say, 'what the hell did you do that before?' They gave us a calmness and an assurance. Some people would call it an arrogance. I would just call it a confidence. Because men from Down had done it before. There wasn't a pressure on us to do it. It was just that we expected that we were going to do it. The tradition played a factor. It definitely did for us.

'WE WOULD HAVE BEEN EXPECTING TO WIN IT BEFORE DOWN'

Donegal's victory is distinct from the other Ulster victories in that era in that it didn't have its roots in Sigerson glory. Donegal lads didn't tend to head for the NI universities. What they had won was a couple of All-Ireland U21 titles in the 1980s ('82, '87).

The fabulously democratic Ulster championship in the 1980s reduced them to the occasional, fleeting appearance in Croke Park. In 1983, they were pipped by Galway by a point, falling to a late Val Daly goal. In 1990, they were soundly beaten by Meath.

The county board's bizarre fetish for sacking Brian McEniff every few years at the first sight of trouble hobbled the team's progress. McEniff had five separate spells as Donegal manager across four decades. Amazingly, until Jim McGuinness came along, Donegal never won a provincial title under any other manager.

We would have won an All-Ireland U21 title in 1982 and 1987. And it was an amalgamation of those two teams. Plus we got the likes of Noel Hegarty and Tony Boyle who had come out of minor teams. It was an amalgamation of those two teams that brought the success. It should have come a lot earlier. It might well, in different circumstances, maybe have won in the late 80s.

We would have been expecting to win it before Down. We played Down in the National League and the McKenna Cup and we whipped their ass in both. That was the year (1991) we should have won it.

The All-Ireland champions were taken out of the equation by Derry in Casement Park in the 1992 Ulster semi-final, a day in which Peter Whitnell was sent off and Joe Brolly recalled a Derry player roaring after him, 'that'll be your last big day until the 12th'.

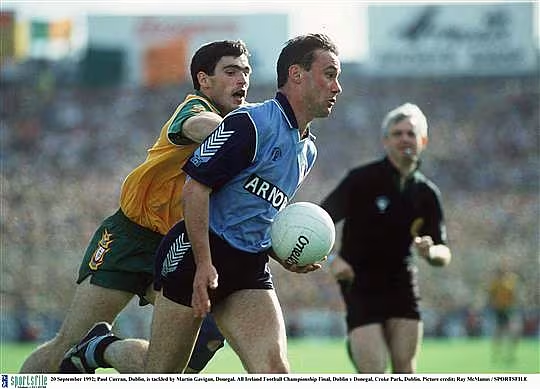

Derry themselves only had one more big day. Donegal won the Ulster final by two points. As Kieran Cunningham has written, '1992 is always put forward as Exhibit A in the impact of hype on Dublin teams'.

The 1992 All-Ireland semi-final between Donegal and Mayo enjoys the reputation of being one of the worst games ever played in Croke Park.

At least one of those Dublin players in attendance that day concurred with that view. In an interview with John Fogarty a few years back, captain Tommy Carr recalled an unnamed Dublin player letting go with a cocky remark as he departed the game early.

I remember sitting behind a group of Dublin footballers and about three of them left with 10 minutes to go and one of them remarked ‘We’d beat the pick of the two of them’.

At that moment I felt that was not a good sentiment to leave Croke Park with. That was the beginning of the end because it is very hard to get rid of that view of the opposition.

Several Dublin players spent the week of the 1992 All-Ireland final doing fashion shoots and radio promotions. Their charismatic but placid manager Paddy Cullen spent some of the lead-in advertising washing machines.

Most damningly of all, an open top bus tour was booked for the city centre for the day after the match. We know what happened in the game. After a gingery start, Donegal came at Dublin remorselessly, passing them to death and winning by four points. It was reported later on that Man of the Match, Matt Gallagher, the All-Ireland winning U21 captain in 1982, didn't kick the ball once in the entire match.

The following day, someone in Dublin City Council went ahead and decreed that the conquerors of Clare in an All-Ireland semi-final should proceed with the open-top bus tour of the city, so the citizens of Dublin could show their appreciation. The citizens of Dublin were uninterested in showing their appreciation.

Paul Curran felt toe-curling embarrassment.

I remember absolutely nobody turning up; we could have been on the 77A to Tallaght. It was surreal to be honest, there wasn't a sinner. I don't know who was involved or who said 'yeah', but it was a crazy decision really... But the reception at the Mansion House was fine; there were the usual die-hard Dublin supporters there to greet us.

Dessie Farrell was similarly mortified.

The whole thing was a disaster. We went down O'Connell Street and, sure, there were people coming back from work and they were looking about as if to say: 'What are these crowd at?'

Tommy Carr wisely refused to attend in protest.

'I NEVER THOUGHT AS A BOY DERRY WOULD BE IN AN ALL-IRELAND FINAL BUT NOW IT SEEMS LIKE THE MOST NATURAL THING IN THE WORLD'

Almost everyone got a go in Croke Park at least once during the 80s. Only Fermanagh, Antrim and Cavan didn't get their hands on the Cup that decade. Tony Scullion won his first Ulster title with Derry in 1987.

Let's be honest. In '87, it was boys against men. We weren't ready for that Meath team. That was a really good Meath team. We were the cubs that day and they were the men. For us to win an Ulster championship was a big thing for Derry that year but we weren't physically ready for that Meath team that year.

Of the three All-Ireland winning teams from Ulster, Derry's success was the most heavily signposted.

They were coming into a rich inheritance from the underage grades. Not only had the bulk of their players starred at Sigerson level, Derry won two All-Irelands in 1983 and 1989. Anthony Tohill was the star graduate of the latter side.

Under the stewardship of Sigerson guru and 1983 All-Ireland minor winning manager, Eamonn Coleman, they rose from Division 3 irrelevance at the end of 1990 to National League champions in 1992.

The Ulster final in 1993 is best remembered for the comical weather. Bouncing the ball was an impossibility. 0-8 to 0-6 was a respectable scoreline in the circumstances. Oddly enough, potted histories tend to give more prominence to the All-Ireland semi-final win over Dublin than to the All-Ireland final win over Cork. In the years 92-95, it was the Dubs v the Nordies game which decided the destination of Sam.

Derry's run to the All-Ireland is heavily documented on youtube, not only in clips of the games, but in interview clips with the players, Joe Brolly being the most prominent.

Their serene confidence shines through. A confidence most untypical of a team going for their first All-Ireland. Scullion says toppling the two succeeding All-Ireland champions left them with little to fear in Croke Park.

We played Down in the first round in Newry and beat them fairly handily and they were the '91 champions. And then we beat Donegal in the Ulster final and they were the champions the previous year. So, that gave us a firm belief going into Croke Park to play Dublin. We respected them but we knew we were as good as them. It was good that we that belief because at half-time in that game, it was 9-4 to Dublin. We really, really knew that when Down and Donegal could do it, why could Derry not do it?

RTE used to set up shop outside Croke Park for the post-match interviews. Joe Brolly, even then a fluid and assured TV performer, conveyed the mood best.

I must say that as a boy I never thought Derry would be in an All-Ireland final but now it seems to be the most natural thing in the world.

'I TICKED A DIFFERENT BOX IN 1994'

Like so many ex-players and ex-managers, Brian McEniff maintains his team should have won more than they did. Unusually, he also feels his provincial rivals sold themselves short. Derry should definitely have added another.

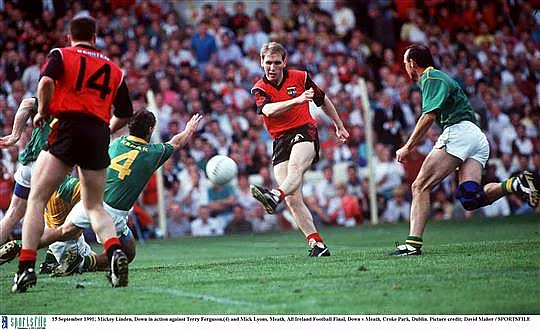

In the end, it was Down who tagged on the second All-Ireland.

They'd been minced by Derry in the 1993 Ulster championship in Newry. The following year, they won a classic in Celtic Park, a game which has been held aloft as the pinnacle of Ulster football in that era and a contender for game of the decade. It was the closest Down came to exiting the championship all year. Had Derry won, they may have completed back-to-back triumphs.

Carr says they were driven by anger at their abject failures in 1992 and 1993.

As a team we were more angry. We were poor champions. We didn't defend our title in the right way in '92. I suppose the strength of character in the team, when every thing is rowing in the right way, that can be a real asset. But it can implode easily if those egos can't be controlled. That's what happened over '92 and '93, we started to implode a little bit.

By '93, the hangover excuse was no longer available. The heavy defeat that was deemed unacceptable. Pete McGrath's scathing comments afterwards prompted a mini-revolt within the squad.

Greg Blaney sensed hostility from the management and walked away. James McCartan joined him in solidarity.

Speaking to us, Carr credits the arrival of Pat O'Hara into the management squad as the key factor in rebuilding morale before the 1994 season. Blaney and McCartan returned in time.

But then someone came into the management team along with Pete in '94 and galvinised the thing again. Pat O'Hara, who was a teacher from Downpatrick, originally from Warrenpoint. In early January, there was a lot of soul-searching. We put in some horrendous sessions. Because the draw meant we were playing the All-Ireland champions in their own home ground. There was no point getting another trimming. Another trimming, we got one at home in '93 against Derry. And then we had to go and play them in '94, away from home this time.

There was more of angry setup in '94. It was a controlled anger that we had to prove... not to prove the doubters wrong but to prove to ourselves that we weren't a one-hit wonder.

I'm not going to say I got more enjoyment in '94 than I got in '91 because you never experience anything like the first one but... I ticked a different box in 1994.

That's the only way I could explain it. It was something that had to be done. And I think a lot of the fellas that played in '91 feel the same way.

In the century before 1991, Ulster counties had mustered eight All-Ireland titles between them. Only two counties had contributed to this haul.

Cavan, whose lofty standing in the roll of honour is entirely due to early 20th century dominance, won five All-Irelands, and Down had won three. In the quarter of a century since, Ulster teams have won nine All-Irelands, more than any other province.

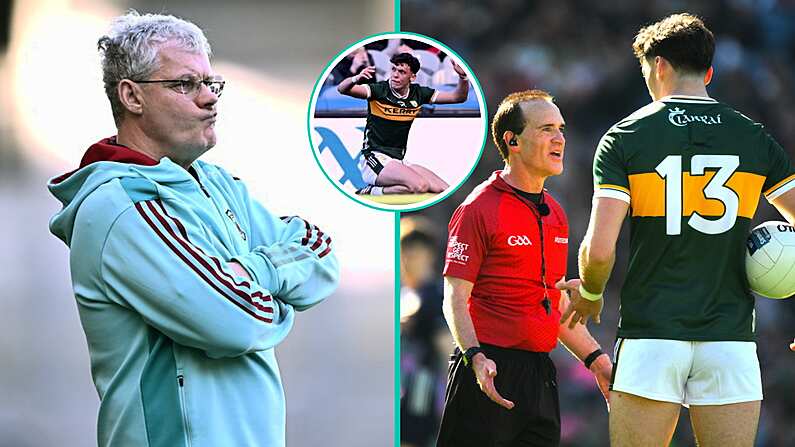

It was Tyrone's turn in 1995. By rights, they should belong in this company. Like the trio of counties that won, they contributed heavily to Ulster's Sigerson Cup boom in the late 80s and early 90s. They also won back-to-back U21 titles in 1991 and 1992.

They had a misfortune to arrive at a moment when Dublin had resolved that they couldn't keep losing finals. After a half decade of cruel losses and crueler penalty misses, the Dubs finally, and mercifully, scaled the summit in 1995. It wasn't the most swaggering of All-Ireland victories and there was a bitter dispute about a ruled out equaliser in the final minute. But they crawled over the line, ending Ulster's reign of dominance.