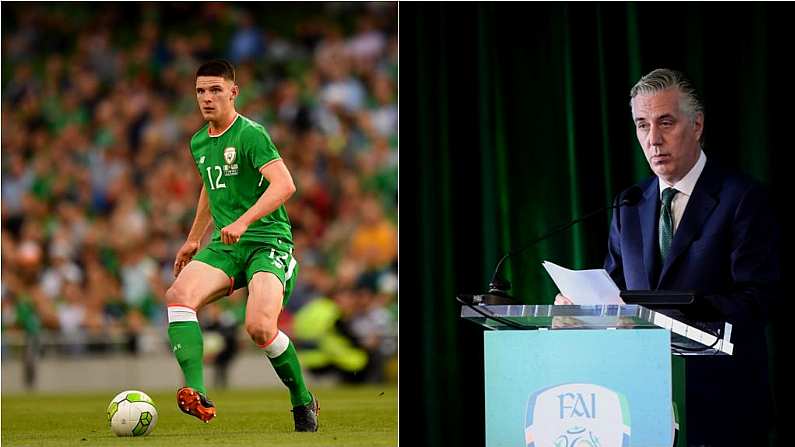

We are losing sight of the real issue here. Irish football has been thrown out of kilter with the news that Declan Rice is considering his international future. Born and raised in London, he qualifies to play for the Republic of Ireland through his Cork-born grandparents.

Rice has worn the green jersey at every level since U16, and already has three caps at senior level. As all of his senior appearances have so far come in friendly games, he is still eligible to change his international allegiances to his native England. He looks likely to do just that.

The news has been met with disdain from Irish fans. How can a player who was seemingly committed to the Irish cause be thinking of turning his back on the country? Current and former players are even getting involved in the discussion.

Rice is a player that is full of promise, and his loss would sting. Ireland can ill afford to lose players of his quality. The rule that allows for his change of heart can be debated, but that is not the point. Just like the Jack Grealish situation, this has the potential to dent the hopes of future Irish teams.

And therein lies the issue. The future of our national football team can be derailed by the choice of two young English players to play for their home nation.

Both are good prospects, but neither are likely to be world beaters. They are players that Ireland had little to do with developing, and in some regards simply fell into our laps.

Fans may feel a sense of betrayal due to their decisions, but that is to ignore the big problem here: the struggle we have in developing our own players. The Rice and Grealish cases are extreme examples of this, but it is true in a much wider sense.

We are completely dependent on English clubs to develop our best prospects. That is the case even for those born on these shores. Most of our top young players move to England at around 16-years old, and from there on they are at the mercy of the cutthroat world of professional football in the UK. For far too long the FAI have been happy to go along with this dynamic, our footballing destiny in the hands of an exogenous force.

This may have worked for us in the past, but its effectiveness is wavering. The globalisation of the Premier League has resulted in an influx of talented players from all over the world. No longer are English clubs limiting their recruitment to the UK and Ireland as they were for decades previously.

There are now less opportunities for Irish players at the top level of English football, and that filters all the way down to academy level. While it was never a certainty that a kid making the trip to England would make the grade upon their arrival, the chances are now slimmer than ever.

Our players are being pushed further down the totem pole of English football, with the number of Irish plying their trade in the Premier League at a worrying low. Our young footballers are now being targeted by Championship clubs, and this is having an effect on our national team.

By and large, a certain type of player is required to play in the Championship: fast, strong, physical, take no risks. Smaller skilful players are often left on the outside looking in. This is having a profound influence on the type of footballers we are currently developing. A look at Martin O'Neill's side can tell you why this is a problem. They are not likely to lose many physical battles, just as they are unlikely to play a type of football that is appealing to the eye.

The figures on young players moving to academies in England do not make for good reading. Only a minuscule percentage make a career over there. The rest return home, often disillusioned with the game. Perceiving themselves as failures, they drop out of football altogether. So much wasted potential.

The model in this country has been simple. Our best young players would play schoolboy football, most likely in Dublin. Then they would move to England at the first opportunity. There was a degree of separation between our top prospects and the League of Ireland, as most of the would never have any affiliation with a club from our domestic league.

As has often been the case, The League of Ireland was an afterthought for our national association. John Delaney once described the league as 'a difficult child for the organisation', and that attitude is still largely present.

While the league has been under-utilised and largely ignored as a potential breeding ground for the next generation of Irish talent, this is finally changing. As part of FAI High Performance Director Ruud Dokter's Player Development Plan (published in 2015), all League of Ireland clubs will now field teams at U15, U17 and U19 levels. National leagues have been set up, with the aim of having the top prospects in the country compete with and against each other on a regular basis.

After decades of neglect, the FAI are finally taking a hands-on approach to player development. We have seen the effects this has had in other countries. France opened the doors of Clairefontaine in 1988, and a centralised approach to player development took hold. Many of their star names over the last three decades would be coached here, and its legacy lives on via two World Cup wins.

Convincing our top young prospects to stay on these shores for a longer period of time is altogether another matter. How can we assure them that the best thing for their development is to stay and play for an Irish club, not to move to one of the big boys over the water?

Of course the best players will still go at some stage, and this is what is ultimately best for Irish football. We want our players to play at the highest level possible. But by delaying that step for a little longer, one would hope that there is less chance of their experience meeting an undesirable end.

We have seen a number of players make the move to England after a good stint in the League of Ireland. Graham Burke and Seán Maguire are just two of the recent examples.

Getting to England is the end goal, but it should not be the starting point for these players' careers. It should not be the be all and end all it once was.

There is no doubt that the FAI had become complacent in their dependence on English clubs to groom our best young players. The question now is, have these changes come too late? It will likely be a number of years before we see the effects of the Player Development Plan, if we see any effects at all.

We are so far engrained in this dependence that it will take a monumental shift in mindset for the dynamic to change. The Declan Rice situation just drives that point home. The future of Irish football looks uncertain, and that has nothing to do with Declan Rice or Jack Grealish.

Before we place the blame on the door of a 19-year old trying to do what is best for his own career, perhaps we should take a look at what is happening a little closer to home.