On Tuesday it was confirmed that a local businessman had intervened to save Dundalk FC, for this season at least. It's been a depressing and at times traumatic season for Dundalk supporters, especially considering the club's recent successes. And it occurs at a time when Dundalk is flourishing culturally. We visited Dundalk earlier this year to explore how the music and football co-exist scenes in The Town. Dundalk is a unique place with its own story to tell, but its football club is at the heart of everything it does.

Dundalk is a place at a confluence of influences. The biggest town in the Republic, it’s the county town of Louth, the smallest county. It also sits fifteen minutes from the border with Armagh, and therefore Northern Ireland. Though Louth is part of Leinster, Dundalk has a strong relationship with the neighbours to the north, most visible in their accent.

“It's a funny place, Dundalk, because it's sort of halfway between the two cities on the east coast,” Jinx Lennon said earlier this year. Jinx talks about this relationship in his music, with his 2020 album Border Schizo Fffolk Songs for the Fuc**d exploring the unusual dimensions of the border. You can see that Dundalk sits in a liminal space, with a distinctly northern influence about the place.

David Keenan feels a similar energy about the place.

“We’re nobody's children except our own because the southerners think we're up the north, and the north think that we're southerners, you know.”

Jinx also thinks that there is also a lot of influence on the town from Britain.

“Being on the east coast, it has a natural relationship with England, because a lot of transport and business coming into Dundalk would be through Greenore, which had links to Liverpool, and there were boats coming out of here 6 days a week from Dundalk Harbour to Liverpool,” he says.

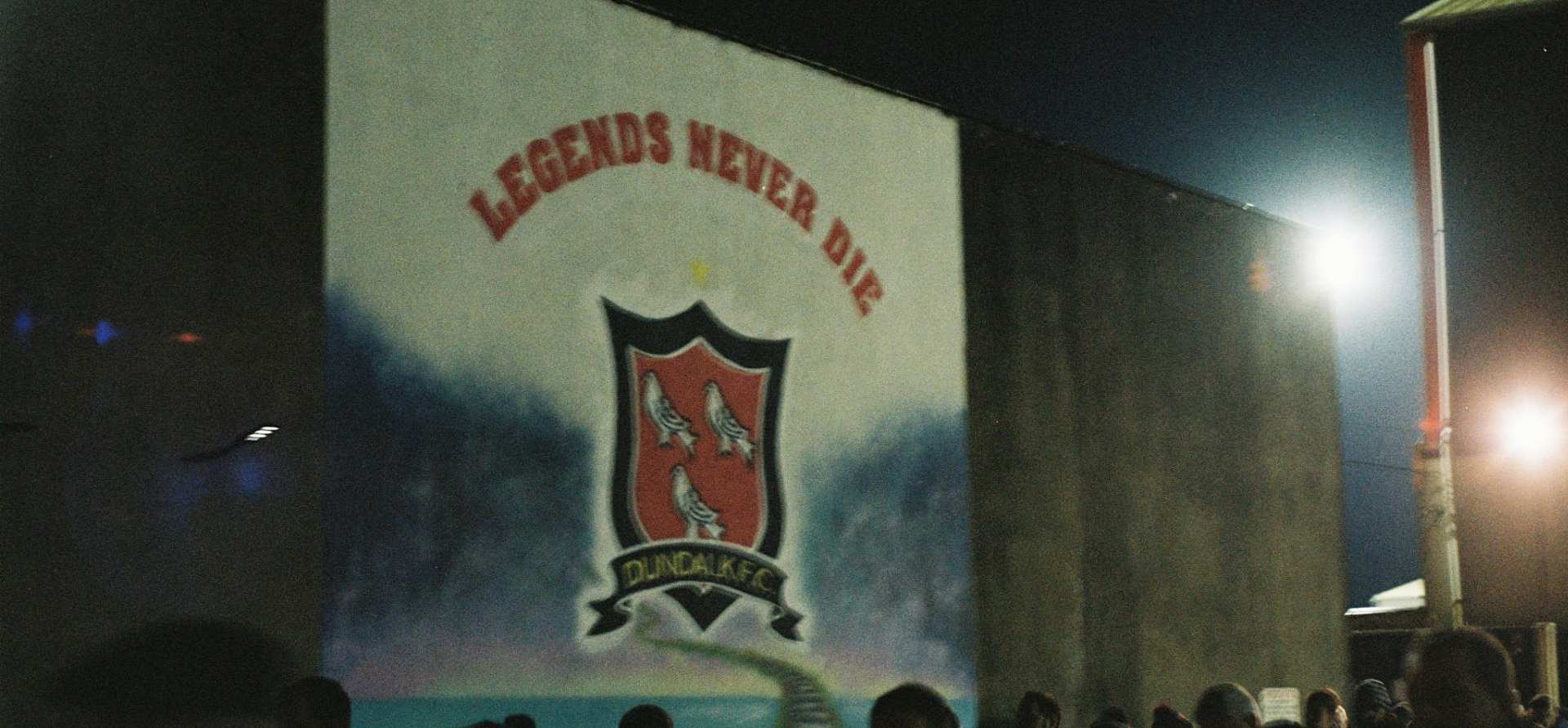

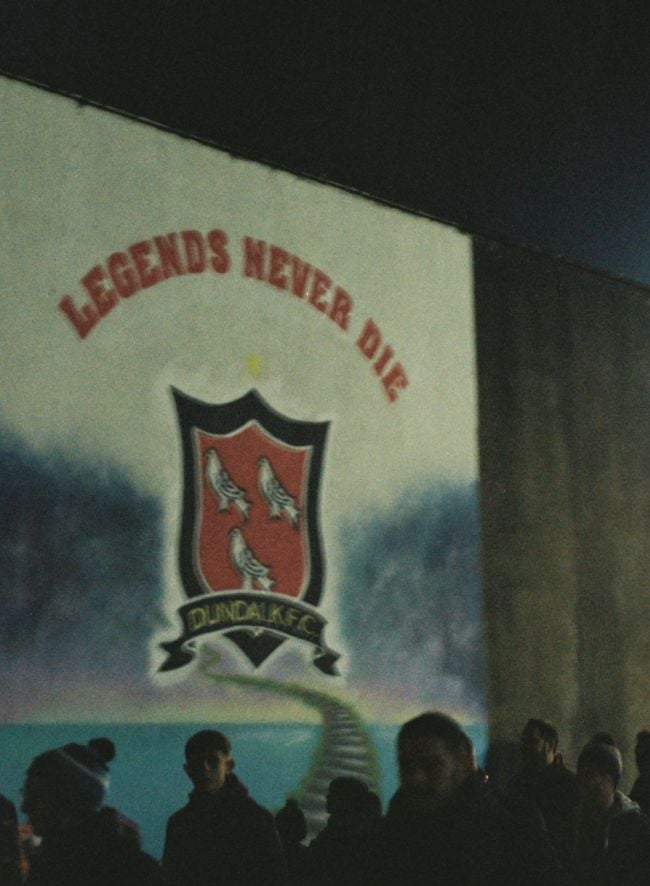

© Sean O'Mahony

Proximity to Northern Ireland meant that the British channels were readily available. “We were able to get the whole British TV thing, there was parts of the country that couldn't get the British TV, they were stuck with the RTE,” Jinx explains, “hurling and gaelic (football) is in the blood of people down the country and to the West, but up here British TV made it far easier for people to get into the culture and that.”

“I know it's an awful thing to say because it's a real Republican town, but there was a big appreciation for English football, there was almost a sort of Anglophile nature to the town. People were into English things here, English comedy, we were BBC'd up to the hills here. That was part of the culture, waiting for Grandstand for the football with Frank Bough.”

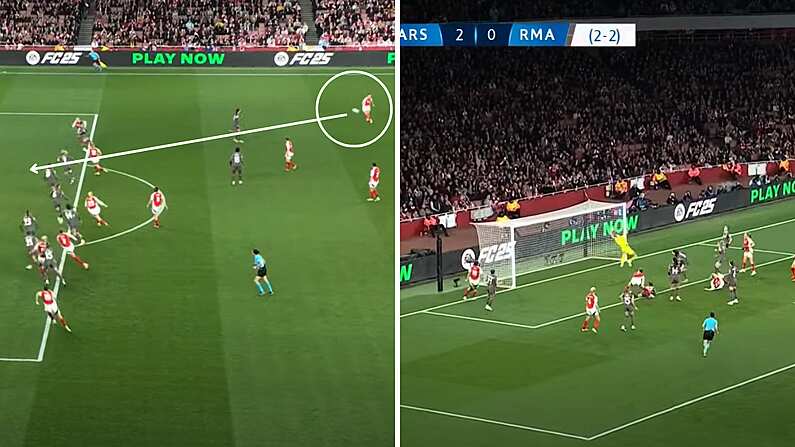

In Dundalk, soccer rules supreme. Dundalk FC is Ireland’s second most successful club, winning the League of Ireland fourteen times, including five times in six years between 2014 and 2019. However, this season the club has struggled. After the highs of a famous Europa League run under Stephen Kenny, then a sometimes surreal period of American ownership, Dundalk have found themselves on their third manager of the season and in the middle of a relegation battle.

Founded as a works team for the Great Northern Railway in 1903, they joined the league in 1926, and are the only surviving former works team to play in the league.

James Rodgers is a football journalist with The Argus, and he says that the industrial nature of the town shaped the club's identity.

”You're very near the railworks here, the railworks was actually the founding of the team,” Rodgers said, outside Oriel Park earlier in the season.

“Big industries over here, the Harp brewery was the big one for years very close to here. You had Macardle Moore, another brewery was a big thing, PJ Carrolls had a cigarette factory here. So that would have been the background to it. A lot of shoe factories as well, which a lot of the players would have worked in over the years when you go back to the history of the club.”

'Football football'

While Jinx isn’t a football fan himself, the influence of football on his life is evident in some of his music. He has three songs about football, some of them somewhat derisive, and one of them is a theme for a local football podcast. ‘Football Football’, from the Border Schizo album, is the most famous and derisive of them, and its music video was filmed at Oriel Park featuring a big football head. In the song, Jinx claims that football is only an excuse to “get away from the wife and drink your head off.”

It is clear from the song that Jinx is unlikely to be the biggest fan of the sport.

“I was a pariah at school because I wasn't into it,” he says, “and the thing was I used to try and get into football just to make friends, but I just had no inclination and then I sort of accepted that as time went on.”

Football was there to stay in Jinx’s life though, because being from Dundalk, you couldn’t escape it, not even if you played music. “Most of the bands that played here in the scene when I started off in the 80s were all football mad, and I'll tell you how bad it was,” Jinx explains.

“If we were doing a gig, we used to do the split gigs in this place called MJs which is on Park Street there, the whole thing about playing the gig was centred upon if Dundalk was playing that night. If Dundalk was playing that night, the boys we’d be playing with would obviously be going second.

Next thing, the door would open and the boys would be coming in chanting!

So it was all footballed up, that was it!

And the other thing was, we’d be trying to practise with bands, and they’d be all watching the World Cup!”

© Sean O'Mahony

The club is at the centre of pride in the town, and while other areas tend to ditch local rivalry to come together behind their county, town pride takes precedence in Louth.

“It’s a Louth thing nearly where, I think you travel anywhere and you say ‘where are you from’, people will say Cork or Limerick or Waterford or wherever, when you're from Louth, it's Dundalk or Drogheda and you know that's very important to people hare, it’s the sense out of identity,” Rodgers said. The support of the two town’s clubs being stronger than support for the county in Gaelic games seems to give some evidence to this.

“It would be very much a soccer town,” James says, “obviously Louth GAA unfortunately hasn’t had many successes [before recently', you go back to 1957 since an All Ireland win and back to the 1960s for a Leinster title, so even in local circles, the football club here means everything which is sort of more, I suppose, a British culture. There are a lot of GAA clubs in the area, but it wouldn't get any near the support of the football. It would consider itself a football town and is very proud of that.”

The football club holds an important space in the town, as a way of bringing the community together, and bringing money into the area.

“It just means something to everyone, I mean it's the heartbeat of the club I suppose. It's the one thing where, I think Dermot Keely said it best before, ‘when the town beats, the club beats and vice versa’, one sort of feeds off the other and it just matters so much. It's ingrained in the town, it's so important to the business community in the town as well and the money brings in on a Friday night.”

The club also recognises the importance of the community, and uses its platform to promote locals. “Michael Duffy, or Mickey Duffy's as we know him, he does the PA here, he would always have a section at half time dedicated to local artists. So it's always been something that the club has tried to push at the side, to promote local artists,” Rodgers said.

“Even in recent times you've had the likes of David Keenan, and he has a big song called El Paso which obviously talks about the experience of coming to a game on a Friday night, but he's played in the centre circle here.”

At Oriel Park

Everybody walks into Oriel through one entrance, which leads to the main stand. The place seems casual, there doesn’t seem to be anyone who cares about what ticket we have or where we can go. We chatted to one of the stewards, who had been working in Oriel for two years. Although he wasn’t too interested in football, he said that he enjoyed his job.

The Shed is where the ultras go at Oriel. Sitting opposite the Main Stand, it’s dark and cavernous, and it’s difficult to make people out. This is where the craic is. Any pics taken in the stand were too dark to even work for this story.

From here the chants ring, including usually the popular ‘C’mon the Town’. One thing that’s noticeable about the chants is their originality, while other clubs rehash English-style chants, everything I’ve heard in Dundalk is unlike anything I’ve heard before. You can tell that football has an important space in local culture.

David Keenan is from just outside Dundalk and went to school in the town. Because of that, he felt himself being in a in-between space where he wasn’t a culchie or a townie. However, going to Oriel Park as a teenager with his friends gave him a sense of belonging, and from that, he wrote El Paso.

“El Paso was my first fully developed song and, you know, funnily enough, in football circles now young lads are singing the song at the games,” he says.

“I've only come back to it, I suppose in the last year since I put out El Paso, I released that song, I got to sing El Paso before the Drogheda game last year so I kind of came into it again with that and reconnect it.”

The culture of football is something that David believes is strongly linked to music, and he includes it in his own music. His new single ‘Radiate a Smile, explores friendship, football, and human behaviours.

“Culture and music and sport and football have always been linked in terms of fashion and brands and subculture”

There’s a musicality and collective artistry in the stands.

© Sean O'Mahony

“You hear the chants in the Shed and obviously people go away and write them and then there's a group, it's a tribal thing, banging the drums and singing the songs, we've been doing it for thousands of years.”

This sense of collective effervescence that brings people together as a tribe also gives them a sense of belonging, David believes.

“In between people watching and slagging, a lot of people go there to just confide in their mates, you know, and it's kind of, it can be an aggressive violent atmosphere which gets people excited.”

Despite the place that the club has in the community, and the sense of pride and community that the club gives to the town, David feels that there is also a strong sense of neglect about the place.

“Oriel Park has been the focal point of the town for many many years, you know,” David says.

“It needs work, it needs investment, and I was there at the game against Bohs, and I noticed the away stand, there's lots of weeds growing. How do you expect a team to go out and get off the bottom of the table, and somebody isn't even pulling them weeds? So maybe there needs to be a cultural shift because it's such a successful team.”

At the moment of writing, Dundalk are now in last, sitting five points below biggest rivals Drogheda. Supporters of both clubs scrapped on the Oriel Park pitch as the DJ played 'Live It Up' by Mental As Anything. The football club has seen a major fall since they were last champions in 2019, and avoided liquidation thanks to the intervention of a local businessman. However, the music scene has risen dramatically since then, with more and more local bands seeing success.

“We're up there on the neck, you know, on our own,” David says.

"I can only say again the music in the last five or six years, look at the bands, Just Mustard, Mary Wallopers, Orwell ‘84, Jinx Lennon, you know, there's a real kind of, I don't know, just people out doing their own thing, being brave, sticking their chest out.”

The town of Dundalk is on the rise, and for years, its football club has been an important part of that rise. Its place in the community brings the town together, and its promotion of local artists has given them a platform in the community. Some of those artists are the best in the country, the Spirit Store is one of the best venues in Ireland, and the town has become a cultural hub.

But its heart will always be Oriel Park, and as they shout in the stands, “C’mon The Town.”