Roy Keane’s initial exposure to professional football set the template for his footballing philosophy. The young Irishman signed for Nottingham Forrest for £47,000 but his debut, like so many of the notable moments throughout his career, was entirely unexpected.

It was chronicled by Harry Redknapp, in his autobiography, Always Managing.

"One of the best examples of a managerial debut was Roy Keane’s at Nottingham Forest. Brian Clough never worked on team shape. He wanted to keep everyone on their toes, and so it was not unusual for him to even wait until an hour or two before kick-off before revealing the starting XI. Forest were playing Liverpool early in the 1990-91 season and his first-team squad had already travelled up on the Friday before the game.

Roy had played on the Thursday for the reserves and was nursing a bit of a hangover when he was told to call to Cloughie’s house on the Friday night to be taken up to Anfield to help with the kit. Keane rang the bell, Cloughie opened the door and immediately made the youngster drink a pint of milk.

They got to Anfield and, as expected, Roy began helping out with the kit. He was getting boots out and hanging up the shirts. There was 60 minutes before kick-off when Cloughie suddenly told him to try on the number seven shirt. Roy did so, but still had no idea what was going on until Cloughie just turned to him and said ‘Irishman, you look that good you’re playing.' The rest of the team did not even know who he was.

"His advice to Keane was simple. ‘Get the ball, pass to someone else in your team.’ Keane was brilliant that day, even though Forest lost, and he pretty much stuck to Cloughie’s advice for the rest of a wonderful career."

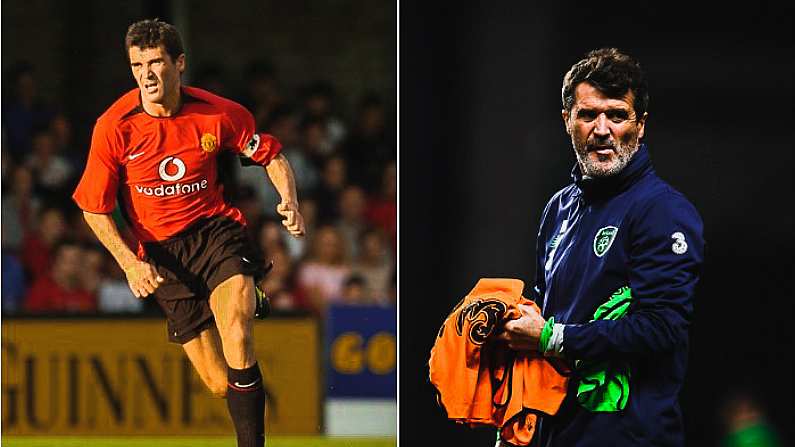

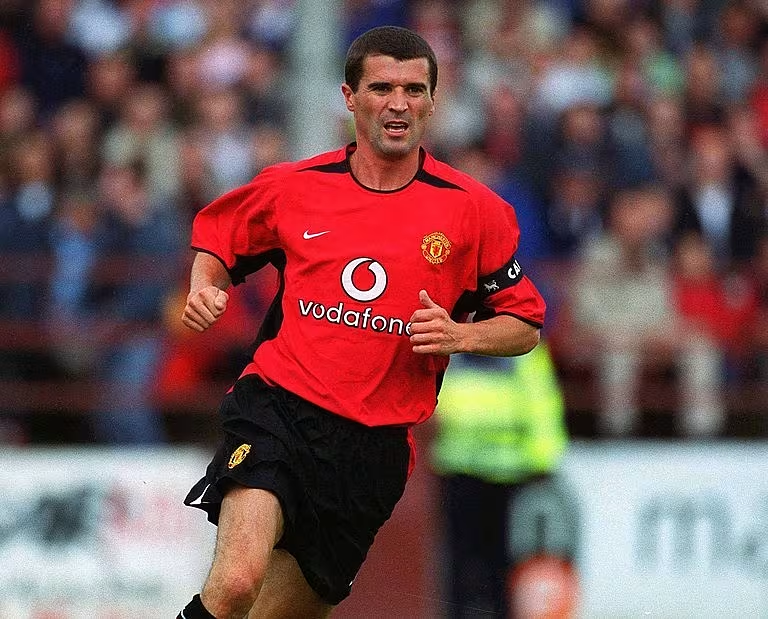

Harry Redknapp was correct. Throughout his greatest days with Ireland and Man United, Keane kept his outlook simple. A mind reader in defence, capable of envisaging an opponent’s plan three moves in advance. An intuitive master of understated passing and a chest-beating commander who lead by example.

His was a game of consistent confrontation. He refused to wilt in the face of adversity. His greatest performances, against Juventus in '99 and the Dutch in '01, were driven by sheer energetic engagement. Bar some notable exceptons, it served him well. Roy Keane would not adapt for anybody.

Yet, his sophistication on the field was never articulated off it. That infamous 2005 MUFC TV rant after defeat against Middlesbrough is a fascinating insight into Keane as a player and his view on where the team was failing.

Where did it all go wrong? “No character.” Why had they conceded a goal? Van Der Sar should just “save that.” John O’Shea? “He’s just strolling around when he should be busting a gut.” Kieran Richardson? “lazy defender.” Alan Smith? “Doesn’t know what he is doing.” On the subsequent fall-out from the interview: “I gathered them all in the dressing room and told them it was all fucking nonsense.”

Bar-stool talk. Outrage normally propagated by outspoken pundits in the name of entertainment. Cliché-driven attacks rather than constructive criticism. No one is left any the wiser on their role in the team, areas they need to improve or the tactical adjustments that are necessary.

In an era where the most successful managers protrude as dedicated sculptors armed with a chisel to craft technically moulded and well-marshalled players, Keane is a demolition man armed with a sledgehammer as he smashes picture frames for the sake of passion.

Studying is not teaching and playing is not coaching. Countless top-level players have failed to make the transition to management because it demands a different skill-set. By no means does his coaching career affect his playing one, that legacy remains assured.

Keane himself opened up on this deficiency in his second book. “It’s almost like having to go back and do your driving test. I can drive, but I’m not sure I can tell you the rules of the road.”

Martin O’Neill made several poor choices during the course of his reign, but one of the worst was to recruit Roy Keane as his assistant manager. The aggression and attention he commanded during his playing career carried over to his coaching. The spark that ignited the fuse on the bomb that was the O’Neill/Harry Arter Whatsapp fiasco and contributed to the management team’s ultimate demise.

Perhaps O’Neill foresaw the relationship as a good cop/bad cop partnership. Yet, the Irish team had a proud history of full commitment despite limited ability. The situation did not need inspiration but organisation.

Roy Keane the pundit will enjoy greater success than Roy Keane the manager. His fierce nature lends itself to that profession, as he demonstrated during the recent World Cup. In many ways, it is a more desirable outcome.

One can only imagine what Keane the pundit would have said about the recent mediocre performances of the Irish team were he not facilitating them.

Sunderland, Ipswich, Ireland and Aston Villa, with every step of Keane's managerial career came conflict with his own players. Continuing to garner experience is a suitable means towards evolution, but right now the same searing traits that made a world class player are forging a substandard coach.