Though the tradition has become more sporadic in recent years, Manchester United have historically boasted a strong Irish contingent in their midst.

The route of this custom can be traced back to Patrick O’Connell, the first Irishman to captain United. He signed for them shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, in May 1914. Dubliner Johnny Carey did a fair bit to cement the custom when he captained United to victory in the 1948 FA Cup, Matt Busby’s first trophy as United manager. From Kevin Moran and Paul McGrath in the eighties to Roy Keane and Denis Irwin in the nineties, United have habitually picked up the best Irish soccer talent.

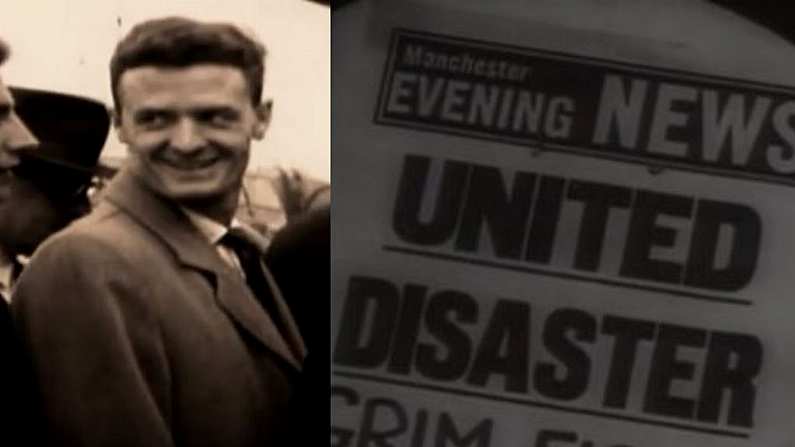

But the Irish conveyor belt has supplied United with few talents as naturally gifted, as Liam ‘Billy’ Whelan.

Born in Cabra in 1935, Whelan played for Home Farm before being spotted by Busby’s renowned Irish scout Billy Behan, joining United at the age of eighteen.

In his excellent biography of Matt Busby, A Strange Kind of Glory, Eamon Dunphy describes what kind of talent Whelan was.

He had the basics and a bit more. He had beautiful control, scored goals and was a tall, strong lad not easily intimidated.

Bobby Charlton held the Irishman’s footballing intelligence in the greatest regard.

Billy had brilliant close control and was a natural goal scorer. His forte was to scheme, to shape possibilities with his skill and excellent vision. He scored so many goals from midfield, he would be a wonder of today’s game.

The Busby Babes

In the 1950s, Matt Busby and his assistant Jimmy Murphy were changing the parameters of football in England - both in the way it was played and approached.

With a strong focus on youth, a novel approach at the time, United won the first of five FA Youth Cups from 1953 to 1957. Liam Whelan was a key figure in the first three, before graduating from the youths to the ‘The Babes,’ in 1955.

The 1956/57 season saw United win the First division championship for the second year in a row. Whelan scored 33 goals in 55 appearances. The Cabra boy was scoring more than a goal every other game, long before it was common practice for strikers. In a total of just 95 appearances for United, he would find the net 52 times.

As January turned into February 1958, Matt Busby’s dazzling young team were tussling with Wolves at the top of the First Division, a keen eye set on a third consecutive championship.

The two teams were due to meet at Old Trafford on February 8th in what was being billed as an early title decider.

Prior to the Wolves game, Busby’s team would travel to Yugoslavia to play Red Star Belgrade in the second leg of the European Cup quarter-final. With United leading 2-1 from the first leg, a 3-3 draw in the away leg saw The Red Devils progress to the semi-finals.

Whelan did not feature that night. But the average age of the Manchester United team to take on Red Star, the last The Busby Babes would play together, was just 23.

The Crash

The aircraft carrying Whelan and his young team mates home from Belgrade was a twin-engine BEA Elizabethan, captained by James Thain, a vastly experienced pilot, formerly of the RAF.

Following a scheduled stop off in Munich to refuel, Captain Thain had to abandon his initial take off attempt as the Elizabethan failed to reach the required 119 knots, the speed at which the aircraft could become airborne.

Thain then taxied back to the beginning of the runway for a second attempt, but this too had to be abandoned when the Elizabethan failed to reach the required speed.

The captain and his co-pilot Kenneth Rayment, decided to return to the terminal to investigate the issue further.

Whelan, a keen card player, had settled in for a game of poker with Northern Irish goalkeeper Harry Gregg and others. The game cut short, the card club disembarked the aircraft along with their team mates and the other passengers, while Thain and Rayment were joined in the cockpit by Station Engineer, William Black.

Black explained to the two pilots that the issue they were having was one commonly experienced by Elizabethans at Munich airport, due to the high altitude.

Black told Thain that to simply increase the engines throttle up to full power more gradually, therefore extending the take-off length, in order to reach the speed required. Problem seemingly solved, the players and other passengers, who were now back in the terminal bar, were recalled to the plane.

The atmosphere inside the aircraft was understandably tense as the Elizabethan attempted it’s third take off. There was a nervous cough, followed by a snigger in an attempt to break the tension.

"I don’t know what you’re laughing at, we’re all going to get killed here," Johnny Berry shouted, a right winger whose playing days would be cut short by the injuries he would sustain in the crash.

'Well if this is the time, then I’m ready,’ Whelan, a devout Catholic, responded.

Thain did what he had been instructed, increasing the throttle slowly. This time the aircraft reached 119 knots, but just as the Elizabthan’s nose pointed to the sky, the aircraft's speed suddenly reduced. The point to safely abandon the take-off had long since passed.

The plane carrying one of the greatest young soccer teams the English game had known crashed through a fence at the runway's end, hitting a fuel shed and house, before eventually coming to rest three hundred metres beyond the airports perimeter.

Twenty people were killed instantly, including Liam ‘Billy’ Whelan. He was 22-years old.

The Munich Air Disaster would eventually claim the lives of twenty-three people, including eight of United’s first team players, eight journalists, and three club officials. Among the officials was United’s chief scout Bert Whalley, whom Billy Behan had convinced to bring Whelan to United.

The crash was caused by a build-up of slush toward the end of the runway. As the Elizabethan had prolonged its take-off, it hit depths of slush other aircraft had avoided.

Pall of gloom

Liam Whelan’s body was brought home to Dublin. Thousands lined the streets of Cabra to show their support for the Whelan family and to pay their respects to their own Busby Babe.

In his autobiography, Johnny Giles, who was in the United youth team at the time of Munich, remembers travelling home to Dublin for the funeral.

I went up to his home in Cabra the night before with my father. The house was open to everyone on the night, and it was crowded. I saw Liam’s mother for a moment, but the poor woman didn’t know where she was. Everyone was shell shocked.

Dublin, like Manchester, was under a pall of gloom. It couldn’t be any other way in a city with such a football tradition, a city full of kids dreaming of playing for Manchester United.

Liam Whelan’s remains were buried in Glasnevin Cemetery.

In 2006, Dublin City Council renamed a Cabra bridge, just over a mile from his final resting place in Glasnevin, in his honour.

A tribute to his unique talent and untimely death. A humble memorial to one of the most gifted footballers the city has produced.