Originally published September 18th, 2014

The immediate things that strike one about Balgaddy are the litter and the pylons. The twin adornments of that estate near Clondalkin.

The houses - built by GAMA construction, better known for their enlightened treatment of their Turkish employees - are ravaged by mould and beset by structural problems.

A three minute jaunt through the green at the heart of the estate is enough to convince anyone that the head of the local tidy towns committee needs to be impeached immediately.

Residents have long complained about the lack of adequate community facilities and the recent increase in anti-social behaviour.

Sinn Fein councillor Eoin O’Broin has even published a document outlining the many problems and hardships faced by the residents. It is entitled, ‘Balgaddy: A national scandal.’

But back in 1996, eight years before work commenced on these houses, this was envisioned to be the home of the Dublin Dons, aka the relocated Wimbledon FC.

A STADIUM FOR NEILSTOWN

In 1994, Cork property developer Owen O’Callaghan sought a meeting with Minister for Finance Bertie Ahern about his proposal to build a 60,000 seater national stadium at Neilstown.

He had acquired planning permission for the stadium the year before and envisioned that it would be used by Jack’s Republic of Ireland side, then flying high and ranked sixth in the world, but still renting the use of Lansdowne Road from the IRFU.

O’Callaghan had initially approached the Taoiseach Albert Reynolds to see whether the government would part-fund this venture. The gamey, affable Reynolds instinctively liked the idea but said it would need the approval of the Minister for Finance.

Showing both a disdain for the idea of splurging on a big national stadium and a fiscal prudence which would later desert him, Ahern clamped down on the idea at cabinet.

MURKY PRE-HISTORY

That the stadium idea was on the table at all was down to one of the murkiest decisions in the history of South Dublin County Council.

Neilstown was designated to be the home of a large and much needed town centre under the 1983 county plan.

However, things changed when Tom Gilmartin (Padriag Flynn’s unwell man) returned home from England, looking to develop a major centre at Quarryvale. After a couple of years trying to do this, things ran aground financially and AIB urged him to enter into a partnership with Owen O’Callaghan to bring the plan to fruition.

However, there were a couple of rather large snags. Under the 1983 county plan, Quarryvale had been designated as a ‘green-belt, residential area’.

The county manager also warned that the Quarryvale site was on the north-eastern periphery of the area and community it was meant to serve.

No matter.

O'Callaghan handed his primary lobbyist, Jack Lynch's former press secretary and future TV presenter, Frank Dunlop, £70,000 to help local councillors see the light on Quarryvale. Dunlop used this bursary to 'persuade' the likes of Colm McGrath, GV Wright and Theresa Ridge of the worth of rezoning the land.

With this large financial wind now backing the Quarryvale site, a motion to re-zone the land was tabled at South Dublin County Council in February 1991. You wouldn’t have needed to be Nate Silver to know which way this vote was going to go. The motion passed by 29-13.

The county plan of 1983 was completely torn up. Quarryvale was to be a residential area no longer. It could now house a shiny new shopping plaza. The Liffey Valley shopping centre opened there in 1998.

The dream of a centrally located town centre at Neilstown, serving the people of Lucan and Clondalkin, was now dead in the water.

What was to be done instead?

According to Frank Dunlop, the idea to substitute a football stadium in place of the absent town centre was a wheeze dreamt up by the one and only Mr. Liam Lawlor TD.

It was envisaged as a kind of ‘sweetner’ for the people of Neilstown, off-handedly tossed into the debate, as one might during a casual spitballing session.

Frank Dunlop flatly informed the tribunal that the idea was a ‘ruse’ designed to placate community leaders in Neilstown and enable the Quarryvale town centre plan to proceed unimpeded.

Ruse or not, Owen O’Callaghan became convinced it was a goer, especially after the accession of Albert Reynolds to the leadership of Fianna Fail. He wrote to FAI President Louis Kilcoyne outlining his plans to secure state support for the venture.

The idea, or ruse, survived until 1994, when Bertie Ahern insisted that there would be no public money for a national stadium at Neilstown.

DUNPHY

Some time in 1994, Joe Kinnear picked up the phone and called Eamon Dunphy. Wimbledon had just finished in the absurdly high spot of sixth in the Premier League. This was not a position reserved for teams with no ground and a tiny fanbase.

Dunphy and Kinnear were old friends from their days playing together for the Republic of Ireland side during the late 60s and early 70s, a period when Ireland barely won a match.

Despite possessing an accent that made him sound like a minor Only Fools and Horses character, Kinnear was in fact born in Dublin. This was something which was widely known and referred to in those days, much more so than it is now.

Kinnear told Dunphy that Wimbledon’s tennis loving Lebanese chairman Sam Hammam, invariably described as ‘colourful’ in newspaper reports, was looking to sell the club.

Then came a highly unorthodox suggestion. Would Dunphy be interested in helping the club upsticks and move the whole operation to Dublin?

I thought it was a great idea and I thought it was very doable because I thought Dublin could host a Premier League club and do so a lot more successfully than Wimbledon in South London.

Animated by the idea, Dunphy looked to get a consortium together to buy the club. He went to Paul McGuinness, the man behind U2, and two other friends of his in the music business, Tommy Higgins, the head of Ticketmaster in Ireland and Maurice Cassidy, the director of HMV here. The latter two Dunphy calls ‘football men’. McGuinness, most assuredly, was not a football man.

And he also went to Owen O’Callaghan.

Owen Callaghan had a stadium in Neilstown with planning permission. So I met him and he was very excited about it and very proactive about it and he effectively became the leading figure on our side of the project.

Architect Ambrose Kelly would design the stadium, envisaged to be either a 40,000, a 50,000 or even a 60,000 seater, depending on which report one read. Dunphy himself had no financial stake in the venture. For him, the idea of a Premiership club setting up shop in Ireland was ‘a dream.’

I didn’t have any money in it. I was doing it for entirely for altruistic reasons. I thought it was a dream for people not to have to send their kids away anymore… I think socially it would have been immense for Dublin. I think there was huge commercial benefits… imagine the revenue and employment generated if there were Premiership matches in Dublin, and maybe subsequently European champions League matches. It was a fantastically fruitful project for everybody.

He quickly became the public face of the scheme, going out to bat for it in television studios and radio programmes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JFf5yMuc-Ho

THERE’S NO DOWNSIDE HERE

Off-handed references were being made to the possibility of Wimbledon arriving in the media from 1995 onwards. However, it wasn’t until the early days of the 1996-97 season, that it reached the swanky press briefing stage.

A number of journalists were invited to a lunch in the Shelbourne Hotel in the autumn of ‘96. It was the first time members of the Irish media were given access to Sam Hammam. As a mark of how serious the organisers were about the project, a high-powered Belgian man by the name of Jean Louis Dupont was in attendance. Dupont was the lawyer who had represented Jean Marc Bosman in the seminal case of the previous year.

The consortium was justifiably confident that the Premier League had no problem with the move. However, they anticipated objections from the FAI and UEFA and Dupont’s presence was an obvious sign they were determined to surmount those. Dunphy, dropping some notable names, was confident the obstacles could be overcome.

The European commissioner at the time was Padraig Flynn and it came under his remit, and he was very friendly with Owen O’Callaghan, so we felt the European law allowed such a law that would trump any objection from UEFA.

The grouping was very quick to boast that they had all their ducks in a row. All problems collapsed in the face of Hammam and the consortium's airy nonchalance and their willingness to splash the cash around.

Probable objections from the League of Ireland clubs? The consortium would provide each League of Ireland club with €250,000 on arriving plus they would provide funds for the creation of schools of excellence which would be dotted strategically throughout the country.

Hooliganism? A very live issue, given that it was only 18 months since Combat 18 had thrashed the Upper West Stand in Lansdowne Road, the consortium insisted that the brand spanking new transport infrastructure that would accompany the building of the stadium would help prevent hooliganism. Also they insisted that a sophisticated security apparatus would be put in place to deal with any problems.

Wimbledon fans? The shark was well and truly jumped here when it was suggested that Wimbledon’s core fanbase could be flown over free of charge to watch the Dublin Dons in Clondalkin.

For those that cared, the anti-national obscenity of an Irish team playing in an English League wasn't even going to matter for long. There were a few things everybody knew in 1996 and one of them was European Super League was inevitable. To argue otherwise was to portray oneself naive and incapable of reading the writing on the wall. The consortium blithely insisted that the Dublin club, with all its money and potential would be there.

Journalists were split on the move. The ones regarded as sympathetic were regularly invited up to the then Chez Dunphy off Baggot Street, where he and O'Callaghan would brief them on how things were going. Dunphy was very confident about the prospect of Wimbledon arriving - to the point that he gave the impression that he knew something everyone else didn't.

Dublin's business oligarchs found the whole idea irresistible, with Tony O'Reilly taking it upon himself to meet FAI chief executive Bernard O'Byrne to try and persuade him of the merits of the proposal, while future Celtic owner Dermot Desmond was also rumoured to be in favour. The general view of the business community in Dublin was articulated by the Chamber of Commerce who announced that the arrival of Premier League soccer would bring huge benefits to the capital.

HAMMAM AND KINNEAR

Hammam spent much of the mid-90s whizzing in and out of Dublin. Watchful League of Ireland supporters regularly tipped off angry Wimbledon fans as to his presence in Dublin airport.

He was a flamboyant individual, one of those ‘character’ chairmen who proliferated in English football during the late 80s.

Whereas nowadays most Premier League chairmen resemble Bond villains, cosseted and aloof and, most of all, foreign, back in the 1990s, the majority were much more accessible, giving off that Thatcherite, self-made man-about-town vibe - reminiscent of the adversary in a Ken Loach movie.

Hammam provided a bridge between the two archetypes. The story goes that his chauffeur was driving him through London, animatedly talking about football, when Hammam threw out a line about always wanting to own a football club. The driver perked up and said ‘Why don’t you buy Wimbledon, they’re looking for investors.’

Often he could be seen sauntering along the touchline in his camelhair coat and scarf, getting sucked into back-and-forths with supporters, arguing with referees over decisions (as he did during a match against Manchester United in 1995), all the while charmingly oblivious to the fact that this wasn't considered normal behaviour for a Premier League chairman.

Kinnear was heavily praised for consistently over-performing as manager of Wimbledon. However, he spent most of the decade bellyaching about the fact that hadn’t any money to buy players.

Born in Dublin, before the family moved to Watford when he was aged seven, Kinnear came across as almost emotionally attached to the Neilstown idea, telling Bill O’Herlihy on RTE’s coverage of the Premiership that he had put his heart and soul into bringing the club to Ireland.

In the British media, he tended to be very curt, often simply noting of the idea that ‘it’d be brilliant.’ When confronted with the Irish media, he was much more forthcoming, claiming he had turned down offers from Celtic, Spurs and Man City because he what he wanted 'more than anything was to build a club in Dublin taking on the Manchester Uniteds of this world.' Kinnear promised to load the team with Irish players, saying that he had 'three already, Cunningham, Kennedy and Goodman and I'd look to buy more to emphasise the Irishness of the club.'

When the protests from Wimbledon supporters started ramping up, Kinnear was brutally blunt and unwilling to engage, casually dismissing them as a ‘bunch of idiots.’

Hammam was different.

Possessed of a slight hint of Boris Johnson like cheerful mischievousness and capable of the odd recklessly honest remark to the press, he admitted of the protests that he would ‘probably do the same thing’ if he was a fan.

But then, he paused and sighed;

Dublin is a fantastically sexy option, what else can I say?

‘BULLSHIT-SPORT’

One of Marc Jones’ big regrets is that he didn’t keep the letters. If he still has them, they’re in a dusty box somewhere and he can’t find them.

He wrote to every Premier League chairman. He wrote to the chair of the Premier League and the chair of the Football League. And he wrote to the FAI.

Along with a few others, he founded the Independent Wimbledon supporters club in 1995, largely to fend off Dublin and other similar schemes. And he was writing to the Premier League chairmen to request their support in blocking Hammam’s plans.

A couple of them wrote to them saying ‘knowing Sam as I do, I know that he’ll only do what’s best for the club. A couple of them wrote back saying I hope it gets defeated. Doug Ellis at Aston Villa basically said fuck off, what’s it got to do with you?

In those fractious days, the biggest chink of light for Wimbledon fans came from the FAI and those within Irish football.

The League of Ireland gave me the most hope out of all of it... I remember getting it and thinking ‘fucking hell, number one, they’ve written back’ and ‘number two, they’re telling it as it is’… they were the straightest talking people, they were the only ones saying ‘I think it's bad, I don’t think it's right, it's not what football’s about, you got all our backing... ’

Wimbledon fans had been on an almost permanent war footing since 1987. That year, Hammam, along with former chairman Ron Noades, had attempted to merge the club with Crystal Palace.

Four years later, they had vacated their Plough Lane ground following the 1990-91 season, and moved in with Palace at Selhurst Park - one of those temporary solutions that ends up lasting for about a decade.

The post-Hillsborough stadium legislation demanded that grounds upgrade to all-seater and Hammam took the opportunity to declare the necessary redevelopment impractical.

There were protests following their exile from Plough Lane but these quickly subsided. A dinky, ratchety little ground of the type one only sees now in FA Cup round-ups, Wimbledon fans had long dreamt of a return to their homeland.

Instead came talk of moves to salubrious hotspots like Gatwick and Basingstoke, and cities like Cardiff and Dublin. Of all the mooted switches, Dublin was the one that excited the higher-ups most. According to Jones, 'the whole thing was based around 'imagine how much fun it'd be to go to Dublin as an away fan.'

This being the pre-internet days, large protests were more difficult to organise. The Arab spring would never have taken off in quite the same way if it had been wholly reliant on leafleting.

No one had mobile phones, it was like meetings above pubs, walking around with photocopied flyers saying ‘Everyone get together on Saturday, we’re going to talk about the Dublin thing.

The biggest stand-off occurred after a 5-2 defeat to Manchester United in August 1997, when the home fans refused to budge from the stadium for up to two hours after the game, brandishing placards proclaiming ‘Dublin equals death’ while roaring ‘we’re never going to Dublin.’

Kinnear slinked away down the tunnel, refusing to engage with the ‘idiot’ supporters. Commendably, and with that little air of the showman, Hammam walked out amongst them, stopping to debate the issue every few yards. Perhaps as a tribute to the chairman’s charisma or the fans’ unspoken appreciation that he was coming out to engage with them, he wasn’t manhandled and roughed up at any stage.

In a further attempt to mollify the supporters, Hammam took Jones and five other leading protesters out to dinner at a Wimbledon restaurant.

It was a perfect case of keeping your enemies closer than your friends. He was saying to us ‘I’m the father of the club and like in any family, the father decides what’s best for the club and you lot can do what you want. I said to him ‘I’d fly from Dublin to England to watch Wimbledon play but I’m not doing it the other way.

For Jones, the viability of the venture was not the issue. Economics were beside the point.

I never ever argued against the economics of it. I never stood up and said ‘Nobody will watch it in Ireland. Nobody will want to go to Dublin to watch a football match. I never said that because I knew that was all true. Of course, people will go and watch it. But it doesn’t mean to say that it’s right.

They resolved that night that if the worst happened, they’d start a non-League club.

The Dublin thing proved to us as Wimbledon fans that it isn’t about whether you win the Premier League or the FA Cup again. It isn’t about how many people are watching you, it isn’t about how good your centre forward is and how much money you’ve got in the transfer market. What makes a football club is the area it's born from, the area that it represents. And if you take that away, it's not football anymore. It's baseball then, it's American football, it’s just a bullshit sport.

'THE DEATH OF THE LEAGUE OF IRELAND WITHIN FIVE YEARS'

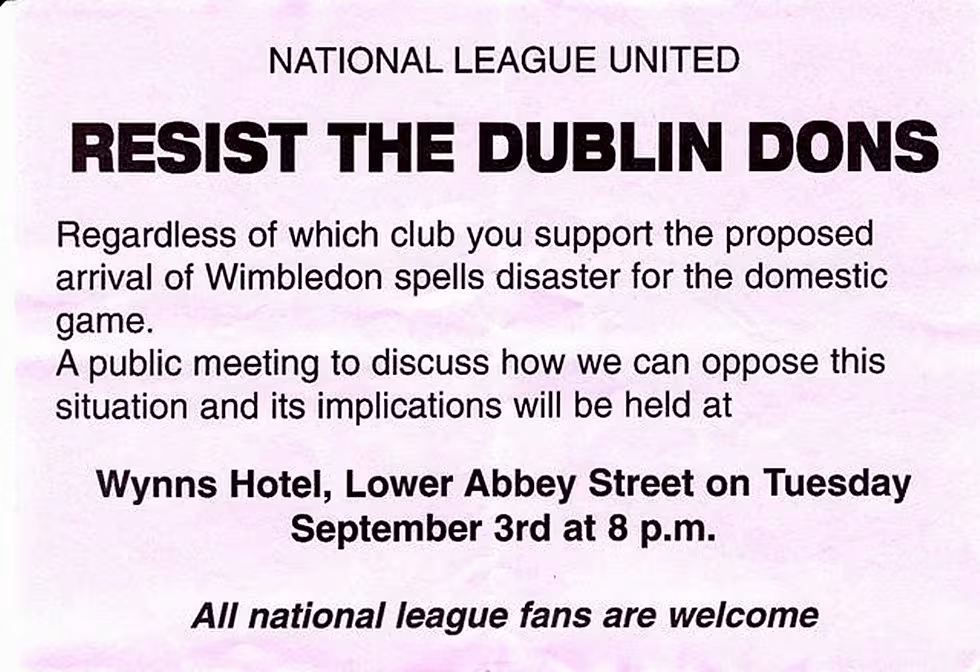

Some three hundred football supporters packed into a function room in Wynn’s Hotel in early September 1996.

The grouping, calling itself National League United met to discuss the apparently imminent intrusion of Wimbledon/Dublin Dons into the country’s football landscape.

Niall Fitzmaurice, the chairman of the Shelbourne supporters club, told those attending that the arrival of the ‘Wimbledon Dons’ would mean ‘the death of the National League within five years.’ He said the aims of those pushing the move were ‘purely financial’ and they ‘had no love for the game.’

It was the settled view of most supporters that the arrival of Wimbledon had the capacity to lay waste to the League of Ireland.

Irish people who didn’t go to League of Ireland games (that is to say, most Irish people) didn’t much care about this. Polls continually showed high support for the idea of a Premiership team landing in Dublin.

But among the faithful, there was great fear. As usual the League was in a bad place. The thinking was that if a 'monster like this arrived in their backyard, they would have no way of surviving whatsoever.'

Fitzmaurice reckons the ferocity of the feeling against the move in the League as a whole cowed anyone who might have thought about putting forward a differing opinion.

I think the feeling against the move was so strong within the League that there were very few people who were willing to voice a different opinion even if they held a different opinion.

Eamon Dunphy maintained that the Wimbledon project would bring a host of benefits to the League of Ireland.

A kind of trickle down economics effect would operate. He argued that league attendances would not be hurt because the presence of a Premiership club in the capital would develop a culture of going to football week in week out. His stock argument was that the presence of Manchester United in Lancashire doesn't stop people going to watch Rochdale, Bury and Oldham.

The centres of excellence would develop players, some of whom would go to England but many of whom would become good players in the League of Ireland. A host of professional footballers would settle in the country and could be groomed to become coaches in the League of Ireland later on. In addition, the move to summer soccer was already being openly considered by the League at the time, so the two entities would not even be in direct competition.

But League of Ireland people were not likely to be easily persuaded by anything Eamon Dunphy said.

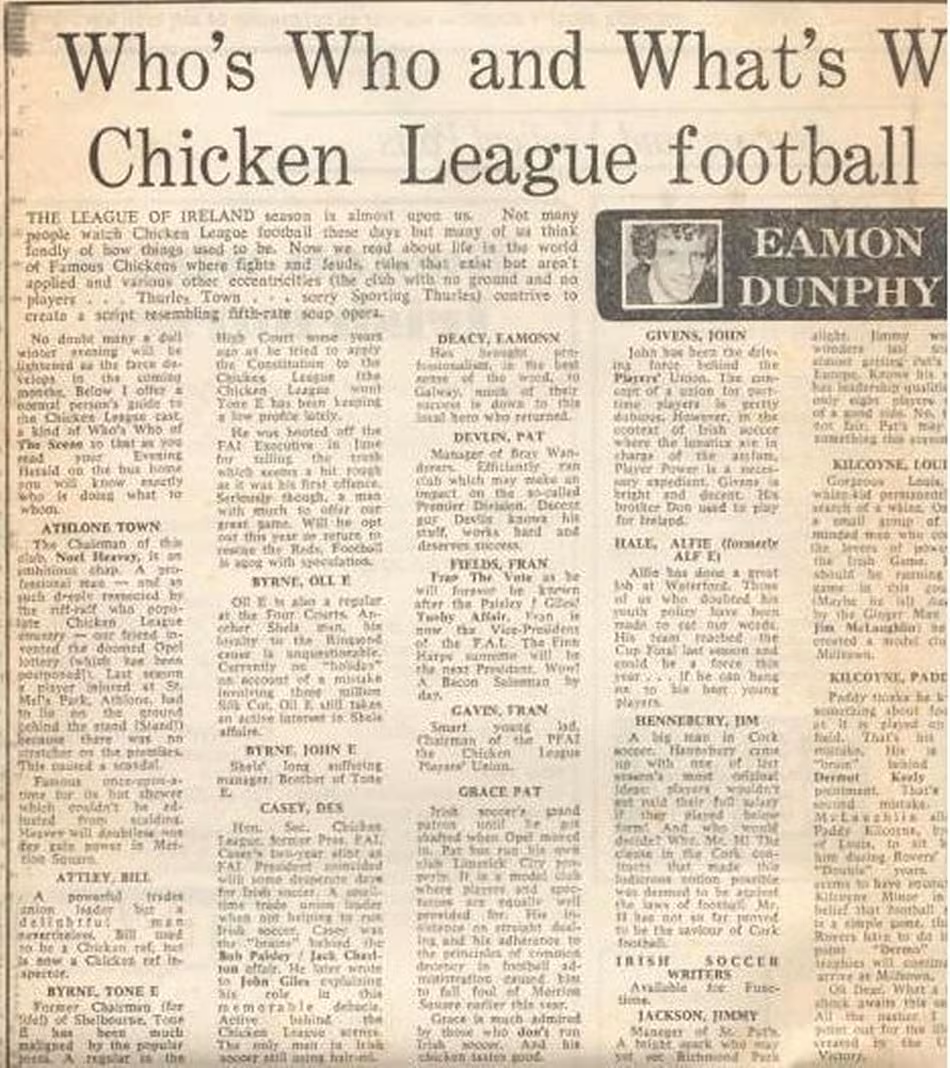

Dunphy's attitude to the League of Ireland had soured back in the late 70s, after his and John Giles' attempts to turn Shamrock Rovers into a club capable of competing in the European Cup had ended in demoralising failure.

As the Sunday Tribune’s soccer correspondent in the 1980s, Dunphy was lumped with the task of covering the League of Ireland, an undertaking he approached with an heroic level of insolence.

Every week, he mercilessly lampooned the ‘Chicken League’, so called on account of the League’s rather hickish sponsors at the time, Pat Grace’s chain of Fried Chicken fast food shops.

He reached out to Dr. Tony O’Neill, the director of Sport in UCD, former general secretary of the FAI and someone who was generally regarded as a font of wisdom within the association.

I spent a lot of time talking it through with Tony. He was in doubt, sometimes he was in favour, sometimes he saw the downside of it… He was a moderniser and he saw the vision.

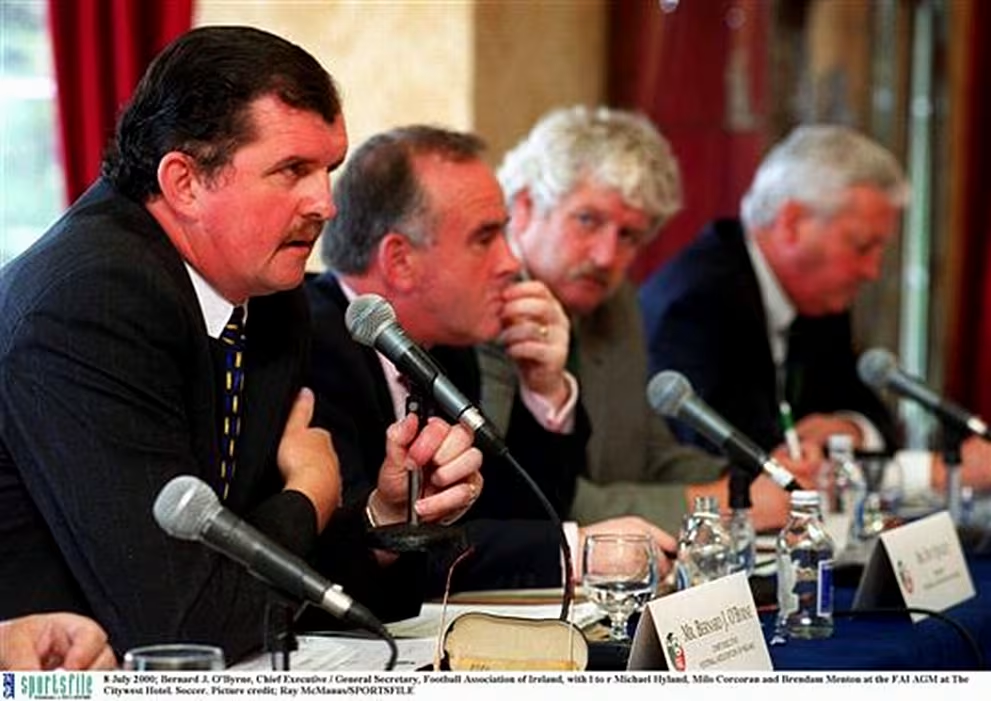

The then chief executive of the FAI, Bernard O'Byrne, most associated in the public mind with the attempt to bring Eircom Park to fruition, was a different story.

He indicated that whatever polls said, their own surveys of League of Ireland clubs revealed serious and concerned opposition.

His opposition was expressed in the kind of strident tones that would have delighted any Wimbledon fan at the time. In one interview with the English version of the Daily Mirror, the reporter noted that one could 'hear the flaming breath of a dragon snorting down the phone when the names Wimbledon and Sam Hammam are mentioned to him.'

He told the Daily Mirror man that 'the motivations (for the project) are the sort of greed that is enveloping football everywhere right now.'

Appearing on Liveline opposite Owen O'Callaghan in 1997, O'Byrne told presenter Marian Finnucane that the FAI 'weren't interested in Judas money', at which point O'Callaghan, firmly on the defensive, interjected meekly, saying that's 'very unfair'. O'Byrne ploughed on regardless.

Much like Marc Jones, he wrote a five page letter to the Premier League chairmen, outlining the association's objections to the move.

Not everyone within the League was dead against the plan. It had some enthusiasts but they weren't too numerous. Shelbourne’s manager, Damien Richardson, never shy with a contrary opinion, was one of the few League of Ireland figures to admit a liking for it. He was adamant that it would 'raise the profile of the sport in Ireland and the League would benefit.'

Fr. Joe Young, the chairman of Limerick City, was also up for the move but his club were against it. The lofty Hammam came down from on high and, accompanied by Owen O’Callaghan, met representatives from a number of clubs, including Athlone Town and Drogheda United, in an effort to get to drop their objections.

The attitude of most League of Ireland chairmen was typified by Mr. Shelbourne himself, Ollie Byrne, who lambasted the plan in a freewheeling interview with Hot Press in 2003.

If there’s to be a Dublin club in a future European Super League, it will come from within and benefit the existing league structure here. If Sam Hamaan and Joe Kinnear had come to us with a plan that worked in parallel with the Eircom League we’d have listened, but they showed total disregard for the people who’ve kept the professional game here alive. I’m not going to let somebody come in from England or Scotland and ride roughshod over what we’ve been doing as a league.

In the event, all 22 League of Ireland clubs voted down the plan to allow Wimbledon relocate to Dublin.

18 years later, Fitzmaurice, who is still on the board of Shelbourne, is inclined to doubt his earlier certainty on the issue. While not exactly performing a u-turn, he does concede the possibility that the arrival of Wimbledon could have helped football in the country.

In hindsight, you might look back and say, could it have maybe helped here, you know, get people going to football regularly, and maybe if the deal was done that they feed money down to the clubs and the League here, maybe it could have helped but nobody knows...

CLYDEBANK: 'BIZARRE' AND A 'JOKE'

Dublin was becoming a magnet for British football clubs. Around the time the Wimbledon plan was creaking badly, Scottish club Clydebank came out and announced that they too wished to move to Dublin.

UCD economist Colm McCarthy, better known for advising the government on their cost-cutting measures in the late 1980s (and again in 2009), held a 15% stake in the club. The club were losing money at a rate of £6,000 every week.

At a press conference in the RDS, McCarthy told the assembled that the club had reached an agreement with Royal Dublin Society to rent the ground for the following season. Shortly afterwards, a new ground would be developed nearby.

This is not a complicated idea. It makes sense for Scottish football, for Clydebank and it makes sense for Dublin. We aim to prove that a full-time professional team, based in Dublin, can be successful.

The Clydebank move generated less momentum than the Wimbledon one and was taken much less seriously. Bernard O'Byrne was both irritated and bemused by the proposal, describing it variously as a 'joke' and 'bizarre'. Either way, the Scottish FA never got behind the move and their former chairman Jack Steedman said he 'had more chance of winning Miss World than Clydebank had of moving to Dublin.'

Looking back, O'Byrne reckons the faintly surreal Clydebank proposal only served to bring the concept of moving clubs around willy nilly into disrepute. It was a scheme that could almost have been dreamt up by Wimbledon fans.

My memory now is that it was a ten-day wonder and did more damage to the Wimbledon argument than anything else because it was so silly.

THE SPRAT TO CATCH A MACKEREL

Eamon Dunphy laughs wearily when asked when it dawned on him that the dream wasn't going to come true.

Well in my case, three years... I spent three years on it which turned out to be a terrible waste of time. I could have written books and done all kind of things...

After three years of protests and objections and roadblocks, the plan was pretty much dead by the time the 1998 World Cup rolled around.

FIFA's position on the issue was a masterpiece of fence sitting and was thus spun every which way in the local media by both sides of the argument. Essentially, they allowed the FAI make the call. Interestingly, while it was the FAI's hostility that eventually did for the plan, in Dunphy's eyes, one of the big problems was actually the man at the centre of it.

The problem person was Hammam, to some extent. We weren’t sure how genuine his offer was. In the end, he kept putting the price up.

Hammam, a dilettante to his very core, kept on flipping over and back on the idea, occasionally being very gung-ho for it (particularly when he was in Dublin) and occasionally pulling back and insisting that the club should absolutely remain in Wimbledon (usually when the time came to pen his programme notes to supporters). In hindsight, Dunphy suspects that Hammam used the Dublin Dons plan as a ruse to draw in a bigger buyer.

The whole tailed off when he found a couple of Norwegians, they were shipping magnates and he sold Wimbledon to them for £70 million (reports vary on price) In the back of his mind, he was looking for us to get someone else, we were the sprat to catch a mackerel

However, the arrival of the Norwegians, named Bjorn Rune Gjelsten and Kjell Inge Rokke (though they were only ever known as 'the Norwegians') on the scene did not kill the Dublin Dons. Indeed, the promise of Dublin was one of the principal reasons they got involved.

Asked to instance the one person in a senior position he felt most hostile to the idea, Dunphy pauses and reaches around for the name.

- Was it that fuckin' O'Driscoll? Was he the head of it (FAI)?

- Bernard O'Byrne?

- Bernard O'Byrne, yeah. Yeah, he would have been the fly in the fuckin' ointment.

Despite his reputation as an implacable opponent of the scheme, O’Byrne, who now heads up Basketball Ireland, insists he would have been open to the venture had the consortium gone a different way about promoting it.

In O'Byrne's estimation, the consortium's alleged mixture of bravado and casual arrogance in their dealings with the FAI alienated officials and indicated to the chief executive that they didn't have the best interests of Irish football at heart.

He also suggests that Hammam and Kinnear probably came to regret the media people they linked up with to promote the idea. The name of Dunphy looms large in the background here in bright neon lettering. The pair's relationship seemed strained at the time but O'Byrne maintains that relations are good now.

O'Byrne says the FAI's opposition was pivotal in blocking the idea, insisting that FIFA may have sanctioned it had they laid out the welcome mat.

We told FIFA that ‘we believe it's bad for our football, they don't have the best interests of Irish football at heart, and we want you to block it.'

The whole thing just kind of 'tailed off' is a perfect description of what happened to the Dublin Dons project.

The backers of the proposal, though disappointed, moved on and found other hobbies to occupy their time. The League of Ireland continued on its way, switching to summer soccer in the early 2000's, and enjoying a brief period of modest success in European competitions in the mid-2000s.

Eventually, Wimbledon did move (or rather their league position was successfully flogged off) to Milton Keynes (without wanting to be too chauvinistic about it, a decidedly less sexy option than Dublin) a soulless town 45 miles north of London which didn't exist before the 1960s.

Those Wimbledon fans who established the Independent Wimbledon supporters association in 1995, Marc Jones, Lee Williet, Xavier Higgins, Kris Stewart and Laurence Lowne, immediately enacted their 'emergency break glass' plan and founded a new club.

AFC Wimbledon played their first match in the Combined Counties League in 2002 (incidentally, the club's first ever goal was scored by Glenn Mulcaire, part-time footballer but now better known as the News of the World's go-to-hacking expert). In 2011, they reached the Football League after beating Luton Town in a penalty shoot-out.

Returning to that fateful meal in Wimbledon in 1996, Hammam asked Jones and the other protesters what they’d do if Dublin went ahead.

I said to him sitting in the restaurant in Wimbledon, ‘we’d start another football club in Wimbledon. We’d start again. Which would be a non-league side.’ And his reply was, ‘If you did that, I’d pay to set it up.’ We all know that that’s what we did. We’re still waiting for him to pay up.