And so ends the strangest of years. 2020 will live on in infamy for the rest of our lives. So much has happened in the last 12 months, and yet, at times it felt as though nothing was happening at all.

Our annual look back on our articles on Balls.ie reveals a year filled with frustration, anger, and disappointment, but also one full of joy and inspiration.

Over the course of the week, we are sharing some of our favourite pieces from the maddest of years to relive some of what you may have forgotten or missed in 2020.

You can read more of our favourite pieces here.

*******

In early May, Radio Kerry had a segment picking an XI of the best footballers to emerge from the Kingdom. It was one of those ideas scribbled in a producer's notebook, destined for a humdrum Sunday in December when GAA was in hibernation. But Covid-19 has ensured these are sleepy days for every sport.

The team was a mix of those who made their careers in the League of Ireland and the sub-Premier League tiers of English football. They were good players but none who had made it to the top.

Kerry is a county obsessed with the round ball but it is Gaelic football rather than association football which dominates. Tony O'Connell, who won two caps in the 60s, is the only Kerryman to play for Ireland, and he grew up in Dublin.

In midfield, there was a curious selection: Michael McElhatton. As bell-ringing names go, only with the most nerdish of Irish football aficionados would it make a dang.

Search the internet for him and information is scant, bar for which clubs he played and the years. Indications that he was born in Kerry are restricted to Wikipedia and websites like Soccerbase.

A trawl through the archives of the Kerryman newspaper and there are more mentions of the actor with the same name than the player. There is just a single acknowledgement of McElhatton in the paper and that was a decade ago in a similar exercise to Radio Kerry's. "No photograph of Michael McElhatton" was a postscript to the piece.

Considering he had made it on an XI of Kerry's best players, it was strange that there was so little information about his links with the county. The possibility that his connection was bogus arose; maybe there was a Wikipedia editor playing the long con.

That thought was mistaken. In 1975, Michael McElhatton was born in Kerry.

This is his story.

* * * * *

The end hurt more for Michael McElhatton than it did for others. The athletic ability and skill it takes just to make a living from football - no matter at what level or for how brief a period - is hugely underestimated. McElhatton did it for a decade.

Just getting to that point was tough, not just because a player has to work hard to be noticed by coaches and managers. He had other obstacles. He had to endure more.

A certain amount of good fortune is required for a player to reach their potential. He had the potential - many saw it - but just not the luck. If McElhatton had bought the winning lottery ticket in the 90s - he must have felt like he had it in his hands at times - he'd have been pickpocketed on the way home.

"I went through quite a lot as a young kid," McElhatton tells Balls.

"When I made it, it was 100 per cent more achievement than other young lads."

The man, now in his mid-40s and living in Bournemouth, was born in Killarney. His mother was from Cookstown, Co. Tyrone and his father was English. They'd moved to Kerry not long before his birth and ran a fruit and veg shop in the picturesque town.

The family departed Killarney when their son was two-and-a-half and then bounced between Derby and Belfast. They left the North at the height of The Troubles when McElhatton was six.

"They moved to Derby, where I lost my [Irish] accent at the age of seven or eight," says McElhatton.

"The biggest thing that I hate about myself is my accent."

He played for Derby County until 14 when his mother headed to Bournemouth with his stepfather, who had arrived on the scene seven years earlier.

Harry Redknapp signed me. They wanted me to sign before that. I didn't bother, I went straight into work because £35-a-week in those days wasn't a lot of money as a YTS (Youth Training Scheme player).

I then joined as a second-year YTS. It was still £35-a-week with £10 travel and expenses. I made my first-team debut at 17.

The lower reaches of Division Two (what is now called League One) was Bournemouth's station during McElhatton's time there. After Harry Redknapp departed in the summer of '92, he spent two seasons under Tony Pulis, who had been a player/coach at the club. The Welshman left ahead of the 94/95 season and was ultimately replaced by Mel Machin.

That season would become a famous one at Bournemouth, the first of their 'Great Escapes'. By Christmas 1994, they had just nine points in the bank from 21 games; falling through the trap door to Division Three looked inevitable.

"I went through a time at Bournemouth where I played centre-half for a while in the Great Escape year at Bournemouth," says McElhatton.

"I scored two important goals that kept them up that season.

"Mel Machin, when he first came along, I was the next Beckenbauer to him. I was the best thing since sliced bread. He said [good] things in the paper [about me] and I was very popular at Bournemouth because I was a local lad in a way."

Though his star rose as a player, his standing with Machin did not.

In October 1994, Bob Hennessy wrote in the Sunday World that after watching the 19-year-old play against Chelsea in the League Cup - then in its guise as the Coca-Cola Cup - he'd "quietly tipped off" Jack Charlton about McElhatton's Irish eligibility.

Dave Hannigan noted in the Sunday Tribune a few weeks later that having been informed about McElhatton at the Airport Hotel before the European Championship qualifier against Liechtenstein, the Ireland manager responded with something along the lines of "It's a bloody striker I'm looking for". Still, Jack made the call.

McElhatton was not the only Irish player at the club. Sean O'Driscoll - who won caps for Ireland in the 80s was there - as was Matt Holland.

O'Driscoll gave his fellow midfielder more encouragement than anyone else. Later in his career, when he became Bournemouth manager, O'Driscoll tried to re-sign McElhatton.

"I had a choice of playing for three [countries] at the time," McElhatton says.

England, I said 'No chance' to. Gerry Armstrong from Northern Ireland, he came over, watched me in a few games and wanted me to play for them, I said no.

Then Big Jack, I had a conversation with Jack Charlton, he said he'd like me to play for the Irish schoolboys, which I agreed to do.

I spoke to him at Bournemouth in the manager's office. He had some people come and watch me. He knew that Northern Ireland wanted me. I said that I would only ever play for the Republic. The rest is history.

McElhatton never got to play for Ireland. He was called up to the under-21s but the first of what would be a series of crippling knee injuries prevented him from wearing the green jersey.

It came at a bad time not just for his international prospects but his career in general.

"Chris Kamara did say live on TV that I was the next Roy Keane. I had a few people saying that they didn't understand why I wasn't in the Premiership.

"Everything was in the paper about me getting a call from Big Jack. It was all highlighted. Then Southampton came in for me.

"You can imagine my frustration that I'd just got picked for Ireland, I was close to a £500,000 move to Southampton at the age of 19, and then I got a bad injury."

It was a medial ligament which McElhatton damaged. These days, it's an easy fix. Back then, medical science was still rubbing two sticks together to spark a recovery when it came to knee injuries.

"In a way, I got let down by the manager in Mel Machin," says McElhatton.

"I just felt that Bournemouth weren't protecting me as a young player.

"I went to see a specialist and he said, 'He'll be fine, he'll be fine, just put him in a cast for six weeks'. They didn't give me a scan and, of course, I came back from the injury, played a couple of first team games; I think against Crewe Alexandra it snapped really bad [again].

"I went, 'Something's not right. I told you it's not right'. Of course, they wanted to quickly play me again because the money was there on the table waiting for me to go.

"Mel Machin's went, 'There's nothing wrong with you. I've been told'. Then I had to get the PFA involved, it went further. I fell out with a manager, which at the time ruined me as a young lad.

"I felt he'd destroyed me and the PFA didn't do me any favours. I know they had to help me out but when I went for the scan finally and it showed what was wrong, it was never going to heal. Because I went behind the manager's back to get all this done, we had a falling out.

"While I was a sub, fans were screaming to get me on, to play me, but Mel Machin never did it. He never did it for a long while. I realised I was never going to play."

'Kevin Keegan, while he was at Newcastle, said he was interested'

McElhatton knew he had to pack his bags when, with Bournemouth amid an injury crisis - and after he had played the game of his life for the reserves, scoring a hat-trick - he didn't get the nod from Machin.

Still a teenager, he didn't have anyone advising him. A friend said he'd found a manager willing to help him out. That was Mick Wadsworth who'd become Scarborough boss in the summer of 1996.

Scarborough would be a drop down to Division Three but also an escape from spinning his wheels under Machin. He joined initially on loan and then permanently.

"There were some players at Scarborough who made me feel like a million dollars," he says.

"It made me sign. There was Andy Ritchie who had been at Man Utd and Oldham. Ian Snodin, his brother played for Everton. They made me feel so welcome and it was a breath of fresh air really.

"I had a great season there. People were interested. I've got a paper clipping of Kevin Keegan coming down while he was at Newcastle saying he was very interested in me.

"In a way, I probably shouldn't have gone to Scarborough - I should have waited - but I was so depressed at a club where I was wanted by the fans but not by the manager."

He spent two years at Scarborough, with the club finishing mid-table in his first and doing far better in his second.

"I had a few offers to go to Wimbledon, and Sheffield United under Neil Warnock, because we played them in the FA Cup," he says.

"They didn't let me go because we got into the playoffs. The worst thing happened, we didn't win in the playoffs and it was too late because clubs had gone and got the players they wanted. Then Scarborough told they couldn't afford to keep me because they didn't go up."

In the summer of 1998, McElhatton joined a club which had only come into existence six years earlier. 1992 saw the merger of Rushden Town and Irthlingborough Diamonds. Max Griggs, the owner of shoe company Dr Martens, was the man behind the union. Rushden and Diamonds was the married name.

By 1998, they had been in the Football Conference (now called the National League) for two seasons. With Griggs as their backer, the club had money to burn. Former England international Brian Talbot was manager and he'd tabled what McElhatton calls a "crazy bid" while he was at Scarborough. That was in the then 23-year-old's mind as a free agent that summer.

"Rushden and Diamonds were like a mini Man Utd," he says.

There was an unbelievable team. They were throwing out better money than the Championship.

I thought about what I should do and I risked it, I made that phone call to Brian Talbot and he told me to come down and have a look. It was better facilities than most clubs in League One and the Championship.

He said he'd give me a relocation fee, you get can this house. It was mad offerings what they did for me; when you've got a wife and a newborn baby and she had a boy at the same time, not taking it is a risk.

As soon as I signed for Rushden, I had quite a lot of phone calls saying, 'Please don't tell me you've signed'. It was quite off-putting that a lot of clubs saying they would have signed me.

In his first season at Rushden and Diamonds - where they finished fourth and failed to gain promotion to the Football League - McEhlhatton played a conservative midfield role.

"Brian Talbot made me into a very good player. He signed me and said, 'Do you know what? You remind me of myself'. That's a man who's played for England, Arsenal and Ipswich.

"He basically bred me into being him. He made me into one of those defensive midfielders, like a Kanté at Chelsea. He wanted me to do it and I did do it. I got Player of the Year that season, Players Player of the Year; it was like something that I thought he'd done right for me.

"It was just the second season that I went, 'Do you know what? I'm better than this. I can score'. I just started scoring for fun and realised that was going to be my game.

"He knew I was a leader. They all knew that I had that in me as a player, that [defensive midfield] role. That's why a lot of clubs were interested in me, doing that role.

"It was pre-season that I scored some crazy amount of goals in friendlies. I went into him and said, 'Look, give me an opportunity. I've got another player beside me who can do the holding role. Let me go on'. It worked. I did like a Lampard role."

McElhatton flourished in that more adventurous post. Goals flowed in the 1999/00 season with an ease reflected in his demeanour on the pitch: the jersey was untucked and the collar up. Scouts were attending games to watch him. "I did believe finally that I was going to get back into the Irish squad and finally play," he says.

In 96 appearances for Rushden and Diamonds, McElhatton scored 22 times. It was strike rate which had clubs higher up the ladder interested, including Preston North End under David Moyes.

"There were a lot of clubs making big money bids for me but the trouble was Max Griggs, he was having none of it," McElhatton says.

"He didn't want the money. He just wanted us to go up. He was turning deals down."

With the season entering the final straight and Rushden in the promotion hunt, disaster struck when McElhatton's knee buckled. He got back on the pitch but would suffer the same injury twice more.

"When it first went, it was basically a shock to us all - the physio, the manager," he says.

I was flying and no one thinks anything like that can happen.

My determination, I thought I'd get back there with rehabilitation - 'I'll do whatever they say'.

They should have given me the proper ACL operation first. They stapled my cruciate together. It was a new design but it shouldn't have been done with an active sportsman.

It was a rush job by Brian Talbot - he wanted me back as soon as possible. It went quite quickly [again]. After it going that time, then they repaired it the way it should have been done the first time. Then it took me a whole year of gruesome rehabilitation. That's when I came back and it was like, 'I've done it!'

I was out nearly one year with the first injury, came back, played nine games. It was frustrating because I only had to make ten games and I'd get all my bonuses. It was a big deal.

The mad thing about it, I had that serious injury and they gave me a four-year contract after I got the injury. They didn't just dump me. They looked after me and said, 'Look, we'll get you through this. We'll get you back'. I think they realised that they might have messed up a move that I should have had.

After finishing second in the season where McElhatton got injured, Rushden won promotion to Football League in 2000/01.

"I went through a lot of traumatising myself, seeing the club progressing while I wasn't playing," he says.

"They went out and bought more players, bought themselves a couple of titles. It was like I missing out on everything. I was missing out on the move I should have had. Every time there was a big move [on the cards] I got injured.

"It was all going through my head but I was determined to get back, which I did. I started playing well.

"I went to Chester City [on loan] to play for Mark Wright from Liverpool. I scored some crazy amount of goals to keep them up. I came back to Rushden, played in the league, and the injury went again.

"The third time it went, that was where the specialist said, 'Look, I'll repair it but you're not playing again. There's no way you can ever play again. You'll end up on crutches or in a wheelchair'."

McElhatton's tough childhood - the details of which he doesn't want to go into right now - was an ocean he had to sail before reaching his football career. That he got there and found he had a leaky boat unable to take him any further was hard to take. During the injury layoffs of his career, McElhatton had turned to alcohol and drugs to cope with the frustration. He did the same when he had to hang up his boots for good.

"It took a while to realise that my dream was gone," he says.

"When I had to quit. I couldn't talk. I think I cried for about a week. I couldn't stop. I went through a spell where people didn't realise that football meant more to me than most people because I had to fight hard for it.

"Truthfully, I struggled. I really did struggle. I've been told that I should write a book. Honestly, my childhood to finishing, to what happened afterwards - it was crazy.

"It was very difficult to take. I moved down to Bournemouth with the money I made, bought a lovely big house and then I got a divorce.

"I did go through a real bad spell. I went in to drink, drugs. I was gambling. I needed the fix of winning things. I became not the person I wanted to be. I was hiding everything from my daughter when I saw her. People never saw it in me because I hid everything well. I was really, really bad.

"[Drinking and doing drugs] was happening through my career, through the disappointment. When things were going well, I was sky high because I realised I deserved it for what had happened. Then when an injury would happen, it would all come flooding back. It's what happens in people's lives if you've had a trauma as a kid. It comes back at the worst time."

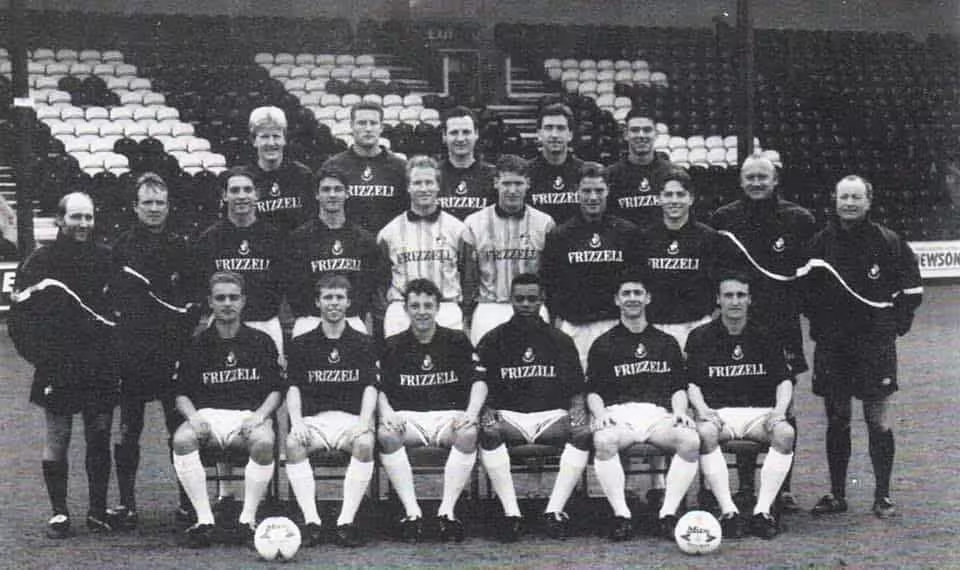

Bournemouth 1994/95 squad. Michael McElhatton fourth from the right in the middle row, standing next to Matt Holland. Picture: Steve Jones/Facebook.

There is a happy ending to this story, or certainly one on the tracks to that destination. McElhatton, who worked as a plasterer following retirement, is now a site manager for Apollo Building Services, constructing specialised rooms in hospitals for MRI and CT scanners.

He's in a good place, has a good relationship with his daughter and has plans in place to move back to Kerry where he hopes memories won't haunt him.

"I've done well," he says proudly at how he's turned his life around, while also knowing that he's not over the finish line yet, and may never get there.

"I fought for everything. It must the Irish in me. I've just moved on, got better and better.

"I'm living in Bournemouth now. My daughter lives around the corner. I see her as much as I can. I have a really lovely relationship with my daughter which is the thing that got me through after the end of my career. If it wasn't for her, I probably wouldn't have carried on.

"The truth is - my Irish family know it - I'm moving back to Ireland soon. I would say within one to two years, I'm planning to be in Killarney.

"This has been my dream. I've been back to Killarney and have been down south a few times with friends and family. I'm drawn back there, it's where I've got to be. When I hit the turf of Ireland, I'm happier than I've ever been; I realise it's for me.

"My daughter is going to be 21 soon. I've her setup as much as I can and then it's my time.

"What I went through in my life, I feel there's only one place I should be and it's Ireland. I've not had the best run over here.

"I've had such a hectic life. I think if I go over there, I'll have a bit of peace."

Top photo credit: Martyn Bishop/RDFC1992.com