It is plainly obvious that our footballing destiny has long been in the hands of an exogenous force. That is a reality we now need to face head on.

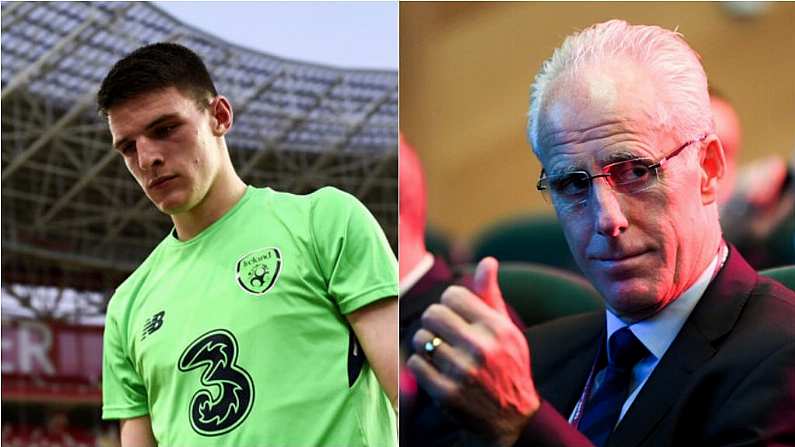

Declan Rice no longer wishes to pursue his future in International football with the Republic of Ireland. In a saga that has dragged on for months, the three-cap international today confirmed his desire to play for England. It is a big blow to Mick McCarthy, losing a player who clearly possesses vast potential.

It could be argued that this news could not have come at a worse time. Under the guidance of a new manager, Irish football fans had regained some of the optimism that had been lost during the tail-end of the Martin O'Neill era. To have a player of Rice's age profile be the face of this new era seemed an ideal fit.

The problem is, players of his quality are all too rare in the current squad. It is unlikely that this decision would have been as impactful if it had taken place in eras gone by. There was a time when our team was packed full of upper tier Premier League talents, but those numbers have steadily dissipated in the past two decades.

In summary, we no longer produce high quality players. The fact that Rice is someone who was not linked to youth football in Ireland in any manner prior to being called up at U16 level only drives this point home.

So where have all the great Irish players gone, the Roy Keanes, the Ronnie Whelans, the Paul McGraths? This issue can largely be boiled down to our reliance on the English football system, and all of the perils that comes with that approach.

The fortunes of our national team have always been largely tied to what goes on across the water. We have benefitted from the 'granny rule' more than any other nation. Some of our most successful players of the last four decades have been recruited via this method. It could be argued that this comes down to the patriotism that is associated with having an Irish heritage, but what cannot be debated is that most of these players have fallen into our laps by what could be termed as 'blind luck'.

The FAI, and various Irish managers, cannot be faulted for following this method of recruitment. They would be foolish not to cast as wide a net as possible. The Rice situation is a swift reminder of the perils of such a policy, how sinking resources into a player who may not necessarily be all that committed to Ireland can come back to bite you. But that is the nature of the beast.

There is something that is far more worrying, and will have a much greater say on the long-term health of our national team. Recruiting second, or third, generation Irish based in England is one thing, but we need to take much better care of the young players that originate from these shores.

We depend on English clubs to nurture our brightest young talents, we always have. The same model has been followed for as long as youth development has been a focus in football. Our best young players travel to England at the age of 15 or 16, and from there on they are at the mercy of the cutthroat world of professional football in the UK. The FAI had seemingly been happy for this dynamic to continue, with our own indigenous structures becoming increasingly neglected as a result.

We have seen our next great hope, Troy Parrott, go down this exact route. While it appears to be going well for him thus far, many have not been so lucky. We have to take responsibility for our top young players.

While it worked for a number of years, there has been a failure to react to the changing landscape of world football. The Premier League is now a global league. While previously occupied almost entirely by players from the UK and Ireland, the last three decades has seen a major shift.

Globalisation has taken hold, movement of footballing labour has increased, and the playing pool from which English clubs recruit their assets encompasses every corner of the globe.

That has extended all the way down to academy level. While in the past Irish youngster who travelled to England would face the best native youngsters, they now compete with players from all over the world. The chances of making a first team breakthrough has never been slimmer. Irish players are pushed down the English footballing pyramid as a result.

If we want to make improvements to our own playing pool, we made to take responsibility for the development of our young players. We cannot, and should not, depend on England to do what we should have been doing for a number of decades now.

We have moved in that direction in recent times. All League of Ireland teams now field teams at U15, U17 and U19 levels, with a national league being introduced to ensure our top prospects play with, and against, others of a similar level. We are moving towards having professional academies in the Republic of Ireland for the first time in our history.

Our best young players must be given the opportunity to play and develop without leaving their families and moving abroad before they are even legal adults. We can only delay their departure by offering a system that will maximise their potential, a genuine alternative to the lottery of English academies.

The best players will still go to England, or perhaps further afield, at some stage. And that should still be the goal. We want Irish players playing at the highest possible level, and that platform still must be sought beyond these shores. But they should be given the opportunity to mature, as people and as footballers, before they do so.

Declan Rice's decision is a major blow, and that is partly our own doing. We need to have the structures in place to ensure that losing one young Englishman does not greatly impact the future of Irish football. The process has started, now it must be accelerated.

Until we address the lack of balance in our youth development policies, our future prospects for success will continue to dwindle. That is not Declan Rice's fault, and is something we need to remember. We got ourselves into this hole, and now we need to get out of it.