The life of the Superbowl winner is supposed to be measured in script. Be it abstractly in the length of their contribution to the 'history books', or more practically on websites, in dusty records books, on photo frames and plaques. If playing is ephemeral, then winning is eternal.

George Visger is a winner. His emblem is the 1981 Superbowl with the San Francisco 49ers, and his life is measured in script. Exhaustively.

10.05 - Spoke to Leslie about tutoring her kids.

10.20 - Called my wife to visit the kids.

10.45 - Arrived at Home Depot on my way to visit the kids. Parked on the southside of the building, nine rows from the East, under the first streetlight.

This is history written by the winners, but in real time: Visger has to log every single detail of his daily life in a notebook, down to where he parked his truck.

David Remnick wrote in his masterful biography of Muhammad Ali that the "history of fighters is the history of men who end up damaged". It's the same in the NFL. George Visger was a sixth-round draft pick in 1980, and ended up playing with the San Francisco 49ers. He has since developed Hydrocephalus - excess fluid on the brain -and has had nine brain surgeries, countless seizures, more than 250 Hyperbaric oxygen treatments, struggles with anger management along with developing insomnia, dyslexia and being diagnosed with frontal lobe dementia as a result of multiple concussions.

In the last six years, his memory has cost him his business, his home, and his family. George Visger the businessman would forget to bill certain clients, while double and triple-billing others.

George Visger the father would rent the same movie three times a week, and forget to turn up to his son's basketball games.

George Visger the husband would exasperate his wife Kristi by missing meetings, and by getting angry when he remembered the appointments she called to remind him of. She developed irritable bowel syndrome. It all caved in.

He now lives alone, in a shabby attic above a hyperbaric oxygen clinic. He sleeps in a sleeping bag on a single mattress, and has for company a lamp, a hot plate and the spoils and costs of victory: an '81 Superbowl ring and thousands of small, pocket-sized notebooks. These survive as emblems of the appalling daily battle he is fighting desperately not to forget. In this Wasteland, memory is the desire.

We spoke over a Skype line at 8am California time on Sunday, having set up the interview the Thursday previous. Ahead of the interview, my name adorned a post-it note on the dashboard of his truck for three days. Reminders went off on his phone on Friday, three times on Saturday (midday, 7 pm, 11 pm) then at 5 am, 6 am, 7 am, 7.15am, 7.30am, and 7.45am on Sunday.

In order to maintain concentration during our interview, he needs to lean forward, touching the tip of his nose against the screen of his laptop. He keeps his eyes closed, opening them only to jot down my questions in his notebook, in case he forgets them mid-conversation.

He tells me he is "fighting not to lose his mind".

I ask how he deals with that.

It's been.... it’s...beyond my comprehension I'm at this stage of my life. I'm 58 years old, I think.

******

Visger's childhood ambition to be the next Jacques Costeau was superseded at the age of 11 when he began playing football.

He "busted his tail", as he puts it, but he made it: drafted by the Jets but played in San Francisco. But when a franchise signs a player, they also take custody of the dream. And they can let that mature however the hell they want.

Visger suffered multiple concussions on his way to the NFL. His first diagnosed concussion came in his third year of Pop Warner football, and suffered numerous undiagnosed concussions in his three years as a defensive tackle with the University of North Carolina. The most serious came in the NFL, on the first play in a game against Dallas, in 1980.

First play in the first quarter, I get ear-holed on a Dallas tight end trap. They don't block the defensive tackle: they let you get up field and they bring the tight end into motion, and he catches me right in the temple. Major concussion, first quarter. I don't remember that game. Before the next game, a week and a half later, the trainers and doctors laughingly told me that I went through nearly 20 smelling salts during the game to keep me on the field. I never missed a play, I never missed a practice. It was a joke to them.

Six months later, Visger began to feel seriously unwell. The 49ers gave him blood pressure tablets, in a gross misdiagnosis. At home after one training session, Visger went through hell: the headaches were shattering, the projectile vomiting was relentless.He lost his hearing and eyesight intermittently, and his right arm began to curl unprompted across his chest.

The next day, he confronted the 49ers' medical team.

Don't tell me it’s only high blood pressure, my arm went paralysed last night'. He rolled his eyes, and said 'sit down on the table'. He takes his little light, shines it in my eye and said, 'Oh my God! Your brain is hemorrhaging.”

The doctor told him to get in his car and drive an hour to a neurologist in Stanford. Having been told to drive, and with a limited knowledge of such injuries, Visger assumed it wasn't too serious. He ended the day recovering from emergency brain surgery.

Repeated head trauma had caused Visger to develop Hydrocephalus, which is the build-up of excess cerebral spinal fluid on the brain. The tiny ventricles in the brain - holes about the diameter of a pencil - drain this fluid, but in Visger's case, these ventricles had become blocked by scar tissue from concussions. This causes the build up of fluid, which began crushing his brain like a can in a clenching fist, and will cause death if the fluid is not released.

Visger had what is known as a VP Shunt, a procedure which allows this fluid to be drained away.

Months later, he returned to the 49ers, with the hopeless promise of a new helmet to protect his brain to allow him to keep on getting hit.

While training to get fit again, Visger endured a time he know refers to as the "dark months". Previously impeccably-behaved, Visger was arrested three times in the three months following his brain surgery. He would be out, having wine with dinner, or a couple of beers, and then.....what? He would be staring blankly at a jail cell wall, wondering how the hell he got there, hearing stories of how he was tearing up bars and getting into fights.

One minute I'm at a restaurant or bar, and the next thing I know it's six, eight, ten hours later and I'm standing in jail, with no idea how I got there. I'm not passing out and waking up, I’m standing there asking, 'what the hell?'. They'd release me in the morning and I'd had to go ask 'what the hell was I arrested for'. It was crazy.

Luckily, I never hurt anybody seriously. One time I was arrested for being drunk in public, driving under the influence, resisting arrest, I guess I fought the cops, and being under the influence of narcotics. They thought I was smoking PCP as I was violent, and my pupils were dilated.

They gave me a blood test in jail, I don't remember that. When I came out the seizure and saw a band-aid on my arm, I had no idea what I had done. I had to hire an attorney, and went to court and people were telling me I was doing things that I didn't know I had done. I had no idea whether I had done any drugs that night.

Visger got the explanation of this behaviour in May 1981, four months after the Superbowl. A neurologist gave him two beers and deduced that they were sending Visger's fragile brain into seizures. He hasn't had a drink since. This revelation came after another period of absurd tumult. Holidaying in Mexico with his brother, Visger collapsed after drinking a margarita. He was flown home in a coma.

A second emergency VP Shunt followed, from which Visger emerged for just ten hours, before collapsing again. On May 22nd 1981, at the age of 23, George Visger had his third emergency brain surgery in ten months and was given the last rites.

The causes behind his slipping from coma to coma was the shunt: it kept failing and plugging up. In order to keep draining the excess spinal fluid, surgeons have inserted a tube into his brain that comes out at the skull, and goes in under the skin at the back of his head, where there is a twelve -inch incision. There is also a pressure valve under the skin behind his right ear, and from there, there's a tube that goes under his skin, through his chest, and into his abdomen, constantly draining spinal fluid.

After the third brain surgery, Visger has no memory of the next 18 months. He says he "just forgot to return to the NFL", and went to work as a labourer for his brother, making ten dollars an hour. To get by, he spent his nights as a nightclub bouncer making $12 an hour. He did that for years while battling creditors, as the 49ers denied he was injured playing for them and left him with the hospital bills. He was forced to sue for Workers Compensation to get his medical bills paid, and finally won his case in 1986, after which he returned to college to finish off the Biology degree he had put on hold for the NFL.

While at college, his VP shunt fell out six times. Each time, he was rushed for emergency brain surgery in order to drain the fluid on the brain, and to restore the shunt. Eventually, he persuaded his neurologist to give him what he calls his "brain drain" kit. When the shunt falls out, Visger falls into a coma, so those with him have to follow the instructions on how to perform a kind of DIY brain surgery if they can't get him to a hospital:

It says, 'In the event of coma, with hospital not available' - this for someone else to do to me - feel for a reservoir the size of a nickel behind the right ear. Then there's a razor included, it says 'shave over the reservoir', there are benedine pads in it - scrub it for five minutes to sterilise it - and then there's a hypodermic that you can stick into the pump of the shunt to allow spinal fluid drip out for several minutes. If that doesn't work, there's another, bigger hypodermic - this is only if I'm dying - you can go through one of the holes in my skull, and suck it out. I tell people I prefer them not to do that, as they might suck out some of the white stuff, which still works.

As troubling as all of this is, Visger is most haunted by how the 49ers dealt with the first injury.

I'm in intensive care for 14 days at Stanford which is 40 minutes from our HQ if I remember correctly, and not a single person from the entire organisation came to see me, other than my two roommates, and they cut both before I got out of hospital. Terry Tautolo and Scott Stauch. One day a woman came in talking to me like we were best friends, and I had to ask 'who in the hell are you?'. She says 'I'm Bill's secretary'. Now I wasn't used to calling coaches by their first name, and I go - I was 22 years old - 'Bill? Bill who?' She says Bill Walsh, your coach, remember? So I said 'Yeah, I f***ing remember my coach'.

But she was the only person from the entire organisation. Not even my position coach came to see me. The niners knew they screwed up on my diagnosis, they knew they damned near killed me, and they didn't want anyone to be seen at the neurosurgery ward at Stanford because they knew people would ask questions. So while I’m in intensive care for 14 days, the trainers and doctors are calling me to tell me 'Hey, we're looking at getting a special-made helmet to protect your shunt so you can keep playing'. You gotta understand the mindset of athletes at that level, they will do whatever it takes to play. So if a professional tells me I can play, I'm going to frickin' play. So I come back after my brain surgery, Terry and Scott are gone, I'm working out every day trying to get back into shape to play.

[When I return to the 49ers] I walk in the locker room with my head shaved and 15 staples in the back of my head and they're asking ''Vis, what happened to you?' Well I had brain surgery. Even to this day some of my teammates don't know. So during the season, I'm working to get fit again, but they are treating my weird. Even when I hurt my knee, that's in the paper the next day. Here I am with brain surgery, nothing is being said, we're on a roll, kicking butt, winning and winning, and I'm wondering, 'What are they covering up?’

The 49ers took George Visger's dream and didn't let it mature half as much as they let it rot, contemptibly.

Those dreams have changed.

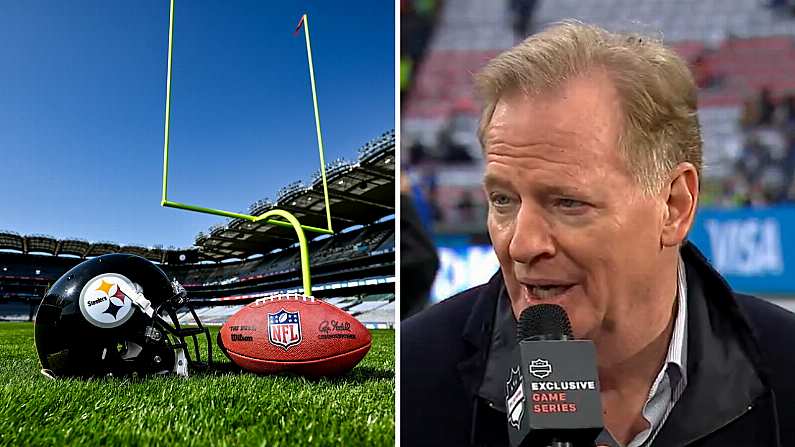

Everything is falling apart while I'm fighting this. I never see my kids, and my wife is saying 'Well, oh, he is always angry'. Well fuck yeah, I'm angry, who wouldn’t be? Who the hell in my shoes wouldn't be frickin' angry!? I used to dream, for years and years, of going back to the 49ers and beating the living shit out of Walsh, and now it's Goodell that's my target. Roger Goodell. I'd love to get him in a little room one day, in a one-on-one and get to talk to him. Yeah, I'm angry.

*****

The 49ers treated Visger as they did because they were allowed to. Visger pithily describes the NFL's attitude towards him and the thousands of retired players suffering with the sport's revenge on those who cared too much and worked too hard:

Us old players have a saying that the NFL live by: 'Delay, Deny, and Hope they Die.

The NFL formally began reviewing the long-term effects of concussion in football in 1994. It took them until December 20, 2009, to openly acknowledge it.

Those 15 years was marked by an NFL committee with little credibility denying and downplaying the true impact of football collisions while nearly a dozen former players committed suicide. All who were tested, tested positive for CTE.

Let's start with the issue of credibility.

In 1994, then-commissioner Paul Tagliabue agreed to the formation of the Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI) Committee - its goal was to investigate the long-term effects of concussion. Questions were raised about the chair appointed by Tagliabue: Dr. Elliot Pellman.

Pellman was working as a team doctor with the New York Jets and is a qualified rheumatologist, rather than a neurologist. He wasn't entirely honest about those qualifications, either: in 2005 it emerged that he had failed to disclose that he had received part of his formal medical training in Guadalajara, Mexico.

He was not redeemed by the quality of his committee's work. In 2003, after a six-year study of tackles leading to concussions, the committee found that a return to play after a concussion “does not offer a significant risk of a second injury” either in the same game or that season. This was quite revolutionary work by the MTBI Committee, given that Second Impact Syndrome was first identified in 1973, by R.C. Schneider.

Pellman believed what he had published: he once personally sent a concussed Wayne Chrebet of the Jets back onto the field soon after he had been knocked unconscious by a hit, reportedly telling him, “This is very important for your career".

Awkwardly for Pellman and co., they were met by a raft of studies contradicting their work. A NCAA study of the same year found that – having studied 2,905 college football players – those who suffered concussions were more susceptible to further head trauma in the next seven to ten days.

The same year, the Centre for Retired Athletes of the University of North Carolina found connections between concussions and depression in retired NFL players.

In 2007, Robert Cantu of the American College of Sports Medicine noted bias in the committee's extremely small sample size and held that no conclusions should be drawn from the NFL's studies.

And then, in 2013, the New York Times revealed that Pellman had served as Tagliabue's personal physician for years prior to his appointment.

What with all of these damaging reports flying around, the NFL decided to issue a couple of their own.

What the NFL promised to be the "definitive" study was to be conducted at the University of Michigan but led by Dr. Ira Casson, also a member of the NFL's MTBI Committee. Dr. Casson earned the nickname Dr. No among his profession, so often did he issue denials about the links between head injuries in the NFL and dementia, depression and short-term memory loss.

It began in 2007 (by now Roger Goodell had taken over as the league's commissioner) but this study was utterly undermined by the way the NFL went about conducting it. Independent experts said that the study was dogged by a conflict of interest: it was financed by the NFL, and Casson was performing every single neurological test, having already discredited evidence linking football to cognitive decline and dementia in retired players.

The statistical sampling was criticised too. The design of the study was to examine 120 NFL players in relation to 60 men who played only through college, spread across ages from 30 to 60. This, as the Democrat senator Linda Sanchez put it in Congress, was like "comparing two-pack-a-day smokers with one-pack-a-day smokers to see what the differences are,” she said, “instead of two-pack-a-day smokers with the general population".

She said this at a Congressional hearing in October 2009, at which Goodell and the MTBI Committee were asked to answer charges relating to neglect. Goodell was told by Sanchez that the NFL's constant denial of the long-term effects of concussion "sort of reminds me of the tobacco companies pre-’90s when they kept saying, ‘Oh, there’s no link between smoking and damage to your health". Goodell wasn't particularly helpful, with Sanchez remarking in an interview after the hearing that "really vague on certain things and didn’t know the answers to certain things".

But at least Goodell had the grace to turn up: something that could not be said of Pellman and Casson. The latter was asked to attend and was a no-show, with Sanchez saying that his studies should be discarded as he was "impartial from the outset". As this hearing was taking place, and the NFL's obfuscation and denial was clear for all to see, NFL players were given a pamphlet by the league.

It read:

Research is currently underway to determine if there are any long-term effects of concussion in N.F.L. athletes.

That appearance before Congress, along with mounting pressure from the NFL players' union, led to the NFL overhauling their concussion protocols in November 2009. And finally, the following month, official acknowledgment came.

The Casson-led study was paused, and while discussing an NFL donation of $1 million to Boston University for research into CTE, the degenerative brain condition linked to repeated head trauma, NFL spokesperson Greg Aiello said in a phone interview that "It’s quite obvious from the medical research that’s been done that concussions can lead to long-term problems".

15 years. The lawsuits followed just over two years later.

*****

George Visger was the 23rd former player named in the original lawsuit attorney Jason Luckasevic filed against the NFL in 2012, but by then he was a veteran of the courtroom. He had a five-year battle with the San Francisco 49ers to get compensation for his early brain surgeries, along with rehab for his knee: he busted his ACL with the 49ers, too. He won, was given just $10,552.50, but it was also ruled that Travelers insurance (on behalf of the 49ers) "provide such further medical care as is necessary to cure or relieve from effects of his industrial injury".

They were reluctant to pay the bills. In 2012, he met with representatives from Travelers' to settle for his knee and brain case. They offered $73,000 dollars, and $1100 a month for 15 years in disability allowance, guaranteed even if he was dead. In return, Visger would have to pay for every brain surgery, knee surgery and seizure tablet. He declined.

After an MRI scan showed signs of cortical atrophy (essentially the wasting away of parts of the brain), the insurance company hand-picked a nurse care manager to assess Visger, to determine the level of care he needed. After it was confirmed that Visger would need an intensive brain injury treatment, Travelers' asked the nurse to bury the report. Visger would then fight his way through the courts for five years to get Travelers to pay for his treatment, finally beginning treatment on May 30th of last year, 35 years after his first brain injury. These court cases were fought as his business imploded, as he was made homeless and as his marriage dissolved.

The battle is still ongoing: after the initial 30 days, it was agreed that Visger needed another four to six months of treatment. Travelers stopped paying the bills 27 days into the second month of treatment, and last November, a judge ruled that Travelers should pay for a further 90 days of in-house treatment.

Now he wants the NFL to pay.

“Here's the thing, taxpayers are paying for my problems now as I had to go out on Social Security disability when the NFL should be paying for it. Their insurance should be paying for it. I'm in another lawsuit with them to get my bills paid. I'm sick of lawsuits fighting to access my earned benefits. I just want my life back.”

“All I want to see is the NFL pay their bills. If they owe guys: pay it. When I had my own little business, I paid for work comp. If someone was injured, that was on me. That is standard. If I worked for K-Mart and had brain surgery, I'd have benefits. But not with a $14 billion industry? It's just...it's just ridiculous.”

******

On the face of it, Visger is getting his wish: the NFL are paying. In August 2013, it was settled that the NFL would contribute $765 million to provide medical help to more than 18,000 former players. The agreement also said that it should not be interpreted as a statement of legal liability on the part of the NFL.

While it seems like a substantial amount, and it may yet reach a billion dollars, the breakdown of the money is heavily caveated.

Neuro-cognitive impairment pays up to $2 million.

A five-year career in the NFL is necessary to qualify for a full payment: the average career is 3.2 years. Visger had a two-year career, but having brain surgery in one of those years discounts that. Further to that, a retired player must be diagnosed with that impairment by the age of 45 to qualify for their full payment. Visger was 56 at the time of settlement, meaning he is in the age bracket of 55-60, who are entitled to 40% of the payment. Thus, the $2,000,000 shrinks to $240,000.

Visger estimates he has lost out on millions in the last 36 years, from medical bills to promotions he couldn't take as a field biologist, knowing that his memory means he could not deal with the added responsibility.

In 2015, Roger Goodell took a $10 million pay cut. He still made $34 million. George Visger survives on $1,790 in disability allowance a month, along with an extra couple of hundred dollars here and there as payment for giving talks on Traumatic Brain Injuries.

In his first nine years as NFL commissioner, Roger Goodell made $180 million in salary. Several years ago George Visger wrote a lengthy obituary in a local paper for his brother.

It was sent back.

The paper charge by the word, and Visger couldn't afford it.

******

Amidst his daily struggle, Visger maintains a remarkable outlook, saying that he has been "blessed" to spend his life being paid for what he loved to do, be it work as a biologist, a live-in counsellor at a crisis intervention centre, and what he does now, brain injury consulting. He firmly believes that there's a purpose to all of this.

I think God's got a calling for me, and there's a reason I've gone through this crap. I truly believe that. I just hope I can hang in there long enough to get there.

In our first correspondence, he described himself to me as "the NFL's worst nightmare. A brain damaged defensive tackle with a biology degree AND integrity".

You know what, it's the truth. I get up, and I call them on their bullshit. I've played the game. And I've got a degree in biology, so I understand the physiology. And I've lived this shit for 38 years. Don't blow smoke up my ass and tell me about stuff. There is no one in this country that has the experience I've got. I've spoken, and the NFL knows it. they will try to dribble these little titbits to us, and I say screw you. Plus, I know the law, I've been through the legalese part of it.

For years they say 'George, you can't say those things about Goodell, they're going to sue you'. Fuck them. Excuse my language, I usually don't speak like this. But what are they going to sue me for? I don't have anything. I'm telling the truth. So bring it on. I speak the truth. I understand the injuries. I understand what they are doing. I understand how they taught us.

George Visger played in the NFL, but now he is fighting in what is really America's Game. And if the playing is ephemeral, the fighting is anything but.